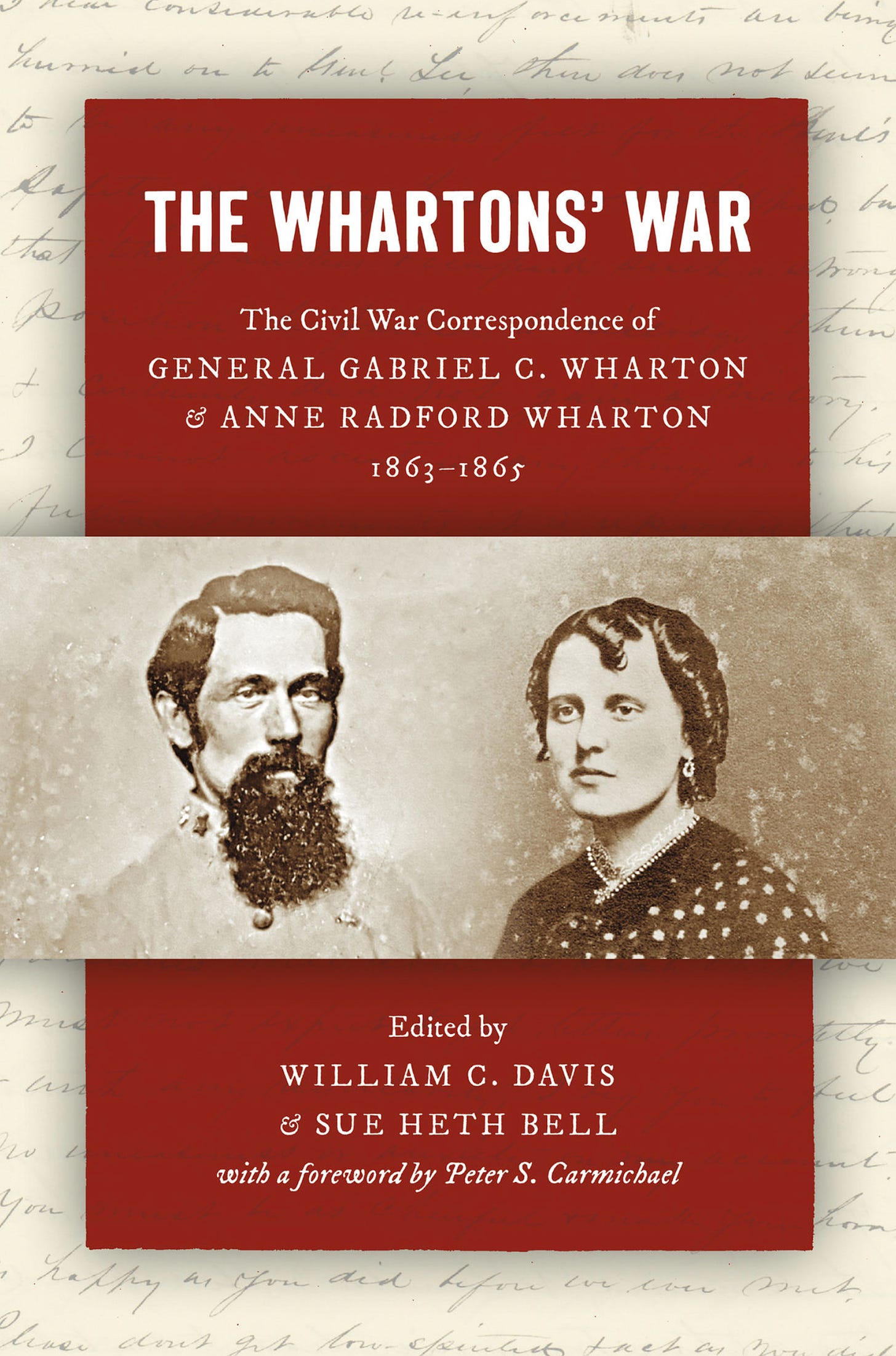

Thanks to the University of North Carolina Press for sending along a copy of The Wharton’s War: The Civil War Correspondence of General Gabriel C. Wharton & Anne Radford Wharton, 1863-1865, edited by William C. Davis and Sue Heth Bell. I’ve been looking forward to this book for some time, given how rare it is to see a complete set of wartime letters surface between husband and wife.

