There Is No Better Place to Honor John Lewis Than On the Spot Where a Confederate Monument Once Stood

When asked why he was so passionate about calling for the removal of Confederate symbols from federal property in 2020, following the police murder of George Floyd, Georgia Congressman John Lewis stated: “It represents the dark past as a symbol of separation. A symbol of division, a symbol of hate.”

He recalled that a number of Alabama state troopers who beat him and other protesters, as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on “Bloody Sunday” on March 7, 1965, had Confederate flags painted on their helmets.

The patrol cars of Alabama state troopers were outfitted with Confederate flags in the position of the front bumper.

A few weeks later and under federal protection, hundreds of civil rights marchers set out once again from Selma and walked to Montgomery to demand voting rights. On their way they passed white Alabamians, who flew the Confederate flag in protest.

Those state troopers and residents understood the meaning of the Confederate flag as did Lewis and his fellow freedom fighters.

It is fitting that today a statue honoring John Lewis is being dedicated in DeKalb County, Georgia, on the same spot where a Confederate monument once stood.

The unveiling of the Confederate monument took place in 1908, at the height of monument dedications during the Jim Crow era. DeKalb’s monument was installed two years after the Atlanta Race Massacre and seven years before the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan on nearby Stone Mountain.

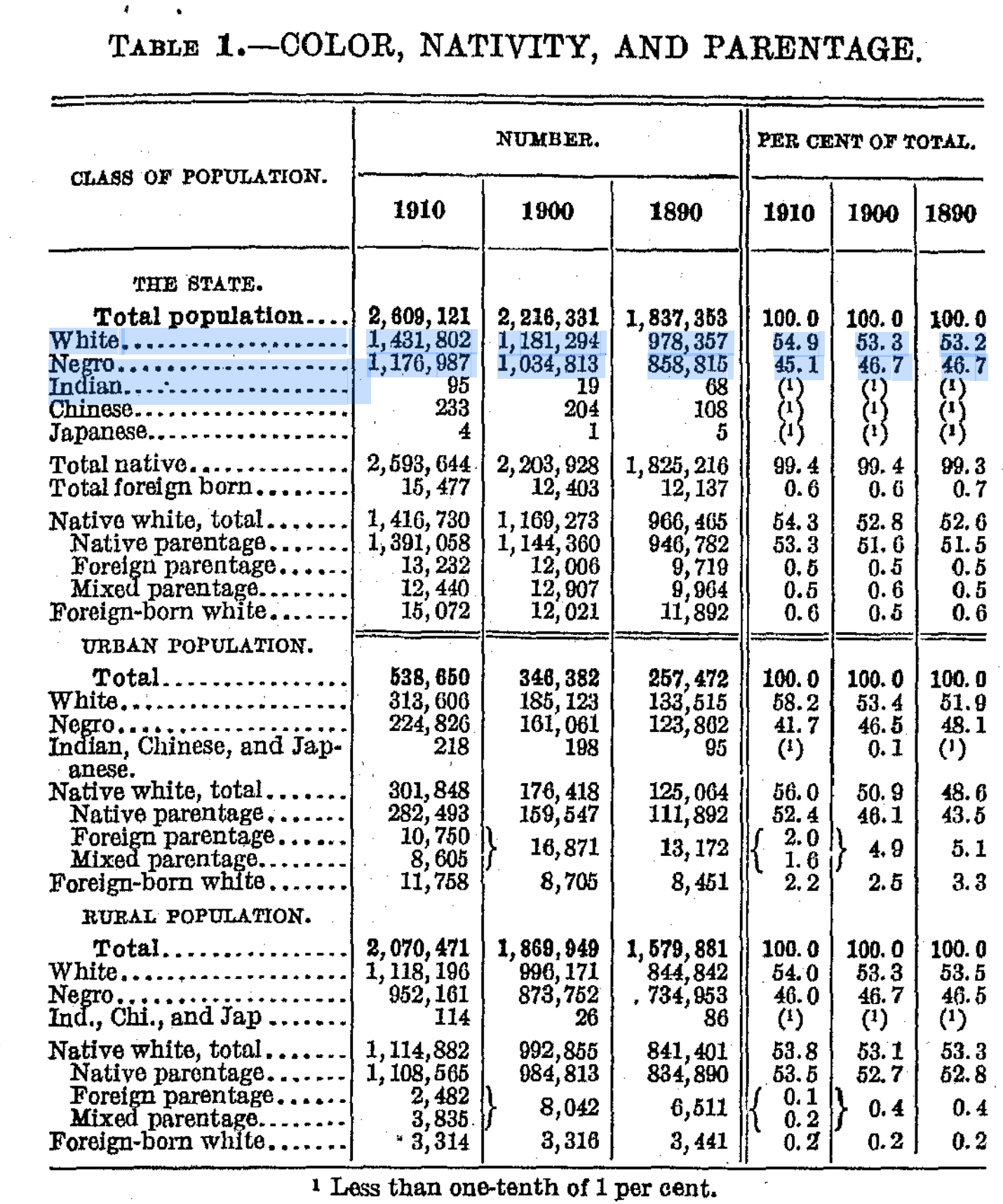

It was also the year that Georgia amended its state constitution, which resulted in the disfranchisement of the state’s Black population. It accomplished this with a Grandfather Clause. It worked by requiring voters to pass certain tests before they would be allowed to vote, but if your grandfather fought in the Civil War you were exempt from the tests.

