Close your eyes and try to picture Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia marching north through Virginia and Maryland 159 years ago today. Their lines of march would have stretched for miles. If you are like most people you are probably picturing an army of white men. But in this army of roughly 75,000 men there were thousands of enslaved men were forced to assume a wide range of roles that made it possible for the army to march, camp, and fight.

Now jump ahead to the afternoon of July 3, 1863. Picture Confederates falling back from having briefly penetrated Union lines along Cemetery Ridge. Some of you may even be imagining Robert E. Lee, riding out to meet what was left of the Pickett-Pettigrew assault, and declaring that ‘it has all been my fault.’ I suspect few, if any, of you are imagining the hundreds of enslaved men who emerged from Spangler Woods and other positions along Seminary Ridge to lend assistance to these wounded and defeated men.1

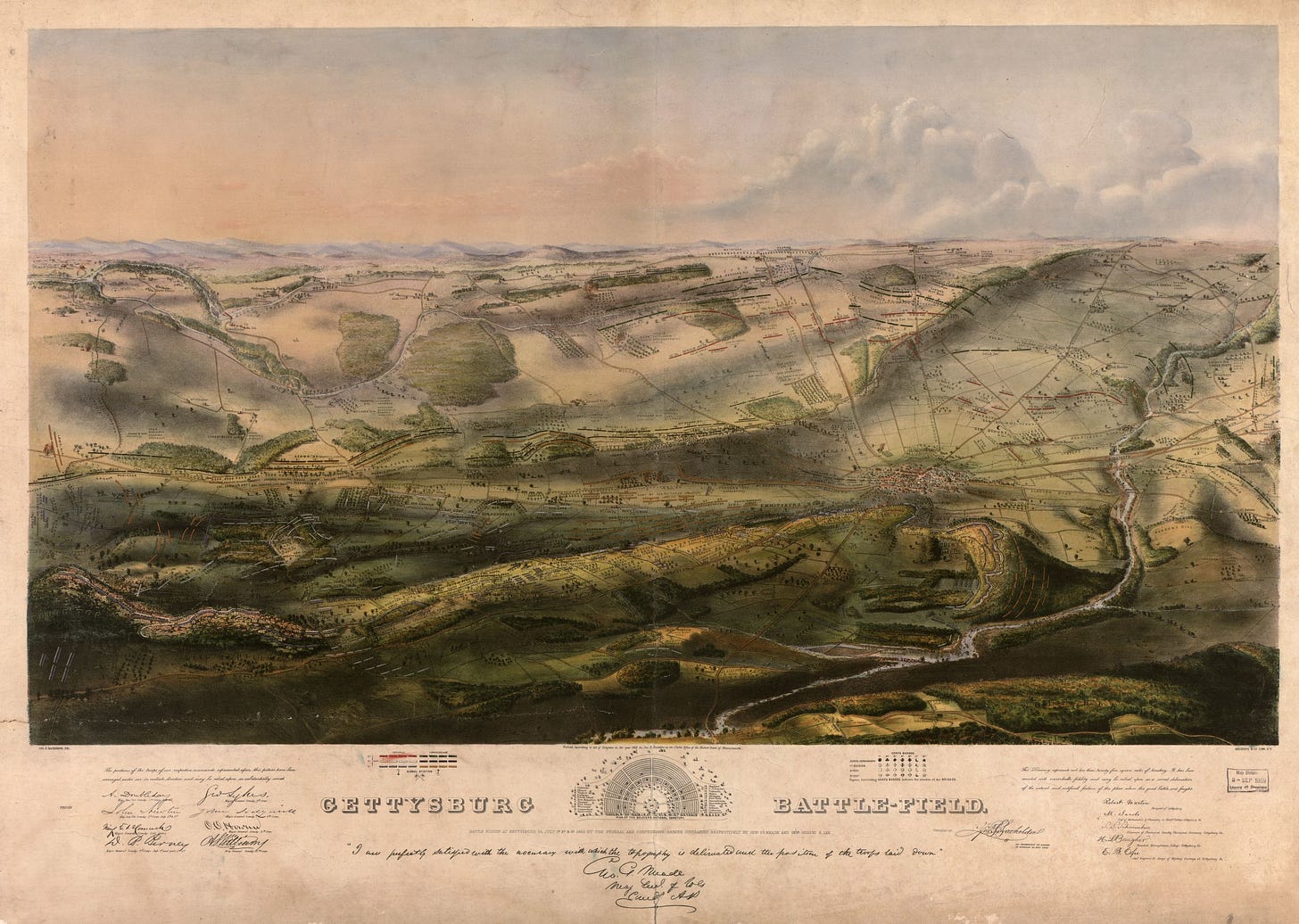

Thousands of books have been written about the Gettysburg Campaign. Massive tomes have been written about individual days, even specific engagements such as the fight at the Peach Orchard, the Railroad Cut, Devil’s Den, and Little Round Top. You can follow individual regiments through the 3-day fight and read countless biographies about privates all the way up to the commanding generals themselves.

We now have administrative histories covering how the battlefield has been maintained and interpreted over time as well as thoughtful studies that focus on the memory of the battle. The civilian experience has also enjoyed considerable attention in recent years.

Thankfully, we also now have some excellent studies that focus on the African-American experience, including the Confederate kidnapping of free Blacks during the initial phase of the invasion of Pennsylvania.

What we don’t have is a study of the role of enslaved men in the Confederate army during the campaign. I’ve been thinking about this over the past few days. I touched on this subject very briefly in Searching for Black Confederates, but next summer I will be co-leading a tour with Peter Carmichael and Jill Titus on the role of enslaved men at Gettysburg for the Civil War Institute.

Most of what I cover in the book focuses on the presence of body servants or what I call camp slaves, but this only scratches the surface of where these men could be found on the battlefield and their responsibilities throughout the campaign.

There may have been as many as 10,000 enslaved men with Lee’s army that summer. They are vital to understanding how the army functioned as well as the ebb and flow of battle.

