Today is the 160th anniversary of the Battle of the Crater, which is the subject of my first book. What follows is an article that I published in America’s Civil War magazine in 2006. The article offers an overview of the battle and focuses in on the massacre of United States Colored Troops committed by Confederates both during and after the battle.

In December 2003, moviegoers were treated to a vivid recreation of the Battle of the Crater in the film Cold Mountain. The engagement, fought just outside Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864, which was used as a dramatic opening movie sequence, resulted in a decisive victory for General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Though the movie did not accurately depict the dimensions of the Crater or troop movements, it did faithfully portray the fighting in and around the pit and also briefly acknowledged the presence of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) in the Federal attack.

Freed Slaves Join the Union Ranks

For many years, even as late as the Civil War centennial celebrations in the early 1960s, any mention of the importance of emancipation or the recruitment of 180,000 African Americans in the Union Army and their impact on the outcome was minimized. Only in the last few decades have historians worked to challenge long-standing assumptions concerning the central themes of the Civil War. Though Cold Mountain clearly reflects this shift in emphasis, every new step has its limits. The battle scenes failed to include any references to the well-documented cases of the execution of black soldiers who surrendered.

In addition, historians have tended to ignore wartime evidence that clearly points to a belief in the possibility of Confederate independence even as late as August 1864. Letters, diaries and newspaper articles written in the days and weeks following the Battle of the Crater contrast sharply with the way in which historians have traditionally depicted the final year of the war in Virginia. Wartime evidence also reveals that in contrast with histories written after the war, Confederates considered the presence of black soldiers at the Crater to be a salient fact that could not easily be ignored.

By the beginning of June 1864, as a result of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland campaign, Union and Confederate armies in Virginia had endured close to two months of constant fighting and horrendous casualties from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor. While Lee managed to keep his army between Richmond and the Federals, he worried about the growing likelihood and consequences of a protracted siege.

Grant’s decision to cross the James River brought the Union armies to the transportation hub of Petersburg. With five railroads connecting it to rivers and seaports, the city played a strategic role in getting supplies to Lee’s forces. Grant’s objective was to capture Petersburg by cutting off Confederate supply lines and, as a result, to weaken the defenses around Richmond.

Grant initiated assaults east of Petersburg between June 15 and 18 that made very little headway, and both armies began the tedious process of digging complex trenches and breastworks. On June 19, Brig. Gen. Robert Potter, who commanded a division in Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps, realized he was situated barely 100 yards from Confederate fortifications that, he believed, could be breached by tunneling under the position with explosives. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania, a mining engineer in civilian life who commanded the most advanced brigade in Potter’s division, confirmed Potter’s thoughts about the prospects of tunneling under the Confederate salient. Pleasants’ brigade included a contingent of miners from Schuylkill County, in the heart of Pennsylvania mining country. Potter and Pleasants shared the idea with Burnside, who enthusiastically passed the plan up the chain of command to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade and Grant, both of whom proved less enthusiastic but nevertheless allowed the digging to proceed.

The men of the 48th Pennsylvania worked from the end of June to the third week in July to complete a tunnel more than 500 feet long that branched off into two chambers at a point under the Confederate fort. Once finished, the two chambers were packed with 320 kegs of gunpowder, totaling 8,000 pounds. While Confederates were not completely in the dark about the tunnels, attempts to uncover them proved unsuccessful owing to their depth and foul weather.

The Battle

The Union high command formulated a plan to exploit the results of what promised to be an impressive and destructive explosion. Burnside proposed using Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s division, which included two brigades of black regiments, to spearhead the attack. That plan remained in place until the last possible moment, when Meade vetoed the use of black troops. Both Meade and Grant were concerned about the possible political ramifications involved in a failed assault led specifically by black soldiers. Meade amended Burnside’s plan by instructing him to use his white divisions—with Ferrero’s in support—to push straight through the anticipated breach in the Confederate lines and head for the crucial position of Cemetery Hill and the Jerusalem Plank Road, which overlooked Petersburg.

Burnside’s IX Corps included three divisions. In addition to Potter’s division, Brig. Gens. Orlando Willcox’s and James Ledlie’s divisions had been damaged to various degrees in the initial assaults on Petersburg. After drawing straws from a hat, Ledlie was given the assignment to lead the assault, even though he had previously shown signs of incompetence. The assault was set for the early hours of July 30, with the mine to explode at 3:30 a.m.

