I never really thought that publishing a book debunking the Black Confederate myth would be my last word on the subject. This weekend I channeled my inner Michael Corleone (“Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!”) as I watched a clip from the new series Lawmen: Bass Reeves.

The series follows Bass Reeves (1838-1910), an African American lawman, who rises out of enslavement to become the first Black U.S. Deputy Marshal west of the Mississippi River. I don’t know much about his story. In fact, I never heard of him before last week.

We do know that Reeves was owned by Colonel George R. Reeves, a Texan sheriff, legislator, and one-time Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. Once the Cvil War broke out, George Reeves joined the Confederate army and Bass followed as his body servant or camp slave.

The opening scene in Lawmen depicts the two men in the midst of battle. Bass rides a horse and is wearing a Confederate uniform. A few other Black men can be seen among the rank and file as well.

Bass’s uniform will likely be confusing for some viewers, but I found plenty of examples of camp slaves wearing Confederate uniforms, usually provided by their enslavers. A uniform, however, did not magically turn an enslaved man into a soldier.

I should point out that at no point is Bass referred to or treated as a soldier by George or anyone else in the Confederate army. Even once the fighting begins and George decides to lead a charge against the enemy, he orders Bass to accompany him: “You will follow and you will fire.”

The statement reaffirms the master-slave relationship, but watching Bass kill two Union artillerists will no doubt add to the confusion for many viewers.

As in the case of enslaved men wearing Confederate uniforms, I also found numerous examples in the course of my research of camp slaves firing at the enemy, though I never came across an example of a cavalry charge.

What is important to remember here is that enslavers and Confederates generally were ambivalent about watching Black men brandish rifles against the enemy during battle. By displaying the same bravery as white men, their behavior threatened to collapse the master-slave relationship and the accepted racial hierarchy.

The battlefield was a racialized landscape on which white men were expected to display their bravery and defend their honor.

Unfortunately, the historical record is silent on Bass Reeves’s wartime experience.

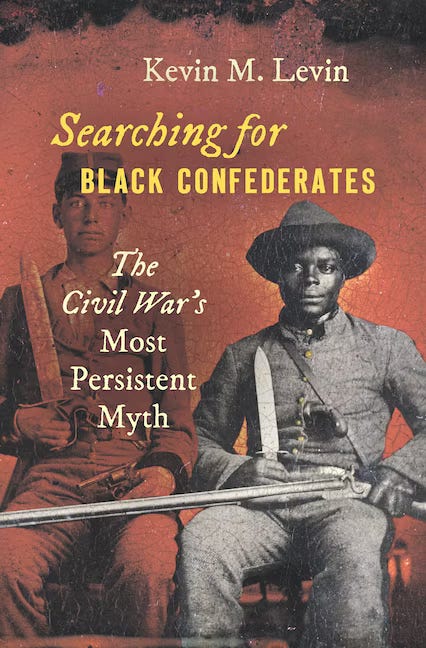

If you want to learn more about the ways in which enslaved men were utilized by the Confederate military and how these stories eventually morphed into the myth of thousands of Black Confederate soldiers, check out my most recent book.

Order from: Amazon / University of North Carolina Press / IndieBound

I did not know this part of the Bass Reeves story. He became an legendary lawman in territorial Oklahoma, battling outlaws both Black and white. In his last years, however, white authorities restricted Black lawmen, including Reeves, to only working in Black communities. There continued to be Black lawmen in Oklahoma--Sheriff’s Deputies, police officers, police detectives, etc., even the occasional Black Justice of the Peace (who in that time and place could try criminal cases, including felonies). But white lawmen were allowed to arrest both Black and white offenders, whereas Black officers were now, in practice, only allowed to arrest Black offenders. Some Black communities (I’ve studied pre-Massacre Black Tulsa) tried to use this restriction to their advantage and become completely self-policing.

I’ve known about Bass Reeves for quite some time and have always been impressed by his story. It is a shame that there is no record of him during the war. I have a copy of your book Kevin, it is excellent and I have used the information to inform occasional arguments regarding what the relationship was between camp slaves and the Confederate Army.