We do know something about these men beyond my own book. Joseph Glatthaar includes a chapter about enslaved labor in his study of the Army of Northern Virginia and Larry Daniel does something along the same lines in his fine book about the Army of Tennessee.

One of the most important books that sheds light on this subject is Kent Masterson Brown’s Retreat from Gettysburg, which I heavily relied on for my own book. Brown deftly explores the ways in which enslaved men assisted the army in its march back to Virginia as well as the steps that many took to embrace their own freedom by running away.

Something along the lines of what Brown did for Lee’s retreat needs to be done for the entire campaign, but not simply to dig even deeper into the minutiae of battle/campaign history, but to offer a new way to think about this battle and to expand the scope of Civil War military history.

I share the concerns of some people. I mean, do we really need another Gettysburg book?

There are much larger issues to be explored beyond trying to better understand how enslaved labor was utilized by the army.

Here is a moment during the war in which a Confederate army brought the institution of slavery into a free state in the summer of 1863. That fact alone can help us to better appreciate what was at stake in the third year of the war, months after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

The institution of slavery itself was on the march.

I’ve long been troubled by our tendency to keep slavery at arms length in battle/campaign studies. Historians now regularly acknowledge it in the bigger picture. Accounts of armies confronting slavery and the enslaved in various ways has been explored, but acknowledging the presence of enslaved men in the Confederate army itself places it closer to the center of the action.

We now have a deep body of scholarly studies of soldier ideology and the importance of slavery as a motivation to fight. I think this discussion has largely been played out, but we still know next to nothing about how the rank-and-file experienced slavery in the army.

In other words, I am now less interested in whether Confederate soldiers fought to preserve slavery than I am in the ways that they were confronted by enslaved men. Where did Confederates see these men in camp, on the march, and in battle? Looking at it from this perspective it is undeniable that—reglardless of whether they owned slaves—Confederates understood that the insitution constituted the “cornerstone” of the army.