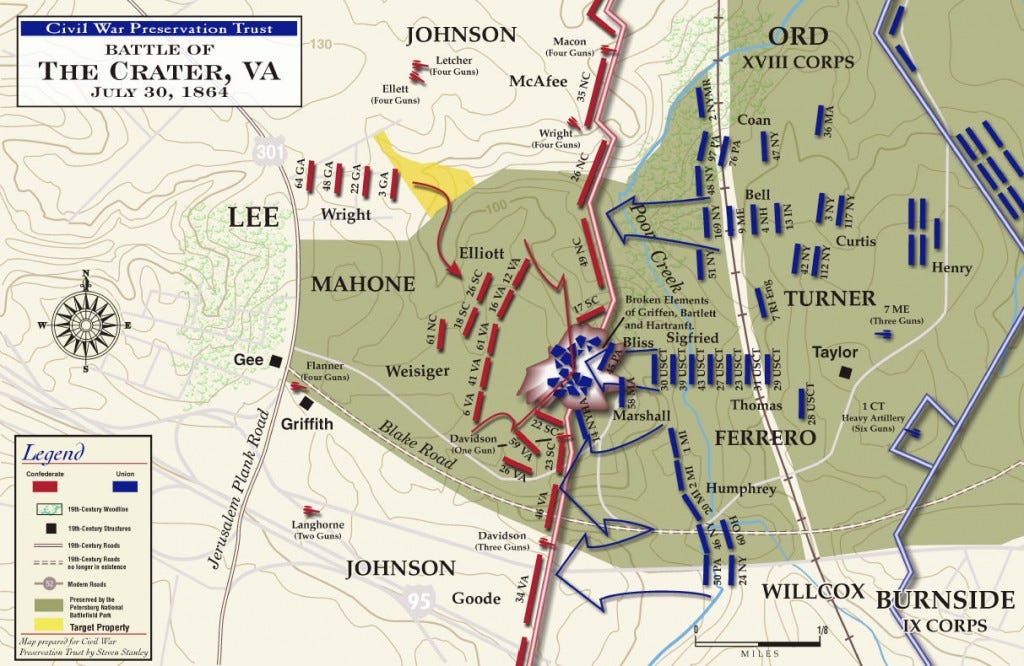

Confederate forces in the direct path of the assault were five South Carolina regiments commanded by Brig. Gen. Stephen Elliott, whose position was known as “Elliott’s Salient.” On Elliott’s north and south were positioned the commands of Maj. Gen. Robert Ransom’s North Carolina brigade, now under the command of Colonel Lee McAfee, and Brig. Gen. Henry Wise’s Brigade, now led by Colonel John T. Goode. Captain Richard Pegram’s four-gun battery, positioned with Elliot’s Brigade, provided artillery support.

