On this day in 1863 United States soldiers successfully defended Cemetery Ridge against a final assault by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg. This defeat forced Robert E. Lee to abandon his position the following day and begin a long retreat back across the Potomac River into Virginia.

Colonel John Bowie Magruder (1839-1863) led the 57th Virginia Infantry in what became known as “Pickett’s Charge.” I got to know this young colonel well while living in Charlottesville/Albemarle County, where he was born and raised.1 I walked the grounds of his plantation home, which is now an upscale housing development; walked through the ruins of the mills that his family owned on the Rivanna River; and relaxed under the same porticoes where he studied at the University of Virginia.

His beautifully written and rich wartime letters—located in Special Collections at the University of Virginia—provide insight into a wide range of subjects related to the war, but mostly they helped me to imagine what he was like as a person. Magruder was a son, brother, student, teacher, officer, and slaveholder.

The family was one of the wealthiest slaveholders in Albermarle County, Virginia increasing their holdings from twenty-seven in 1850 to fifty by 1860. When Magruder enlisted in the spring of 1861 he understood that this was a war to preserve the institution of slavery, even if he rarely touched on the subject in his letters home.

Magruder’s letters track his rise in the Confederate ranks and his experiences in battles, including Malvern Hill, Second Manassas, and Gettysburg. He took a special interest in the well-being of his men. Magruder was a strict disciplinarian, but he also understood that the morale of his men depended, in large part, in knowing that their families were safe. Magruder’s letters home are filled with requests to look into the families of his men and to forward packages to them that were mailed to the local depot.

Spend enough time with an officer like Magruder and you catch a glimpse of his humanity. Like all of us, he was a complex individual. His wartime experiences represents one of roughly 1 million men who saw service in the Confederate army between 1861 and 1865.

As historians of the Civil War era we have an obligation to understand these men in their entirety. Any attempt to reduce these men down to one simple throwaway line does nothing more than distort their stories.

Unfortunately, it has become more difficult to talk about Confederate soldiers over the past few years. Attempts to explore the history of these men beyond the subject of slavery is often interpreted as explicit or disguised Lost Cause rhetoric. Any attempt to humanize these men is viewed as racist.

This is not only a misguided approach to the past, it runs the risk of creating new myths and distortions about the Civil War. Most of my published work over the years has been an attempt to center the story of slavery in the Civil War and even in the Confederate army itself, but this can be done without distorting the lives of the men who served in their ranks and turning them into one-dimensional figures.

We can humanize Confederate soldiers without putting them on pedestals. Shortly after the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the Board of Visitors at the University of Virginia voted to remove a plaque honoring students who served in the Confederate army from in front of the Rotunda. John Bowie Magruder’s name was listed on this plaque. I agree with this decision.

