One of my all-time favorite history books is David McCullough’s The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge. McCullough wrote about the bridge as the central character of the book—as an extension of its architects, civic boosters, and the many workers who labored and even died during its construction. The book sparked my imagination and left me wanting to know even more.

From McCullough I learned that history could be exciting. I tried to capture this feeling in the quote I posted yesterday:

History, really, is an extension of life. It enlarges and intensifies the experience of being alive, like poetry and art or music.

This quote comes from an essay titled “Why History?” which was published in 1995. It is a theme that McCullough returned to regularly in subsequent years. The essay both reflects his love for history and the importance McCullough attached to history education as well as a belief that Americans had become woefully ignorant of the nation’s past.

We, in our time, are raising a new generation of Americans who, to an alarming degree, are historically illiterate.

The situation is serious and sad. And it is quite real, let there be no mistake. It has been coming on for a long time, like a creeping disease, eating away at the national memory. While the clamorous popular culture races on, the American past is slipping away, out of site and out of mind. We are losing our story, forgetting who we are and what it’s taken to come this far.

Warning signals, in special studies and reports, have been sounded for years, and most emphatically by the Bradley Report of 1988. Now, we have the blunt conclusions of a new survey by the Education Department: The decided majority, some 60 percent, of the nation’s high school seniors haven’t even the most basic understanding of American history. The statistical breakdowns on specific examples are appalling.

But I speak also from experience. On a winter morning on the campus of one of our finest colleges, in a lively Ivy League setting with the snow falling outside the window, I sat with a seminar of some twenty-five students, all seniors majoring in history, all honors students-the cream of the crop. “How many of you know who George Marshall was?” I asked. None. Not one.

At a large university in the Midwest, a young woman told me how glad she was to have attended my lecture, because until then, she explained, she had never realized that the original thirteen colonies were all on the eastern seaboard.

Who’s to blame? We are.

This assertion is premised on the belief that there was a time when Americans were significantly more knowledgeable about history. Even a cursory probe into the available evidence, however, suggests otherwise.