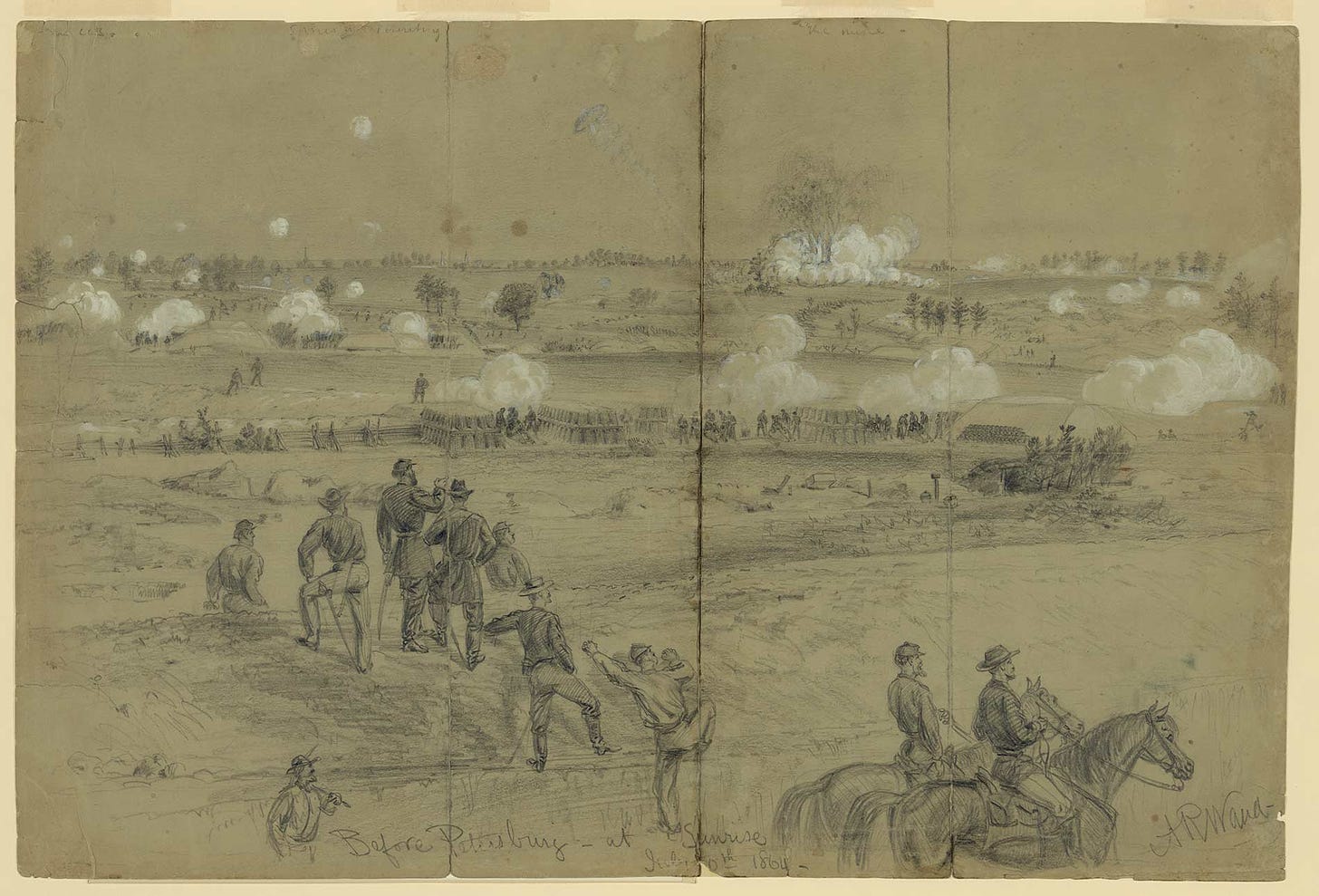

Because of a deficient fuse line, the explosion and subsequent attack set for 3:30 a.m. was delayed until roughly 4:45 a.m. The explosion left a hole in the ground 150 to 200 feet long, 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep, and killed or wounded 278 of the 300 men in Elliott’s Brigade, plus 30 gunners in Pegram’s Battery. A soldier serving in the 118th New York Regiment recalled, “The fort was fairly blown right up into the air—it was a splendid sight.” “Earth and heaven were rent by an explosion,” wrote John Haley of the 17th Maine, “that would have done credit to several thunderstorms.” The Union assault began with a massive artillery barrage along nearly two miles of trench lines.

Not knowing what to expect, Ledlie’s brigade pushed toward the scene of the explosion, where they encountered a horrific sight. Body parts protruded from the loose Virginia clay; scores of men in Elliott’s Brigade never had a chance, as the explosion occurred while they were sleeping. Rather than moving quickly onto the vulnerable crest of Cemetery Hill, Ledlie’s men dug in on the far side of the Crater. Brigade commanders seemed uncertain as to their goals, which was largely because of the absence of General Ledlie, who drank away the morning in a bombproof shelter.

Once the initial shock of the explosion subsided, the remnants of Elliott’s Brigade and other Confederate units took up a defensive position in a shallow trench and turned as much firepower on the advancing Union brigades as possible. Ledlie’s brigade was followed by the brigades of Potter, which took up a position on Ledlie’s right, and Willcox, situated on the left. Within one hour close to 7,500 Union troops were defending a perimeter not much larger than the outlines of the Crater itself. Stubborn Confederate resistance resulted in great confusion in the Union ranks and made any further Union assault difficult to organize. To add more confusion to the situation in the Crater, around 8 a.m. Ferrero’s division of black troops was ordered to advance, and their organization quickly disintegrated.

