Interpreting Confederate Slaves on the Gettysburg Battlefield

I am pleased to see that the Gettysburg National Military Park has begun to interpret the Confederate monuments that line Seminary Ridge or Confederate Avenue.1 These monuments—especially the Virginia monument (1917)—have long dominated the landsape of “Pickett’s Charge” have helped to reinforce many of the Lost Cause tropes associated with the battle and the broader war.

Interpretive markers are a welcome first step to addressing this as well as the current controversy surrounding Confederate monuments, though I don’t believe that they necessarily solve the fundamental problem that these monuments pose.

Still, I believe there is an opportunity to do some important interpretive work on the battlefield with these monuments. In recent years Gettysburg has attracted white nationalists, some of whom have embraced the battlefield’s Confederate monuments for ideological reasons.

Addressing the complicated and contentious history of these monuments is going to take a substantial commitment on the part of park historians, which will only happen if they get the financial and political support to do so.

Hopefully, at some point all eleven monuments along Seminary Ridge will be accompanied by an interpretive marker. Jill Titus’s new book on the centennial celebrations in Gettysburg digs deep into the Civil Rights and Cold War contexts for the monuments dedicated during this period.

The decision to begin with the North Carolina monument (1929) is a good one.

I agree with historian Scott Hancock that it would have been nice to see a reference to Borglum’s association with the Ku Klux Klan as well as his early involvement at Stone Mountain. I would have also appreciated a graphic (timeline) that situates the Confederate monuments at Gettysburg within the Jim Crow era, alongside the hundreds of monuments that were dedicated during this period in public parks and in front of courthouses throughout the South.

That said, I was very pleased to see the reference to slavery. In the future I would like to see this issue tackled more explicitly in connection to the battle itself. The North Carolina monument would be ideal for such a marker.

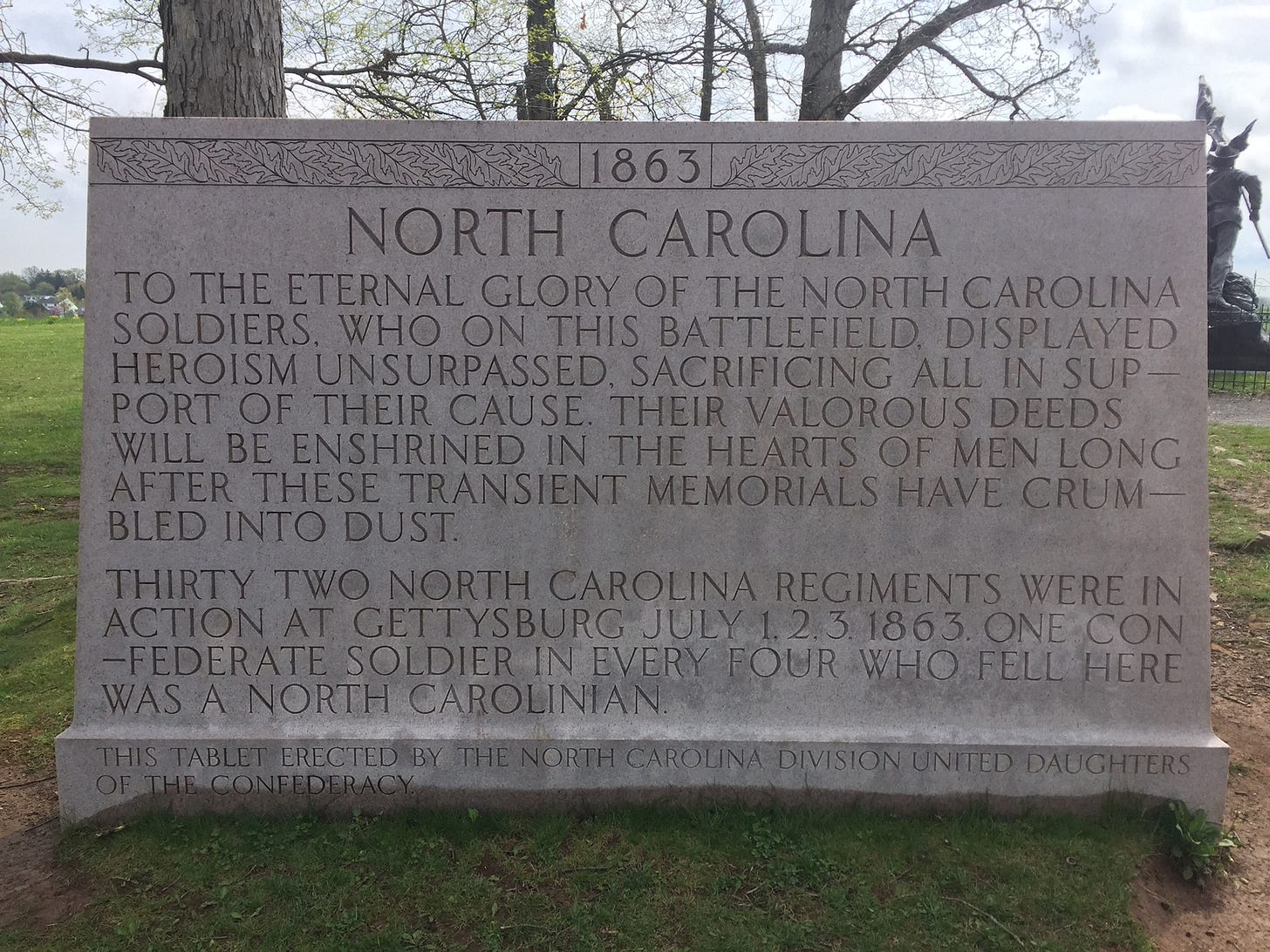

The accompanying large plaque situates the monument within the Lost Cause tradition by referencing the “heroism,” “glory” as well as the “sacrifice” of the North Carolinians during the 3-day battle. It offers a very helpful reminder of the important difference between history and memory.

The monument itself highlights the desperate and dangerous forward momentum of the North Carolinians during Lee’s final assault on July 3. It suggests that these men were committed to sacrificing everything to achieve victory. In doing so, it offers a one-dimensional picture of the rank-and-file. All were brave. No one fell short of the qualities of martial manhood on the battlefield.

What a visitor to the battlefield fails to appreciate, however, is that the very presence of the Confederate army in Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863 was made possible by thousands of enslaved man that accompanied the army.

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia likely included upwards of 10,000 slaves—what was essentially an army of slaves within an army. These men performed a wide range of roles as teamsters, blacksmiths, not to mention the thousands of body servants—or what I refer to as camp slaves—who accompanied their masters into the army.

Enslaved men were omnipresent throughout the battle. They kept men supplied on the front, came to the assistance of their masters when necessary, helped to evacuate wounded, among many other roles. Acknowledging these men in some way on the battlefield itself will go far in highlighting the deep disconnect between the history of the Confederate military’s reliance on slavery and the Lost Cause’s attempt to erase it from memory or by casting them as “loyal slaves.”

It also will help to address a tendency on the part of many who continue to argue that because the majority of Confederates did not own slaves they didn’t have any interest in maintaining or fighting for its preservation. Enlisted men certainly volunteered and continued to fight for a wide range of reasons, but acknowledging the presence of a large number of enslaved men in the army helps to make an important point.

Regardless of whether an individal soldier owned 100 slaves or no slaves at all, he was reminded on a daily basis of the importance of slavery to the Confederacy and he would have appreciated the extent to which the survival of the army and its opportunity to win battles like Gettysburg were made possible, in large part, by their very presence.

The preservation of slavery was not an abstract proposition for Confederates. By focusing on their military role at places like Gettysburg, we have a chance to truly appreciate the extent to which slavery functioned as the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy.

The reference to “Confederate Slaves” in this post’s title was coined by historian Peter Carmichael.

Really good information on this improvement at Gettysburg, thank you. And certainly there was room on the timeline for the information you referenced. Why on earth did Maryland put up a monument in 1984? Is there one for the Maryland Union soldiers? Smh