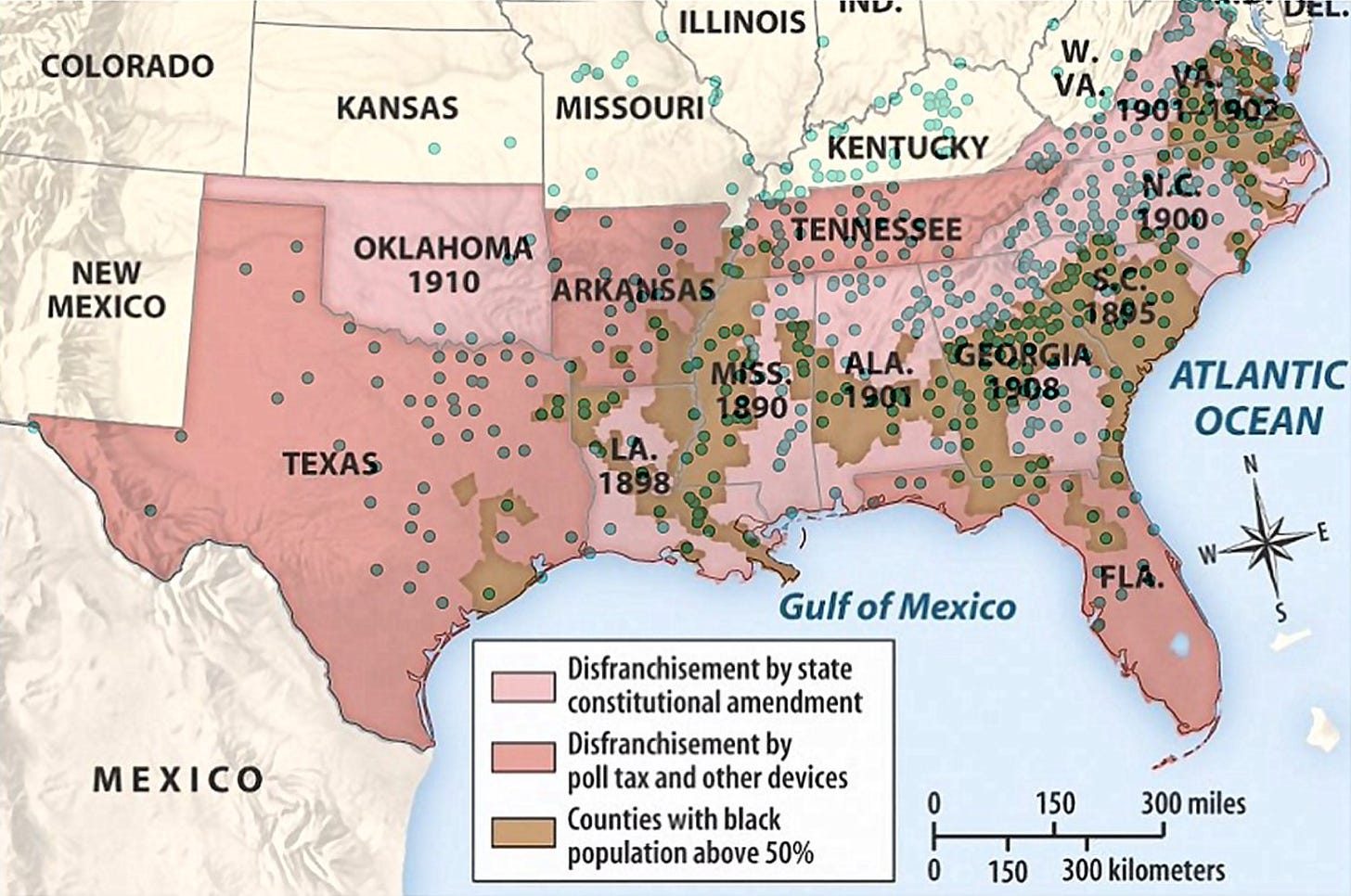

In 1910, African Americans made up 45% of the population of Georgia. In many counties Black Georgians were in the majority—as indicated by the brown color in the above map—but they had zero input as to whether a Confederate monument represented their memory of the Civil War. Every circle located in the area shaded brown represents a Confederate monument/statue dedicated in a community where more than half the population was African American.

Many have argued that today Confederate monuments no longer represent the collective values of the entire community, but the truth of the matter is that in many counties across the South, they never did.

Dekalb County’s Confederate monument was rich with inscription that sent a clear message to the white community.

East side: After forty two years another generation bears witness to the future that these men were of a covenant keeping race who held fast to the faith as it was given by the fathers of the republic. Modest in prosperity, gentle in peace, brave in battle and undespairing in defeat, they knew no law of life but loyalty and truth and civic faith, and to these virtues they consecrated their strength.

South side: Erected by the men and women and children of DeKalb County, to the memory of the soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy, of whose virtues in peace and in war are witnesses to the end that justice may be done and that the truth perish not.

West side: How well they kept the faith is faintly written in the records of the armies and the history of the times. We who knew them testify that as their courage was without a precedent their fortitude has been without a parallel. May their posterity be worthy.

North side: These men held that the states made the union, that the constitution is the evidence of the covenant that the people of the state are subject to no power except as they have agreed that free convention binds parties to it, that there is sanctity in oaths and obligation in contracts, and in defense of these principles they mutually pledged their lives their fortunes and in their sacred honor.