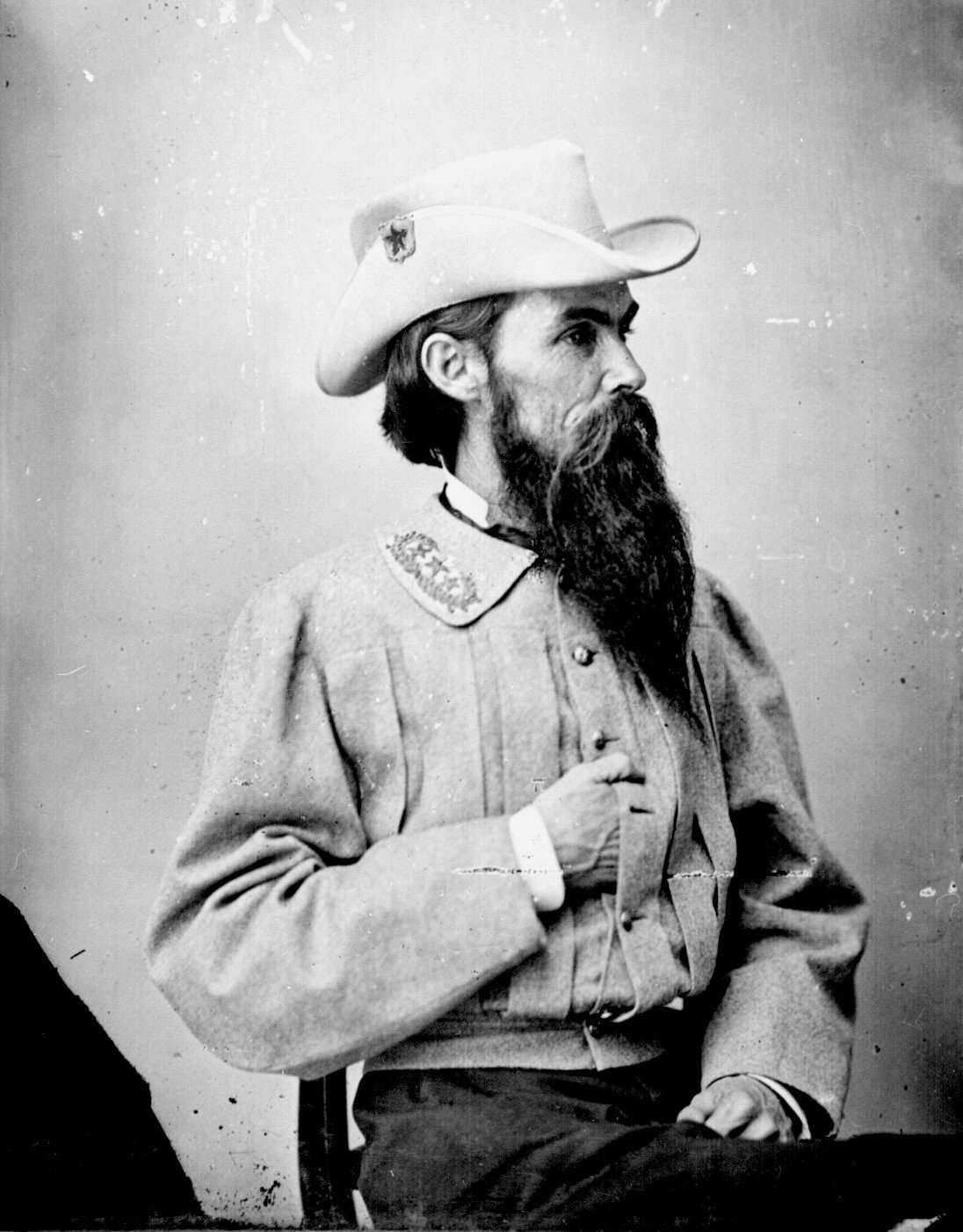

Union officers tried to organize an assault on what was still a thinly defended position. The day could still be won, but opportunity for that advance was quickly canceled, as Confederate Brig. Gen. William Mahone arrived with two of his brigades .Mahone’s Division was positioned about one mile southwest of the Crater when he was ordered by Lee to move reinforcements to buttress the line. Colonel David Weisiger’s Virginia brigade and Colonel Matthew R. Hall’s Georgia brigade were ordered by Mahone to move to Cemetery Hill. Mahone’s men advanced along the Jerusalem Plank Road until they turned east along a covered way to a ravine that branched north and west of the Crater. As the two brigades rushed to take up position, Mahone ordered Colonel John C.C. Sanders’ Alabama brigade to the front. Weisiger’s Virginians took up a north-south line of battle that faced the Crater to the east, with Hall’s Georgians extending the line farther north. At approximately 9 a.m., Weisiger was ordered forward.