I really enjoyed reading the foreword from my friend and fellow historian, Peter Carmichael. His thoughts about the importance and role of empathy when studying the slaveholding class are worth sharing.

One might question the worthiness of studying white people who owned Black bodies, when they left a paper trail that today seems so inattentive to their culpability in the injustices of slavery. It is a reasonable reservation, but it should not keep us from exploring how historical actors lived, thought, and acted… To render final judgement on the Wharton’s for their failings—whether as husband and wife, as Confederates, or as slaveholders—is not particularly revealing or useful. Instead, one would do well to focus on the ways nineteenth century Virginians like the Whartons navigated the jarring contradictions between their high ideals and the ugly realities of daily life. This approach requires that we acknowledge the great distance and difference that separates us from people in the past. If we refuse to do so, we risk losing touch with valuable historical sources such as those presented here.

The correspondence between Gabriel and Anne Wharton offers a remarkable portal into a unique sensibilitiy of the past. What is commonly understood as the foreignness of history is discoverable when empathy is shown for all historical actors. Empathy should not be confused with acceptance of the unacceptable or conflated with sympathy for the detestable. Empathy is about understanding how a life in the past, which seems morally incomprehensible and unjustified today, made sense to those who were living it then. (p. ix)

There is much to consider in this excerpt. For one it is a reminder that if we have any hope of understanding the slaveholding South, we must first recognize the extent to which white and Black people were inextricably bound together. That involves having to study both the oppressors and the oppressed

As I pointed out the other day, any serious understanding of Confederates must acknowledge their humanity and that we should resist treating them as one-dimensional. As Peter notes, we can do this without minimizing or excusing the horrors of slavery.

We should approach the study of the past as we would hope future generations will one day study us in all of our complexity, contradiction, and hypocrisy.

Do yourself a favor and check this book out.

I've said before that I have no problem with the history of White people in the Confederacy as long as it is a fact-based, honest history that does not diminish the story of enslaved people. And for that matter, I think it's pretty important to bring forward this truth. Someone has to be able to provide a better narrative than groups like the SCV, the UDC or any keyboard warriors out there who are only interested in a history of the Confederacy that doesn't go beyond their comfort zone.

But I just remembered that Gary Gallagher wrote about his own experiences of navigating the dichotomy of how people see him for his acknowledgment of Confederate history. As he wrote in his book "The Enduring Civil War: Reflections on The Great American Crisis," page 11:

"My essays in Civil War Times often angered readers who deplored what they considered my transgressions against their ideological preferences. Neo-Confederates scorned my placing slavery-related issues at the heart of secession and establishment of the Confederacy or my refusal to concede that Nathan Bedford Forrest belongs alongside Lincoln as one of Shelby Foote's "two authentic geniuses" of the Civil War. To these people, I represent a typical "Marxist/communist" professor, as several have put it, who hates the South. In contrast, my suggestion that Robert E. Lee possessed considerable military skill and wrestled painfully with multiple loyalties during the era of sectional controversy brought accusations of conservative special pleading on behalf of a slaveholder and traitor who deserved to be hanged. I have two files in my study where I preserve such sentiments-the first labeled "Hate Mail from Neo-Confederates" (one correspondent hoped I would develop a "virulent form of pancreatic cancer") and the second "Hate Mail Calling me a Neo-Confederate. All such messages reminded me of advice from my graduate adviser that has guided much of my career. When I complained that recent research had forced me to change prospective conclusions, Barnes F. Lathrop curtly replied, "God damn it, Gallagher, just go where the evidence leads, and you'll be all right.""

“Empathy should not be confused with acceptance of the unacceptable or conflated with sympathy for the detestable.”

Mr. Levin, you and Professor Carmichael hit the nail on the head. There is a way, certainly within the realm of public history, that incorporates the “understanding” of the life of historical subjects in a broader perspective than a very binary “good” or “bad.” Rather, by meeting historical figures with empathy, a very basic acceptance that we will never know exactly how something “which seems morally incomprehensible and unjustified today, made sense to those who were living it then” becomes possible. Despite the circling comments below, this work and several others are valuable in analyzing the worldview of southern slaveholders, politicians, and soldiers. As historians, we should be reading a diverse swath of material that aids in research but also challenges our conceived notions, orders us to maintain objectivity and nuance, and of course, practice empathy. I’ll be adding it to the cart.