Something about this blog post about about Robert E. Lee as a father, published yesterday at Emerging Civil War, rubbed me the wrong way after I read it this morning. It’s not the content per se, but the context in which it is presented.

It was published on Father’s Day.

As a historian, I certainly expect a biographer to offer as rich a picture of its subject as is warranted by the available evidence. In the case of Robert E. Lee that includes his domestic life and role as a father. But in the case of a biography that aspect of his life is explored as part of a whole. It offers a window into one small aspect of a complicated and rich life experience.

Singling out this part of Lee’s domestic world on Father’s Day, however, is something entirely different.

It turns out that the Confederate “marble man” was an enthusiastic tickler:

Apparently, the great R. E. Lee, as a 30-something father, loved tickle fights with his younger children. I know! You won’t picture him the same after that revelation. Rob remembered his father ‘was always bright and gay with us little folk romping playing and joking with us.’ He ‘was very fond of having his hands tickled and what was still more curious it pleased and delighted him to take off his slippers and place his feet in our laps in order to have them tickled.’ Okay, it’s more of a tickle capitulation game, but still…

Lee enjoyed playing sports with his boys, adopted animals for their enjoyment, and mourned their loss.

Let me be clear, that as students of history we need to exercise empathy and acknowledge the humanity of everyone we study in the past. Failure to do so almost always leads to treating them as a means to an end rather than attempting to provide as complete a picture of their lives as possible and the world in which they lived.

But as a Father’s Day post, I can’t help but think about the larger context of slavery and the families that were destroyed during its long history. More specifically, I can’t help but think about the families that were destroyed more directly by Lee and the conduct of his army and other Confederate armies throughout the war.

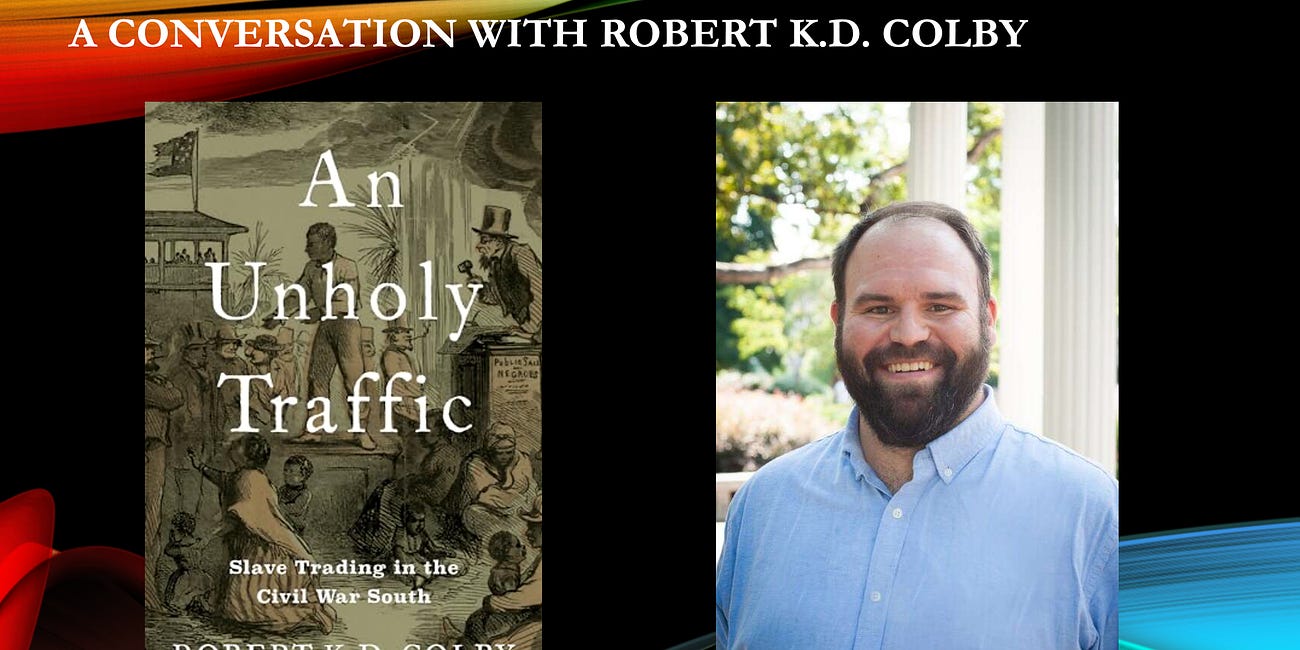

Perhaps this is on my mind having recently finished Robert K.D. Colby’s fabulous new book, An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South.

[Check out my author interview with Dr. Colby]

Colby argues convincingly that the slave trade depended, in large part, on the success of Confederate armies. There was nothing inevitable about the end of the slave trade at the beginning of the war. It experienced dips and increases as the war progressed.

Confederate armies, including the Army of Northern Virginia, had a direct impact on the lives of the enslaved. Consider the Maryland Campaign of 1862. The surrender of Harpers Ferry imperiled the lives of many African Americans. As the historian Scott Hartwig notes:

The majority of the black people who were taken, however, were not as fortunate. A considerable number were claimed by masters who lived nearby, but many others were sent by rail to Richmond. The Richmond Dispatch recorded that there were men, women, and children in this group, and that they were owned (or at least reputed to be owned) by Virginians living near Harpers Ferry. The Richmond Dispatch observed that the negroes were being transported south because ‘their masters propose to offer them for sale in Richmond, not deeming them desirable servants after having associated with the Yankees.—To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign of September 1862 (p. 565)

The following year Lee’s army reportedly kidnapped hundreds of free Blacks in south central Pennyslvania during the Gettysburg Campaign and had them transported to Richmond for sale thus separating countless families.

As Colby documents, families were forcefully separated right up until the very end of the war.

Historian Judith Giesberg and her team at Villanova University have done a fabulous job of tracking the attempts on the part of former slaves to reunite with loved ones in the wake of the war.

Thankfully, there were a few success stories.

I don’t mind acknowledging that I am glad that Robert E. Lee had the opportunity to enjoy his family for a few short years after the Civil War before his death in 1870. No doubt, their presence helped to begin to heal the many physical and psychological wounds opened by so many years of war.

But when it comes to Lee and the war, I want to remember and acknowledge the many fathers who never had the opportunity to reunite with and engage in tickle fights with their children after the war and the end of slavery.

And then Lee was happy to break up families, separating mothers and fathers from their children, when he sold the enslaved at Arlington House.

There are several anecdotes about U.S. Grant as a doting father playing with his sons. I'm too lazy to go to my books on the one I most remember, but he would come home from work (I think this was in Galena, shortly before the war) and one of his boys would challenge him, and Grant would say something like "I am a peaceable man, but I will not back down to you!" and then the two of them would be wrestling on the floor. Might have been a better choice for a Father's Day article, but we all know that in the popular media, Lee tends t trump Grant. We almost have to remind folks about who surrendered to whom at Appomattox.