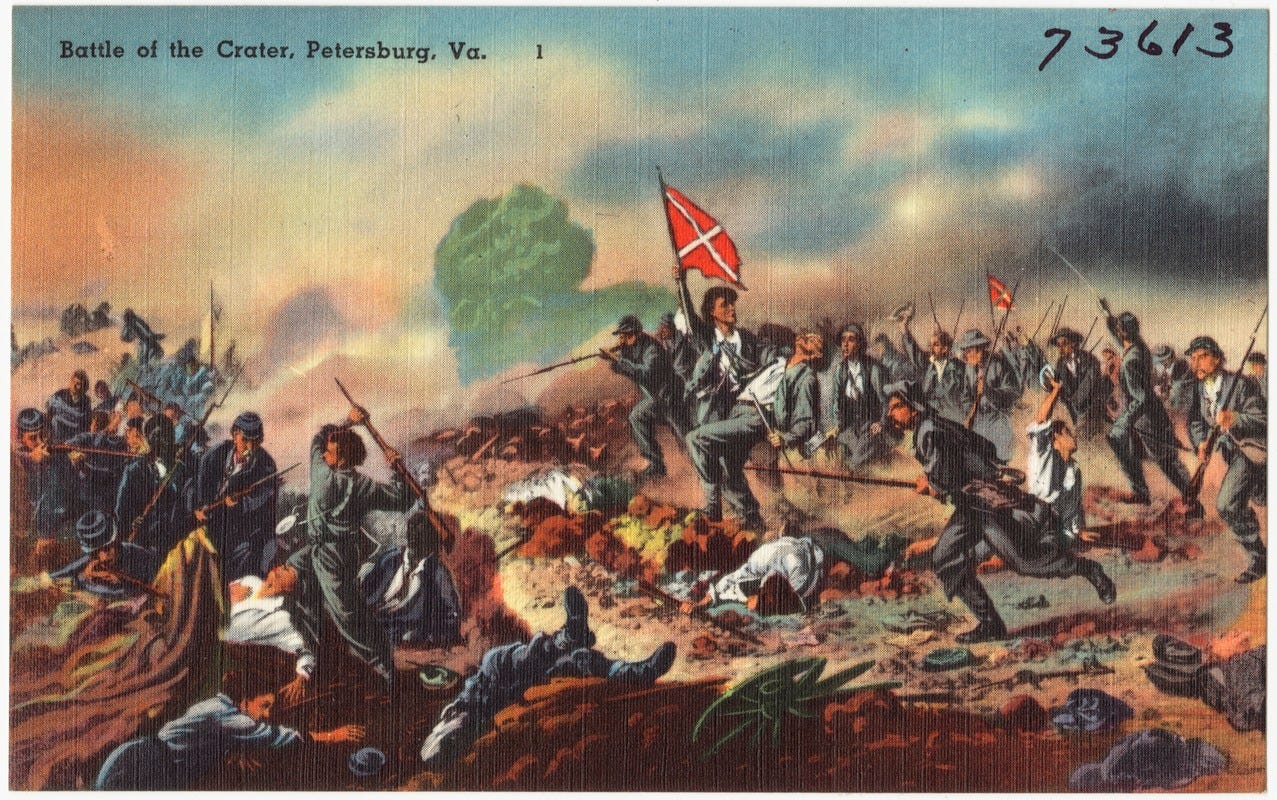

At the height of the Union assault, Federal units advanced to occupy two separate lines and were close to occupying a third when, as one Union soldier recalled, “The rebel general suddenly…had thrown [his troops] forward with the determination of recovering the ground he had lost.” Mahone’s Virginians slammed into the western face of the Crater, inflamed by reports that African-American soldiers were part of the attacking Union force, while Hall’s Georgians moved against the northern rim of the Crater with less success, in part because of concentrated artillery fire. John Cheves Haskell’s mortar battery added to the chaos.

At approximately 1 p.m., Mahone ordered Sanders’ Alabamans into the mix, and the attack proved to be the final assault of the battle. Union soldiers either surrendered or attempted to flee. Many of those who fled were cut down by a deadly crossfire. Union regiments stationed between the Crater and their own lines were given the job of restoring order.