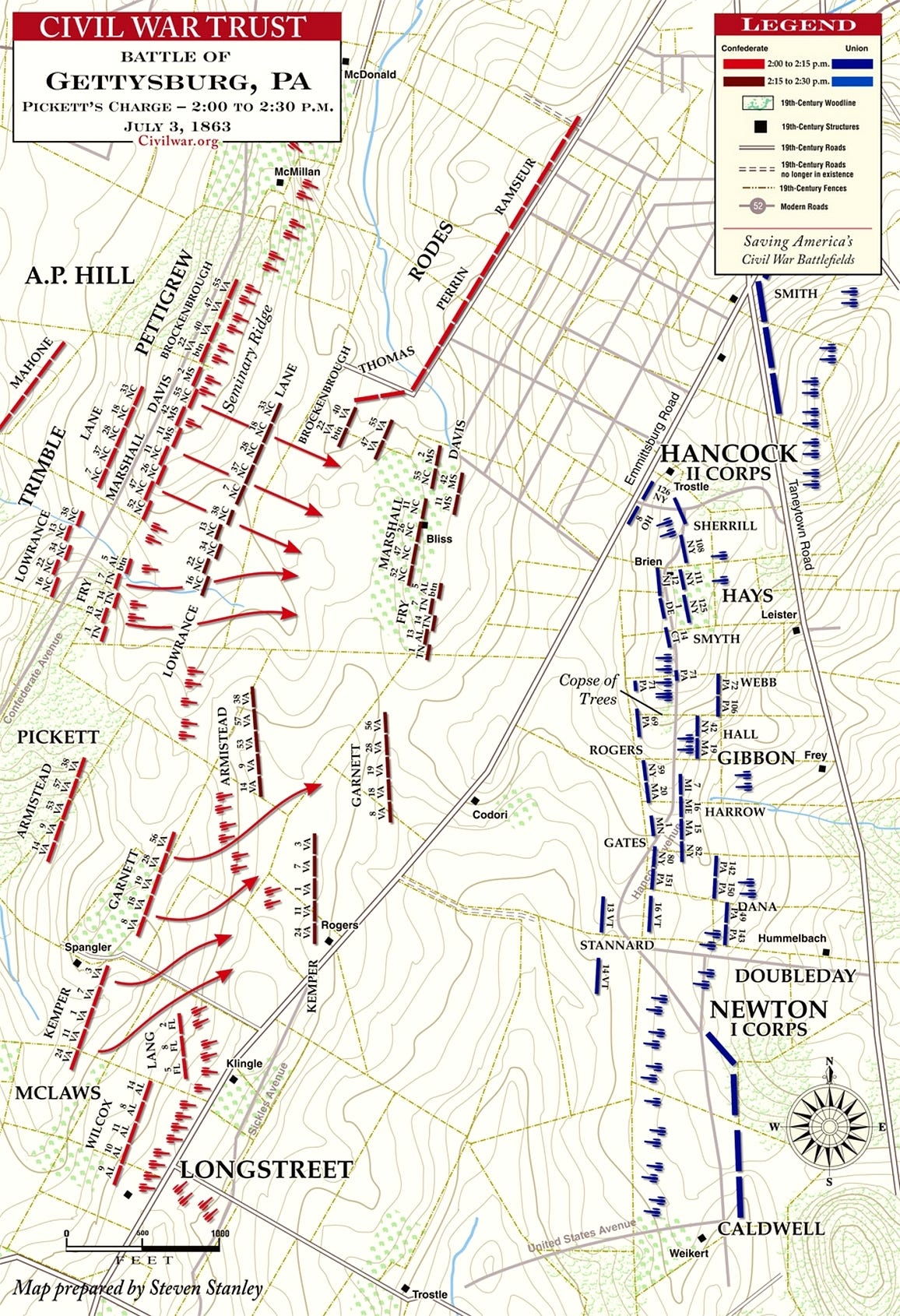

While walking along the Gettysburg battlefield, I’ve often wondered what Magruder experienced as he organized his men into line, alongside the rest of Lewis Armistead’s brigade, on the early afternoon of July 3, 1863. Even as his adrenaline and sharp sense of responsibility kept him focused once the attack commenced, I imagine him thinking of home and family.

Having never served in the military or experienced combat, I can only begin to imagine the fear and confusion that Magruder experienced as his regiment crossed the Emmitsburg Road into a hail of close range shot and shell that now had only a few hundred yards to travel from positions along Cemetery Ridge. Magruder led his men on even as the gaps in his lines grew and men continued to fall all around him.

As he made his final approach toward the Union line, Magruder is reportedly to have shouted, “They are ours! They are ours!”—likely pointing towards Lieut. Alonzo H. Cushing’s battery. Moments later Magruder fell near the famous “copse of trees,” having been struck by a bullet in the left breast and the other under the right arm. The Confederate tide crested briefly inside the Union lines before it was finally pushed back.

Magruder was taken to a Second Corps hospital, where his wounds were treated. “I will never leave this Northern land alive. Some day, when peace is restored, my friends in old Virginia will carry my bones to the ancestral burial ground. But I will never more join the family or social circle.” He did indeed succumb to his wounds on Pennsylvania soil. A few months later his remains were returned home and buried in the family cemetery.

There is much that I admire about Magruder. He was an effective and brave colonel, who led on the battlefield by example. At the same time I understand all too well that he fought for an immoral cause. Both points can be true even if they can never entirely be reconciled.

It’s all part of the challenge of exploring and interpreting the human experience.

I think, when you humanize "the other side" (whomever that happens to be), to see them as people and not monsters, it helps to clarify their mistakes, and helps to see how your own people could slide into whatever awfulness you're fighting against. We're all human, and all human societies are capable of evil. Even now, I have to remind myself what I have in common with some of the truly terrible people trying to usher in a new age of white supremacist authoritarianism.

And thank God for that successful defense.

Grant can speak for me: "I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse."