I’ve been eagerly awaiting Erik Larson’s new book, even more so this time around because his subject is the period between Lincoln’s election in November 1860 and the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861. This past Tuesday I headed over to pick up a copy of The Demon of Unrest at my favorite independent bookstore and dove right in.

It’s what you’ve come to expect from Larson. Rich character descriptions, colorful depictions of specific places, and a suspenseful narrative that keeps you turning the page. This one doesn’t disappoint even if you know how the story ends.

I am about 200 pages into the book. Normally, I wouldn’t share my thoughts until I’ve finished, but I’ve read enough to be able to comment on the author’s approach to narrating the slave experience.

This has already come up in two reviews. Here is Alexis Coe’s very negative review in The New York Times:

And still there was something lacking in the book’s 565 pages: Nary a Black person, free or enslaved, is presented as more than a fleeting, one-dimensional figure. Frederick Douglass, a leading abolitionist and standard of histories of the era, warrants no more than a mention.

Black people are primarily nameless victims of an antagonistic labor system that’s causing a political crisis among white Americans. At one point, to differentiate this near monolith, Larson employs the term “escape-minded Blacks,” a curious turn of phrase that suggests there were ‘bondage-minded Blacks.’

The flattening is all the more noticeable because so many other characters are given shape. Larson offers a cradle-to-coffin biography of the South Carolina congressman-turned-Confederate James Hammond. Lengthy passages on Hammond’s ‘five-way affair’ with (read: sexual abuse of) four teenage nieces are followed by a short, unnervingly euphemistic account of the enslaved women he (and his son) raped and impregnated: Hammond made Sally Johnson ‘his mistress,’ and when her daughter Louisa turned 12, he ‘made her his mistress as well.’

Larson’s magnolias-under-the-moonlight word choice is inadequate. Sally and Louisa were damned to Hammond’s forced labor camps, along with more than 300 enslaved people who ‘had a penchant for dying.’ But they got Christmas off, Larson notes; Hammond ‘held a barbecue’ and, on one occasion, ‘gave a calico frock to every female who had given birth.’

Adam Goodheart echoed these concerns in his much more favorable Washington Post review:

Black Americans are almost always treated as an unnamed, undifferentiated mass of passive victims: Although Larson unmasks the cruelty and hypocrisy of wealthy White enslavers, Frederick Douglass appears just once in the book’s 500 pages. Other Black activists, authors and strategists never do. Abolitionists (White as well as Black) are hardly mentioned, and then only as radical irritants to both sides whose inconvenient existence inflamed the tensions that led to disunion. In this sense, ‘The Demon of Unrest’ sometimes reads more like a product of the 1920s than of the 2020s.

These are legitimate concerns.

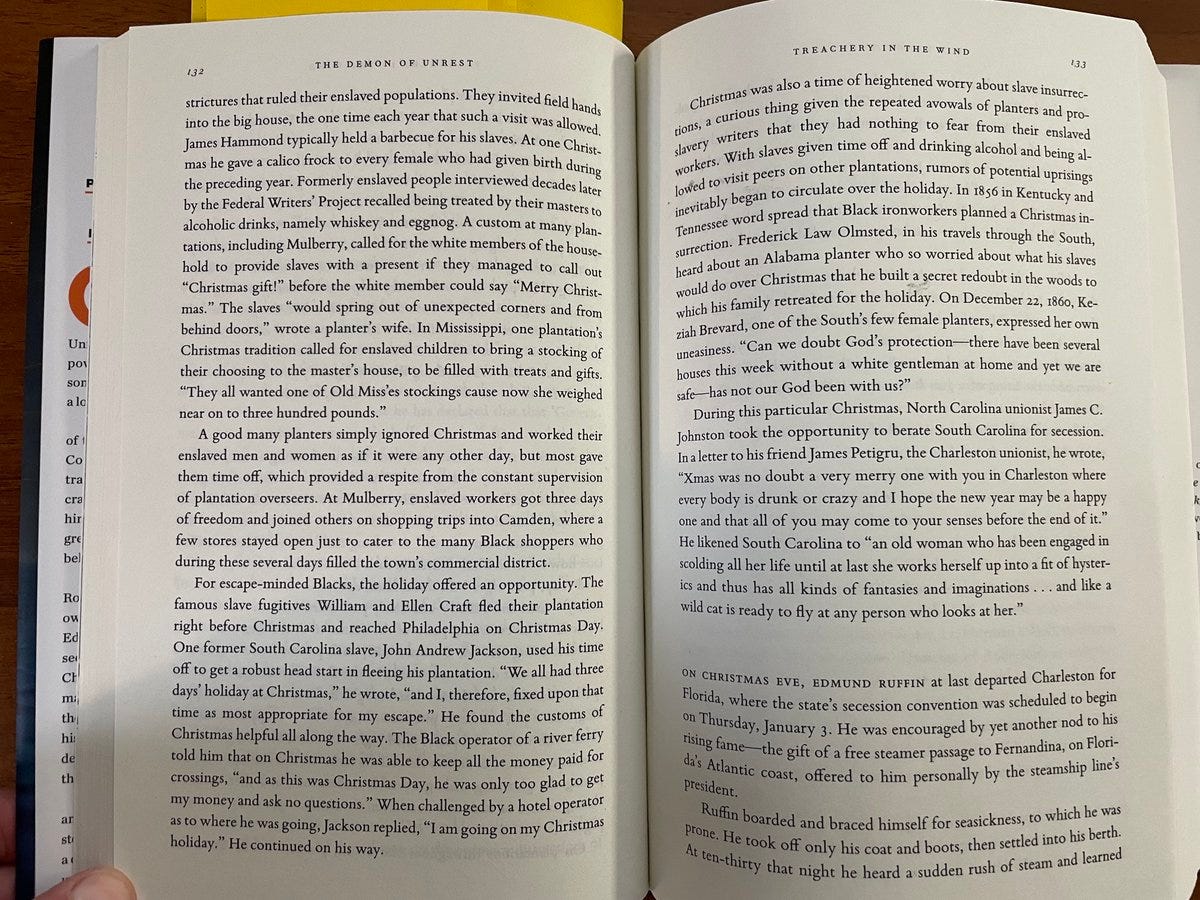

Here is the page in question that captures a number of Coe’s concerns. In it, Larson describes Christmas on Southern plantations. “On plantations throughout the South, planters briefly eased the…

Let’s be very clear, Larson is not a slavery or Lost Cause apologist. The author situates slavery at the center of the debates leading to Lincoln’s election, the secession of states in the Deep South, the formation of the Confederacy, and finally, the firing on Fort Sumter. He also acknowledges the violence of slavery.

The problem is that Larson allows slaveholders to narrate the experience of the enslaved. Unless you believe that slavery was the natural condition of Black people, all of them were“escape-minded” even if they never attempted to physically run away. Some enslaved people were given time off from their back breaking work during the Christmas season, but it was also a season that many people dreaded.

“Unfortunately, with all the attention given by memoirists and popular writers to elaborate Christmas partying on antebellum plantations,” writes historian Robert E. May, “it has been easy to overlook how much southern business activity persisted over Christmas, and the implications of this activity for slaves.” (p. 89)

Account books needed to be balanced, which often led to the sale of enslaved people and the fracturing of families to start the new year, to name just one example.

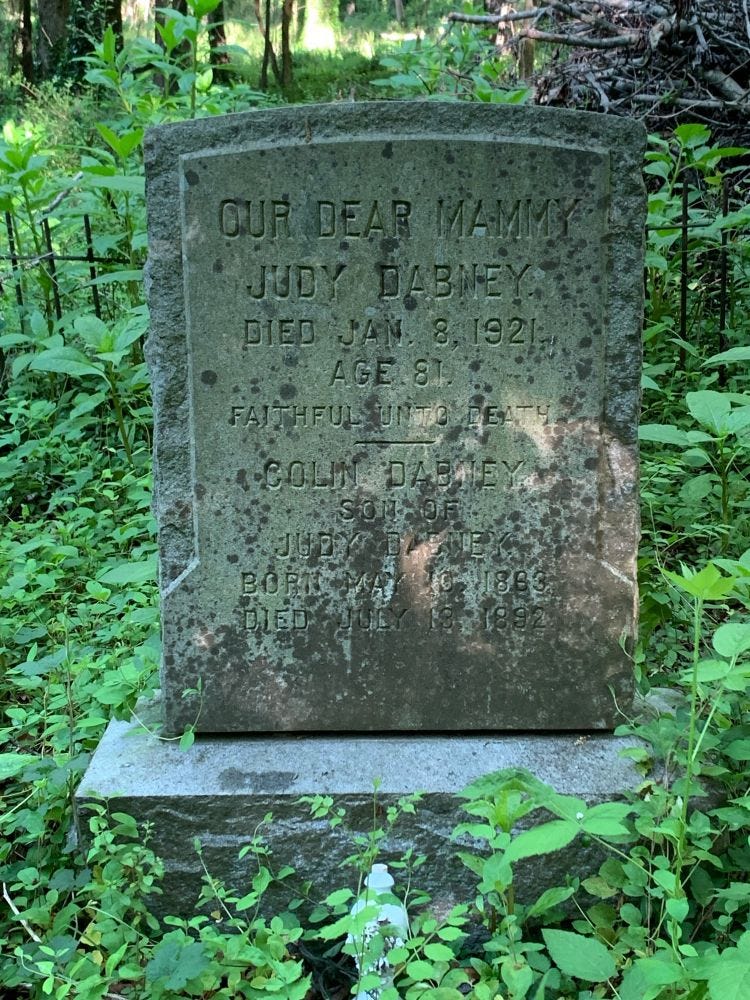

As May notes in his book, stories of the enslaved celebrating Christmas, along with their enslavers, became central in postwar narratives that became the bedrock of what he describes as “Dixie Lost Cause romanticism.”

These concerns are heightened, especially at a time when the nation is reckoning with its past, especially the history and legacy of slavery. The debate about monuments, textbooks, official holidays are as much about who gets to tell these stories as they are the content of the narratives themselves.

I can’t help but think that Larson missed an opportunity to add to the suspense of his story by helping his readers better understand what the events, that he describes so well in this book, meant to the enslaved. How did they view Lincoln’s election and the eventual firing on Fort Sumter and the coming of war?

That said, in the end Larson really isn’t interested in slavery and the experience of the enslaved. He is laser focused on the events that help to explain the eventual firing on Fort Sumter and he captures that in fine detail. He situates you inside Fort Moultrie as Major Robert Anderson contemplates moving his force to Fort Sumter in response to the growing threat from South Carolina and Washington, D.C., where President Buchanan desperately attempts to avoid conflict before his term ends and Lincoln assumes the presidency in early March 1861.

I am thoroughly enjoying Larson’s profiles of James Henry Hammond, Anderson, and especially Edmund Ruffin, but most of all and perhaps for the first time I’ve come to appreciate the contingency of it all.

Larson has likely written the most detailed account of the ‘secession winter.’ It offers and important reminder that there was nothing inevitable about war, even after the formation of the Confederacy in February 1861. Decisions were made that could have easily gone the other way, thus changing the course of history.

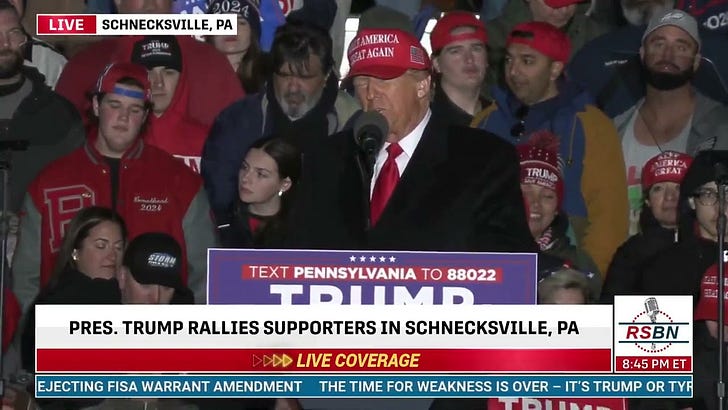

I suspect that many people, who do not know much about the Civil War, will finish reading this book wanting to learn more. That’s a good thing, especially at a time when so many in this country appear to be engaged in a collective fantasy about the possibility of another civil war. Perhaps it would be wise to first know something about the one that actually took place.

Are you and Dave Powell coordinating this effort to deplete my retirement accounts? <VBG>

I am going to attempt to defend Larson's choice of narrative, somewhat, which is kind of crazy because I don't even own the book (yet). The book appears to be intended to tell the story of what is commonly known as the "Secession Winter," and in that tale, the white enslaving oligarchy was driving the events in the South, thus they get the focus of the tale---it is, after all, men like Hammond and Ruffin who were driving events, so it is appropriate, even necessary, for Larson to focus on men like Hammond and Ruffin. This book appears to me to be the story of a contest between the white power structure in the North and the even whiter power structure in the South, and how they were unable (largely because the fire-eaters did not want it to happen) to reach an accommodation before war broke out. I *am* disappointed in the apparent minimal treatment of Douglass, because I am sure that the black population of the North had views on everything going on, and Douglass would have been an important voice for them. But the sad truth is that the enslaved population in the South had virtually no influence on events, THAT I AM AWARE OF. (If, in fact, they did have some influence, I'm totally unaware of it, and would love to be educated. Politely.) So I think the criticism of the author on this point is at least possibly a tad misplaced.

Thanks for your thoughtful essay (and replies to comments). I think I'll give this book a miss. While recognizing that you have read it and I haven't (important!), it sounds like too much is missing from Larson's account for me, particularly African American voices and experience. The resulting objectifying descriptions are also a turn-off (he sounds like he's talking about livestock, with his "Blacks" and "females"). I imagine, for example, that enslaved people were glad to escape not only the supervision of overseers at Christmas but also their routine violence. Whether either overseers or "masters" took a break from sexual violence over the holidays seems doubtful, especially for multiracial and -generational abuser and rapist Hammond. As to Southern honor, "Field of Blood" gives an outstanding description of how that worked in practice - does Larson acknowledge that reality or take the word at face value?

While one could argue that telling a political story requires only the voices of those empowered to speak in the political arena, it would be fair to readers to say so. Does Larson do that?

On that basis, however, one could argue for a history of the New York Married Women's Property Act that excludes detail about Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (outside their testimony). I wouldn't be interested in that either.

Nevertheless, I hope you enjoy the rest of the book as much as you have the first part.