The official report put the Union dead at 504, plus another 1,881 wounded and 1,413 reported missing. Confederates suffered 361 killed, 727 wounded and 403 missing. Early on the morning of August 1, a truce was declared so both sides could retrieve their wounded and bury their dead. To the jeers of locals, both black and white Union prisoners were paraded through Petersburg.

In the days following the Battle of the Crater, Confederates attempted to make sense of a battle that had deviated significantly from previous experiences. The novelty of the Union plan of attack, the destructive power of the explosion and the resulting surprise and awe were topics of widespread interest. Sergeant William Russell of Wise’s Brigade heard “a tremendous dull report and at the same time felt the earth shake beneath me.” He described the immediate aftermath of the explosion as “an awful scene.” Another Virginia soldier recalled, “A deep rumbling sound, that seemed to rend the very earth in twain, startled me from my sleep, and in an instant I beheld a mountain of curling smoke ascending towards the heavens, on the left of our lines.”

The paucity of accounts from Elliott’s Brigade attests to the destructiveness of the explosion. Many were killed outright or buried alive in their sleep. Lieutenant Pursley of the 18th South Carolina had just gone to sleep in a bombproof shelter when “the first jar I felt I thought it was a bomb had lit on my little bomb proof….Just as I lit in to the ditch there came another blast & God only knows how high it sent me….I spread out my wings to see if I could fly but the first thing I knowed I was lying on top of the works….” In a letter to the parents of John W. Callahan of the 22nd South Carolina, Daniel Boyd conveyed the destructive power of the explosion by illustrating the conditions in which their son was discovered: “J W Calahan Was Kild by the blowing up of our breast Works he was buried wit[h] the dirt. When they found him he was Standing Straight up the ditch their was one hundred kild and buried with the explosion.”

Josiah F.Cutchin, who served in the 16th Virginia, recalled the hand-to-hand combat “in the trenches…fighting as hard as they could with the Bayonets and the buts of their guns.” According to Cutchin, “The blood in the trenches was a shoe sole deep.” “The field was literally covered with dead bodies,” commented John F. Sale, “and everyone could have started from our works and walked to theirs without touching their foot to the ground, but by stepping from body to body.” According to David Holt of the 16th Mississippi, the fight in the Crater “beat the bloody ditch at Spotsylvania and the Yankee breastworks at Chancellorsville.”

Beyond the sheer horror of fighting in the Crater surrounded by buried and half-buried comrades, Confederates were aghast to learn that the enemy included an African-American division. Private Henry Van Lewvenigh Bird of the 12th Virginia recalled proudly, “The negro’s charging cry of ‘No quarter’ was met with the stern cry of ‘amen.’” Writing after the war, one Union veteran was surely correct when he noticed that for a Confederate soldier, “It seemed to add increased poison to the sting of death to be shot by a negro. The Confederates considered such an act as violating all rules of warfare and the sacred rights of humanity.” For many of the men, the Crater gave them their first experience fighting black soldiers, and their response suggests a heightened sense of rage and purpose. “It had the same affect upon our men that a red flag had upon a mad bull,” was the way one South Carolinian described the reaction of his comrades. David Holt remembered, “They were the first we had seen and the sight of a n—— in a blue uniform and with a gun was more than ‘Johnnie Reb’ could stand.” “Fury had taken possession [of me],” he said, adding, “I knew that I felt as ugly as they looked.”

Many Confederates relished retelling their experiences in the Crater fighting Ferrero’s division. “Our men killed them with the bayonets and the buts of there guns and every other way,” according to Labnan Odom, who served in the 48th Georgia, “until they were lying eight or ten deep on top of one enuther and the blood almost s[h]oe quarter deep.” Another soldier in the 48th described the hand-to-hand combat: “The Bayonet was plunged through their hearts & the muzzle of our guns was put on their temple & their brains blown out others were knocked in the head with butts of our guns. Few would succeed in getting to the rear safe.”

Even after acknowledging the bravery of the black soldiers in the Crater who “fought us till the veary last,” John Lewis of the 61st North Carolina of Hoke’s Division was satisfied that “we kild asite of nigers.” Lieutenant Colonel William Pegram described in great detail for his wife situations where black soldiers “threw down ther arms to surrender, but were not allowed to do so. Every bombproof I saw had one or two dead negroes in them, who had skulked out of the fight, & been found & killed by our men.”

