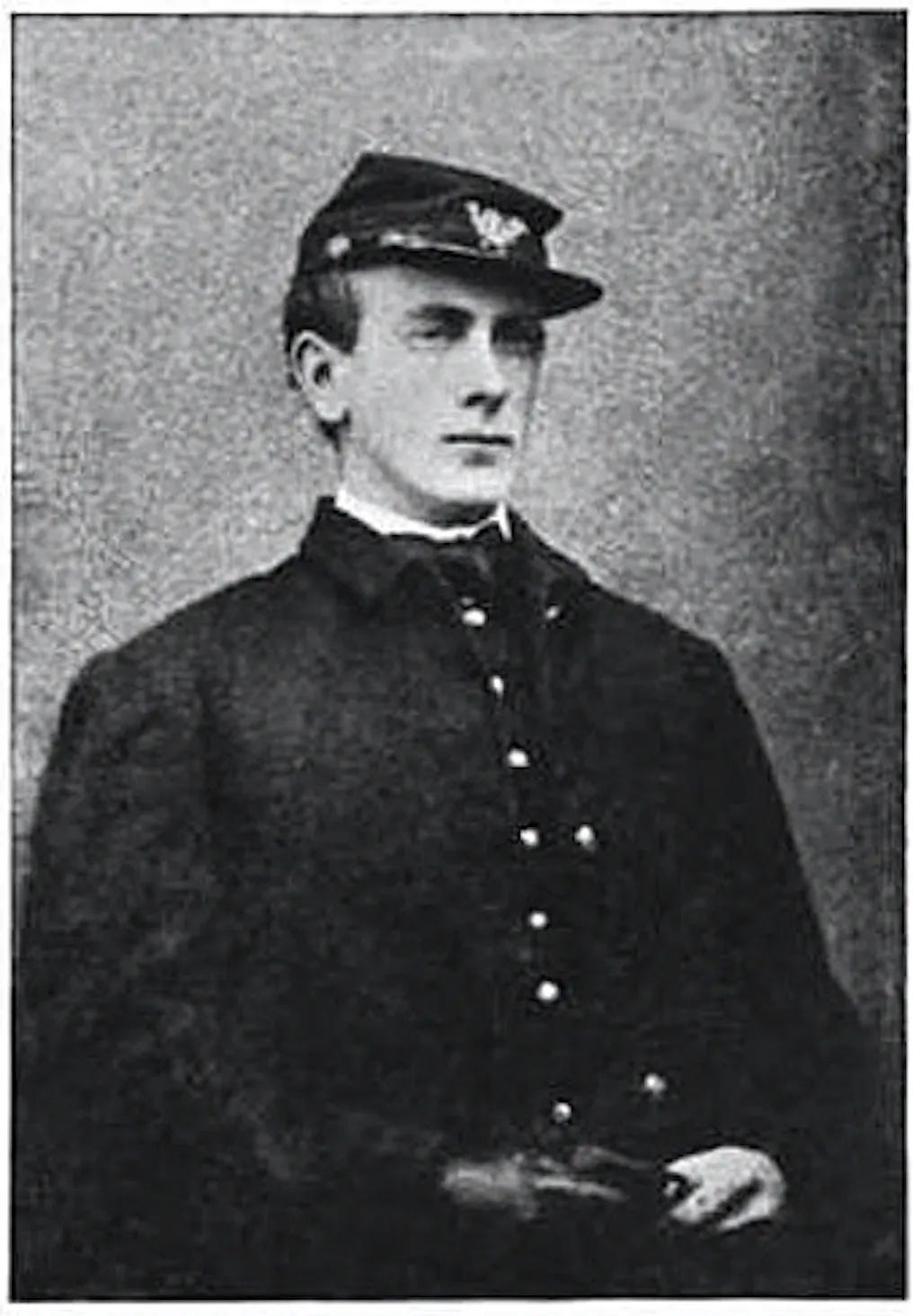

Of all the source that I have examined in the course of my research on Robert Gould Shaw, none has proven more important (other than his own correspondence) than that of Charles Fessenden Morse, which the Massachusetts Historical Society has digitized and made available to the public.

Morse served with Robert Gould Shaw in the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, throughout 1861 and 1862, before the latter accepted the colonelcy of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in February 1863.

Donovan Leitch Jr. plays Morse in the movie GLORY, but he only appears a few times throughout the film. Unfortunately, he didn’t have any lines in the movie, but you can pick him out in a few places owing to the large hat that wardrobe put on him. He does appear in the final scene during the battle sequence at Fort Wagner. It should be noted that Morse did not join Shaw when he left the 2nd to take command of the 54th Massachusetts.

Morse’s letters are incredibly detailed, especially his descriptions of the battles of Winchester, Cedar Mountain, Antietam, and Chancellorsville. Shaw and Morse were incredibly close and his name comes up often in these letters.