I also want to know more about how the enslaved experienced the battle and campaign and the ‘world they made’ while in the army. What specific roles did they play beyond body servants? Where would they have congregated during the 3-day battle. What did they see? How did they view this unfolding drama? These are incredibly difficult questions to answer given the available source material, but perhaps we can catch a fleeting glimpse.

Finally, I see this project as assisting the National Park Service in its ongoing efforts to interpret the Gettysburg battlefield, especially at a time when the war and its legacy is front and center in our national discourse.

No issue has proven more divisive in recent years than the park’s Confederate monuments, all of which loom large over much of the battlefield along Confederate Avenue. I would love to see wayside markers and especially tours that help visitors understand the great gulf between the Lost Cause memory that these monuments continue to reinforce and the history of slavery that they were intended to minimize and ultimately erase.

What better place to talk about the Army of Northern Virginia as an army of slaves than at the Virginia and North Carolina monuments.

For now I am only thinking about this in preparation for next summer’s battlefied tour, but I definitely see a book in all of this as well. Whether I am the right person to write it is not at all clear.

First things first. I am hoping to finish my biography of Robert Gould Shaw by the end of the year. After that I am committed to writing a chapter for a collection of essays on recent debates surrounding Civil War memory. My next book project is a co-authored short history of Boston during the Civil War. The book will be structured around artifacts from the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society and local sites in the Greater Boston Area. Somewhere in all of this I need to finish editing the wartime letters of Captain John Christopher Winsmith as well as his correspondence and speeches during Reconstruction.

You get the picture.

Thanks to Peter Carmichael for pointing this out to me.

I think we'll be well served with just one more Gettysburg book. Please let us know when you'll be leading tours. Thanks!

This reminds me of a couple things I've read recently. Perhaps you've heard of "The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America" (2019) by Khalil Gibran Muhammad? In his second chapter, 'Writing Crime Into Race: Racial Criminalization and the Dawn of Jim Crow" he explores how an early sociologist who wrote foundational texts on criminality could look at poor Irish and Scottish people committing crimes and say "This is because of poverty" and look at poor Black people and say "This is because they're Black." Not just that, though, this author was challenged by a prison doctor named M. V. Ball that actually you could make the poverty case for both groups. He forced the other researcher to face that racist thinking. Unfortunately, the other author insisted on being blind to it and rationalizing it away.

Another book I've been reading lately (my apologies for the longer post) may be of great interest to you. It's called "The Racial Contract" by Charles W. Mills (2nd edition - 2021). He's exploring how political theory does not address reality for most people (which is that Western society is founded on White Supremacy). The racial contract is in juxtaposition from the social contract. The social contract is an ideal that doesn't exist (that individuals come together to shape society for a general betterment of all). Instead, it's a racial contract, where White people have come together to agree to mutual benefit at the exclusion of non-Whites.

What is most relevant to you perhaps is Mills' theory of the 'epistemology of ignorance'. Which is a process of turning away, averting their eyes, and rationalizing difference to justify discrimination and racism against another group. It's a fascinating theory that has helped me grapple with how society often responds to racial injustice. I'll end with a long quote:

"But for the racial Contract things are necessarily more complicated. The requirements of 'objective' cognition, factual and moral, in a racial polity are in a sense more demanding in that officially sanctioned reality is divergent from actual reality. So here, it could be said, one has an agreement to misinterpret the world. One has to learn to see the world wrongly, but with the assurance that this set of mistaken perceptions will be validated by white epistemic authority, whether religious or secular.

"Thus in effect, on matters related to race, the Racial Contract prescribes for its signatories an inverted epistemology, an epistemology of ignorance, a particular pattern of localized and global cognitive dysfunction (which are psychologically and socially functional), producing the ironic outcome that whites will in general be unable to understand the world they themselves have made." (p. 60)

That seems to get at a bit of what you're talking about - when faced with these things, what do they wrap themselves in to justify ongoing slavery? Perhaps an epistemology of ignorance.