The presence of black soldiers even served as a rallying cry for Confederates who did not participate in the battle. Describing how “[o]ur men bayoneted them & knacked ther brans with the but of their guns,” as did Lee Barfield who served in the 62nd Georgia Cavalry, might have been the next best thing to being there. Even A.T. Fleming, who served in the 10th Alabama but missed the battle because of illness, could not help but allow his racist preconceptions to pervade a very descriptive account in which Confederates “knocked them in the head like killing hogs.”

Once the salient was retaken, Confederate rage was difficult to bring under control. Accounts written in the days following the battle rarely shied away from including vivid descriptions of the harsh treatment and executions of surrendered black soldiers. Robert G. Evans of the 16th Mississippi recalled: “Most of the Negroes were killed after the battle. Some was killed after they were taken to the rear.” Another soldier admitted that “the poor deluded devils were butchered right and left.”

Lieutenant Freeman Bowley of the 30th USCT wrote, “As the Confederates came rushing into the Crater, calling to their comrades in their rear, ‘The Yankees have surrendered!’ some of the foremost ones plunged their bayonets into the colored wounded.” “The only sounds which now broke the silence,” according to Henry Van Lewvenigh Bird, “was some poor wounded wretch begging for water and quieted by a bayonet thrust which said unmistakably ‘Bois ton sang. Tu n’aurais de soif.’[Drink your blood. You will have no more thirst].” James Verdery simply described it as “a truly Bloody Sight a perfect Massacre nearly a Black flag fight.”

Following the Battle

Colonel Sanders was forced to admit that the “Negroes…fight much better than I expected.” However, he was quick to qualify this statement with the conviction that “they were driven on by the Yankees and many of them were shot down by the latter.” J. Edward Peterson, who served as a band member in the 26th North Carolina, described the black soldiers at the Crater as “ignorant” and assumed they were forced to fight by the Yankees. Peterson went on to conclude that because of that they did not deserve such harsh treatment by Confederates following the battle.

As a result of fighting black soldiers, many Confederates experienced a renewed sense of purpose and commitment to the cause. Years after the war, Brig. Gen. Edward Porter Alexander remembered that the “general feeling of the men towards their employment was very bitter.” “The sympathy of the North for John Brown’s memory was taken for proof,” according to Alexander, “of a desire that our slaves should rise in a servile insurrection & massacre throughout the South,& the enlistment of Negro troops was regarded as advertisement of that desire & encouragement of the idea to the Negro.” Colonel William Pegram also acknowledged the perceived threat as stated by Alexander when he noted, “I had been hoping that the enemy would bring some negroes against this army.” And now that they had, “I am convinced…that it has a splendid effect on our men.” Pegram concluded, “It seems cruel to murder them in cold blood,” but the men who did it had “very good cause for doing so.” Fighting black soldiers for the first time served to remind Lee’s men of exactly what was at stake for the Union in the war—nothing less than an overturning of the racial hierarchy of their antebellum world.

The relative ease with which Lee’s men repulsed the Union attack had a positive effect on their overall morale. Confederate success generated a renewed confidence that future Federal attacks could be repulsed. After the battle, Sergeant Hugh Deason of the 10th Alabama said, “Our prospects are brighter now.” Deason was “anxious” for an “honorable peace,” but refused to lay down his arms without the “recognition of the Southern Confederacy….This present generation will never live to see the South subdued, no never.”

After hearing from family about the progress of the war elsewhere, Ham Chamberlayne predicted, “If they will whip Sherman, we will finish the war here—For Grant is at a deadlock.” “Such blow ups do not pay,” asserted Robert Evans. “A few more such and Grant will have a corps less….” In response to his aunt’s question of what he thought of Grant, John F. Sale remarked, “He has outnumbered us two to one all this time, but for all that he has gained no decided advantage.” Another observer concluded that Grant was “no more a match for our Noble Lee, than an Ethiopian.”

Beginning in the middle of June, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s raid into Maryland also occupied the attention of those in the Petersburg trenches. Optimism about Early’s prospects heightened the hopeful outlook that accompanied success at the Crater. Victory at the Crater no doubt raised expectations even as Early’s men were moving their base of operations from the outskirts of the capital to the Shenandoah Valley. Though he did not see action at the Crater, writing just two weeks after the battle, Robert Campbell remained optimistic after connecting the recent victory with events elsewhere: “Gen. Early has been near enough Washington to serenade ‘Old Abe’ with the tune of Dixie. We all have confidence in our success. We believe that God is with us.”