DeKalb County was not a majority Black county in 1908, but it included a significant number of Black residents. By the time the crowd gathered for the unveiling in 1908, African Americans had been relegated to second-class status, rendered invisible, and their history and collective memory effectively erased.

The monument itself bore witness to two generations of a “covenant keeping race” and served as a clear reminder and justification of white supremacy and Black submissiveness.

Let’s be clear, the monument never represented the entire community and was never intended as such.

Our monument landscapes reflect a wide range of factors, but one thing they clearly represent is political power—both in terms of who has it and who does not. There is a reason why Confederate monuments came to dominate much of the South in the decades after the Civil War and why monuments honoring Black and white southern Unionists did not.

Thankfully, that has begun to change over the past few decades, in large part owing to the racial profile of local and state government, which is now much more representative.

We can thank an entire generation of heroes like John Lewis for this change. His struggle to help break down the power structure that held sway in Georgia and throughout much of the country in the 1950s and 60s is a history that deserves to be recognized and honored.

John Lewis and the history that he helped to shape deserve to be recognized and honored by all Americans on the very spot that symbolized a once oppressive power structure.

Kevin, what a teachable moment!! OK to link this to our educator resources for New American History? 👩🏻💻

Great first step - a worthy next one would be passing the John Lewis Voting Rights Act into law.