Here are a few excerpts. Most of Morse’s letters were addressed to his father:

January 31, 1862: Last Saturday I was on guard, Bob Shaw came to [?] and proposed as we couldn’t go home that we should try and get 48 hours leave from Genl Banks, and go down to Annapolis and see our friends Curtis and Higginson. I agreed of course and signed my name to an application. He took them and carried them himself to Gordon, Abercrombie & Banks who all approved. We made our arrangements to start from Frederick early Monday morning, [and] got leave from the Col to get into Fr. Sunday night… We arrived at Baltimore at 10 A.M. and took carriage for the Gilmore House, here we washed and polished up, then took a stroll ‘round the city. As I never have been in but very few cities I can’t be good at comparison, but I was extremely pleased with Baltimore, it seemed so much like Boston that I kept imagining I was on Washington St, the people too had a very Boston look; we visited the Washington Monument, and went to the top, both making up our minds on the stairs we never would go up such a place again, the view of B. from the top however, was very fine commanding the whole city and surrounding country. After this we promenaded ‘round for an hour or two looking at the people, [?]. But the best fun of all was meeting on Charles St. two ladies one right after another both aristocratic looking and very richly dressed, who as they passed us, gave their dresses a slap and swept off to the further side of the sidewalk, giving us the widest berth possible as if we were the plague; of all ridiculous performances this was the richest I ever saw. I thought they had got used to our blue coats before this. We took a lunch in the morning at Guy’s, of most delicious boiled oysters and ale. At two we had dinner, a first rate one, soup, fish, prairie hens, pudding pies fruit, etc etc and a bottle of elegant sherry.

June 5, 1862: Bob Shaw was struck by a Minnie ball, which passed through his coat and vest and dinted in to his watch, a very valuable gold one, shattering the works all to pieces, doing him no danger with the exception of a slight bruise. The watch saved his life, he has sent it home.

September 22, 1862: During the rest of the battle we were on different parts of the field, supporting batteries. We laid down that night about 10 o’clock glad enough to get a little rest, the dead and dying were all around us, and in our very midst, it was dreadful… I found that Bob Shaw and I had slept within fifty feet of a pile of 14 dead rebels, and in every direction about us they were lying thick.

November 14, 1862: Yesterday Bob Shaw and I visited all the places where we were engaged [at Antietam], saw where our men were killed etc. We could follow our first line along by the graves; next to ours, came the 3d Wis who lost terribly in this place; next to them was a battery that was splendidly fought, where it stood in one place, there are the remains of fifteen dead horses lying together so close that they touch each other; farther on towards our left we found numerous graves belonging to 28th Penn men, they were in a wood; every tree in the vicinity is scarred by bullets, and the branches torn by shot and shell. No language could describe more forcibly, the severity of the fight. It is hard to realize in riding through these now peaceful and beautiful woods, that they could have been so lately filled with all the terrible and dreadful sights and sounds of a great battle. I thought that I should like to have the whole roar and tumult of the battle burst upon us as we stood there, and listen to it for a few minutes. How pleasant it would be when these battles are parts of our history, and the war is over, to visit these fields with you and father and show you the interesting places; it seems like looking forward almost to another life to think of such a thing.

March 1863: I’m very glad mother and Ellen liked Bob Shaw so well at first seeing him, but you’ve got to know him as I do, to know what a thoroughly good fellow he is; I hear from him very often. He writes in fine spirits about his regiment and doesn’t doubt of the success of it. We four fellows Curtis, Russell, Shaw and myself are pretty well separated now, and each has got his own track to run in, but I believe we each feel the same interest in one another as if we were altogether as we used to be.

October 4, 1863: I called on Mr. Shaw at his office; he was very much affected I think at seeing me, whenever he had met me before it had been with Bob. I found that his family were all staying at Staten Island so it was impossible to see them.

This is just a small sample of what I found. Shaw spent countless hours talking with Morse and fellow officers about a wide range of subjects. Many of them had attended Harvard and lived in and around Boston and Cambridge. They were all from elite New England families and shared similar cultural and political views.

These young men relied on one another in more than one way, but I get the sense that Shaw and Morse were especially close.

Letters and diaries from Shaw’s closest friends are indispensable to understanding his view of the war, including generals like McClellan and Nathaniel Banks Jr., enslaved people, emancipation, the civilian population of the South, and the broader progress of the war.

I also believe that understanding Shaw in the context of the 2nd MVI helps us to more clearly see what I believe to be a fairly significant gulf between how he viewed the war and his parents. This gulf widened throughout 1862 and came to a head in the wake of the release of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862.

More importantly, I don’t think it is possible to understand the few months he was in command of Black soldiers without understanding the much more extensive period of time he spent with the 2nd. This is a seriously understudied aspect of Shaw’s military career.

Thanks for shining a light on CFM. As you probably know, he had six children and named the youngest Thomas Robeson Morse in honor of his friend Captain Thomas Rodman Robeson, KIA at Gettysburg. Skipping over the irrelevant genealogy, "Uncle Tom" Morse was my grandmother's brother-in-law, the long time head of Belmont Hill School, and very much a connecting point for my own childhood interest in the Civil War. He died in 1996 at 100 years of age. CFM's son Arthur Holdrege Morse married Colonel Pen Hallowell's daughter Esther.

These are some extremely affecting passages. Thanks for posting.