The fight at the Crater also added to the belief that continued success might cost Abraham Lincoln the Northern presidential election. Paul Higginbotham reminded his relatives back home that many of his comrades believed “old Abe will be defeated for President. I am confident we will yet again gain our independence, if we are true to our cause and Country.” Lieutenant Henry Smith, who served as an aide to Maj. Gen. Charles W. Field, waited for the results of the Republican convention in Chicago with “much interest and anxiety.” Smith remained hopeful that “something will turn up that will bring about an adjustment of our national trouble.”

Success on July 30 also reinforced faith in Lee’s ability to steer the Army of Northern Virginia toward eventual victory. J. H. Claiborne, who worked in the Office of Senior Surgeon in Petersburg at the time of the battle, eloquently summed up the thoughts of many concerning Lee: “No man on this continent or any other now fills so large and important a place to so many people. I verily believe, under God, our whole cause is in his hands; and if he goes down the hope of the nation is extinct….The people and the Government unite on him only.”

In the wake of the battle, newspapers echoed the optimism of the men in the trenches. “Entering this war with the declaration that the ‘rebellion’ would be suppressed in ninety days, by the force of numbers,” noted the Sentinel of Richmond, “the war has continued for more than three years, the United States being weaker to-day than when hostilities commenced while the Confederate States are infinitely better prepared than ever before to resist the attacks of the enemy.” Virginia’s Lexington Gazette noted approvingly an article from a London paper, which indicated that “the longer this struggle goes on, the greater will be the appreciation of our conduct and our cause.”

“Grant’s campaign is a failure, it has probably ended [h]ere in terrible disaster. And it is in such a war, it is to reap disaster after disaster, humiliation instead of triumph,” concluded this writer, “that Americans are sending their sons to die at the rate of 1,000 daily, and expending each day a sum of half a million sterling.” A more balanced account was offered by the Charleston Mercury, which suggested that while the Union campaign could be considered a “grand failure,” the Northern war effort would continue unabated: “Grant is a believer in Lincoln, and that Great Tycoon of Yankeedom long since announced his determination to keep [hammering] away at the rebellion until it should be crushed.”

An analysis of wartime accounts points to certain conclusions concerning how Confederates viewed the progress of the war in the late summer of 1864. For many, the decision to detonate a large amount of explosives under unsuspecting soldiers in the pre-dawn hours, plus the inclusion of black soldiers in the attack, confirmed that the Lincoln administration and the North had abandoned any sense of morality or decency. Though the fighting in and around the Crater reached a new level of ferocity, the relative ease with which Confederates were able to retake the salient translated into a firm belief that Grant’s formidable host could be resisted, at least for the immediate future.

Events elsewhere contributed to this sense of optimism. As long as Lee could repulse Grant’s offensives around Petersburg and Jubal Early continued to operate in the Shenandoah Valley and Maryland, there was the chance that Northern voters might grow weary of a protracted war and replace Lincoln with someone, perhaps George B. McClellan, who might discontinue the war and thus bring about Southern independence. In contrast to postwar accounts, which treated the Petersburg campaign as part of an inevitable decline in Southern prospects for victory in the post-Gettysburg period, a closer look suggests that Lee’s men remained weary but hopeful.

My great grandfather served in the cavalry in the Civil War, a fact I grew up knowing. What I didn't know was that his regiment was scorned and denigrated..When the war ended they were ordered to go to Texas to guard the border to stop any confederates that might try to escape. They were beaten threatened and physically dragged to the border. The war was over they wanted to go homebecause of this they got a bad name. They were in the only African American Cavalry formed in the North.

My ancestor was Charles Henry Tyler a Private in company F, 5th Regiment Massachusetts Cavalry.

You know those Lost Causers who try to weasel on the actual history by declaring that "most southern soldiers didn't own slaves"--that they fought only to repel invaders? Kevin's essay here contains what I see as this nice distillation of why that argument is colossally bogus:

"Fighting black soldiers for the first time served to remind Lee’s men of exactly what was at stake for the Union in the war—nothing less than an overturning of the racial hierarchy of their antebellum world."