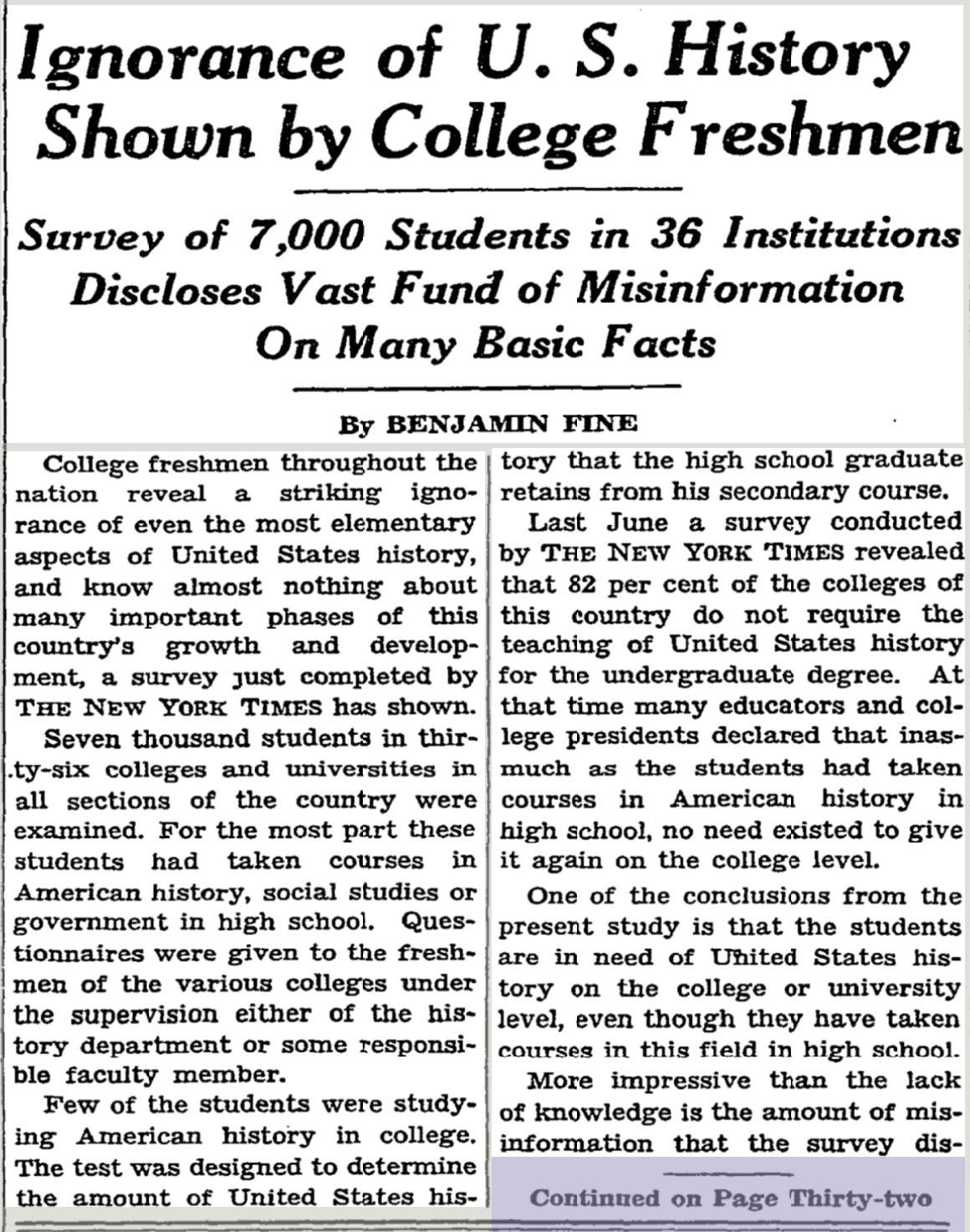

In 1943 The New York Times published a survey of college freshman throughout the nation and found them lacking in basic historical literacy.

I suspect that such results at the height of WWII, along with the need to keep the American people united along with the first signs of a Cold War with the Soviet Union led directly to the consensus history of the 1950s.

McCullough graduated from Yale in 1955. This consensus view shaped his writing, his choice of topics, how he understood the broad sweep of American history, and especially the civic importance he attached to history education.

In short, McCullough was a product of his time, who was never capable of stepping back and critically assessing the limitations of this consensus view.

Generations of Americans learned the Lost Cause narrative of the Civil War and Reconstruction as part of this consensus view. Their textbooks were filled overwhelmingly with white men. Women, African Americans, and other minorities appeared in supporting roles and always to help buttress an assumption of “American Exceptionalism.” Americans were taught that progress was inevitable and freedom and democracy would always push the nation forward.

McCullough’s subjects and narrative structure lent itself to this broad view of the American past. This is not intended simply as criticism, but to point out his limitations as a historian and what he achieved within this interpretive framework.

When McCullough warned his audiences about supposed student ignorance of history we need to acknowledge that it was the deteriorating influence of this consensus view of the past that he was mourning.

I have found over my twenty-five years of working with students that they are deeply interested in history and its importance for addressing many of society’s problems today. This more inclusive, more critical, and less celebratory view may have been a narrative of the past that McCullough found difficult to acknowledge since his 1995 essay, but that doesn’t make it any less meaningful or useful.

McCullough’s body of work is a significant achievement that will continue to introduce readers to the power and joy of history. And there is much to learn from him about the importance of history education.

At the same time, I celebrate the many voices that now occupy a space in the fields of historical scholarship, public history, and history education—voices that have long been blocked because of their gender, race, etc.

These voices have broadened and deepened our understanding of American history and forced us to confront questions and problems that have for far too long failed to attract the attention of more than a select few.

David McCullough was right…

History is for all of us.

A fitting eulogy to a great narrative historian. Alongside Sears, he was a worthy heir to a twentieth century narrative tradition often identified with Bruce Catton’s works, which are still worth reading for their superb literary quality alone. Rick Atkinson (a former journalist) is one of the few authors writing about history today who can claim a similar mastery of prose. While there are obvious limitations to narrative history, it remains one of the best ways to engage with the reading public, and offers anyone an opportunity to sit down and enjoy a conversation (that’s how these works often feel to me) with a master of the language.

Thanks, Kevin, for your interesting, nuanced comments on David McCullough. I think you've pinpointed both his strengths and his weaknesses.