Three Martyrs to the Union/Abolitionist Cause

Read to the end and help me out by answering a very simple question.

I am currently working away at writing the Introduction for my biography of Robert Gould Shaw. I’ve been playing around with the idea that there were three martyrs to the Union/abolitionist cause between 1861 and 1865, each of them occupying a unique place along the timeline.

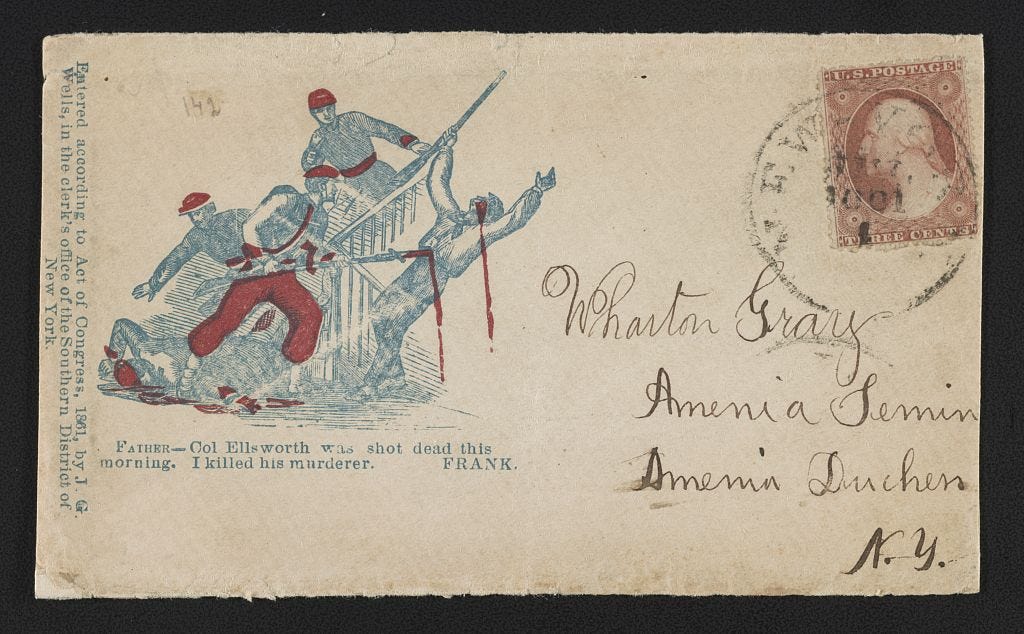

The first is Col Elmer Ellsworth, who was killed while attempting to remove a Confederate flag from atop the Marshall House in Alexandria, Virginia on May 24, 1861.

Ellsworth made a name for himself by leading a number of militia units in the 1850s, in places like Chicago, Milwaukee, and Madison before moving to New York to organize the 11th New York Infantry Regiment (or “Fire Zouaves”).

In 1860, Ellsworth traveled to Springfield, Illinois to study law under the future president, becoming fast friends with the entire family.

Ellsworth and the 11th New York rushed to Washington after the firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers. His death so early in the war and in such a symbolic gesture was a devastating blow to Lincoln and his family. An honor guard escorted Ellsworth’s body to the White House, where it lay in state in the East Room.

The phrase "Remember Ellsworth" became a rallying cry and call to arms for the nation.

[Looking for a good book about Ellsworth? Check out the late Meg Groehling’s biography First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North First Civil War Hero.]

The final martyr to the Union/abolitionist cause, of course, is President Abraham Lincoln, who was felled by an assassin’s bullet on the evening of April 14, 1865 at Ford’s Theatre, just a few blocks from the White House.

The story of Lincoln’s ascension to martyrdom is ably told by historian Martha Hodes in her book Mourning Lincoln.

Falling midway between the deaths of Ellsworth and Lincoln is that of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who was killed while leading the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts in battle on Morris Island on July 18, 1863. His death occurred midway through the war, just a few weeks after United States victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg.

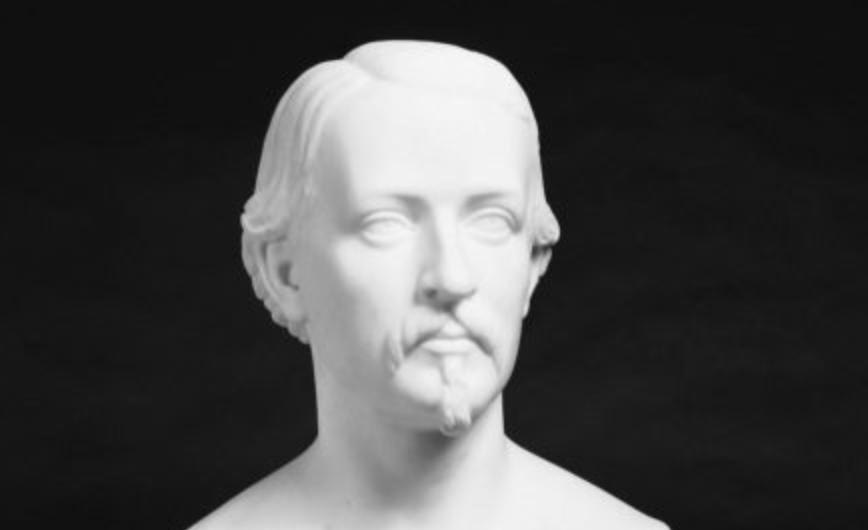

Like Lincoln, his rise to martyrdom also occurred immediately in the weeks and months after his death owing to the efforts of his family, the abolitionist community, the men of the Fifty-fourth, and Black Bostonians like Edmonia Lewis, who created a bust of the slain colonel for a fair in 1864. I explore all of this in the final chapter and epilogue of my book.

Shaw remained a touchstone of an “emancipationist” memory of the war for decades after the war, culminating in the dedication of the Shaw Memorial in Boston in 1897.

African Americans remembered Shaw, in connection to the Fifty-fourth, throughout the twentieth century, especially during the civil rights era, but the nation was reminded of his brief life and service through the Academy Award winning movie Glory, which premiered in 1989.

Of the three individuals listed above, only Lincoln and Shaw are remembered today, with the latter admittedly at a far distant second. Even so, I am left with a very straightforward question that I would like some help with.

Is there anyone, below the rank of general in the United States army during the Civil War, who is more popular or recognizable than Robert Gould Shaw?

[Please note that I am not asking for students of the Civil War or Civil War “buffs” but among the general public.]

Thank you.

(Now that I've scanned the contributions to see if someone beat me to suggesting:)

...sorry, my candidate lived to the same year Bobby Lee did, 1870. He was the first Admiral in the USN, which made him the first Latino admiral. His dad, Jordi Farragut Mesquida, was a Latino immigrant who liked the USA so much he Anglicized his name.

He might have been martyred if one of those torpedoes had damned him in Mobile Bay. I'll wait eagerly for the next contest.

Robert Anderson perhaps? But I doubt anyone really remembers him, they just remember that For Sumter was the start of the war.

Clara Barton comes to mind, if you stretch your definition of military service to those civilians who served in roles that would today be part of the military.