When the Federal Government Hunted People in the Streets of Boston

Trump’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants earned the ire of the governor of Massachusetts, where in a similar case in 1854, the city of Boston fought to protect a runaway slave.

President-elect Donald Trump has spent the past two weeks selecting his nominees for various departments. Each pick is more bizarre and disturbing than the last one. None of them appear qualified for their respective positions and a few of them shouldn’t be allowed within 100 feet of our public schools.

But if there is one truly horrifying nominee or appointment in this cast of characters it is Tom Homan, who served as Trump’s acting head of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the first administration and who will now oversee border control.

Homan’s top priority will be the rounding up of undocumented immigrants on a scale that we have not seen in some time and he plans to use the military to do it. In response to the governors of New York and Massachusetts, who have stated that their respective states will not comply or assist with the federal government’s plan, Homan offered the following: “If you are not going to help us, get the hell out of the way ’cause we’re gonna do it. So, if we can’t get assistance in New York City, we may have to double the agents we send in New York City. We are going to do the job. Sanctuary cities are sanctuaries for criminals.”

This policy horrifies me, in part, because we have already seen the suffering and hardship that it can cause individuals and families looking for freedom and opportunity in the United States. In the 1850s cities like Boston were on the front lines of the federal government’s attempt to return fugitive slaves or “freedom seekers” to their enslavers.

I first wrote about this history back in 2017 for The Daily Beast, during the first Trump administration, which I am sharing with you today. The fear that I felt then is even more heightened today. I don’t make connections between the past and present lightly on this site, but this policy shouts out for historical context. This is a history that I regularly discuss with visitors to Boston on tours of Beacon Hill’s Black neighborhood, where hundreds of African Americans sought shelter and protection.

I will not look away.

In a press conference at City Hall last month, surrounded by elected officials and black, Latino, and Asian staff members, Boston’s Mayor Marty Walsh delivered a scathing response to President Donald Trump’s promise to crack down on illegal immigration through executive order.

“The latest executive orders and statements by the president,” argued Walsh, “are a direct attack on Boston’s people, Boston’s strength, and Boston’s values.” Walsh clearly had more in mind than simply reasserting the city’s commitment to preventing local police from reporting undocumented immigrants to federal authorities. Even at the risk of losing federal funding for much needed infrastructure projects, Mayor Walsh spoke for many in his commitment to protect Boston’s undocumented immigrants from being removed from their families and communities by federal authorities: “If people want to live here, they’ll live here. They can use my office. They can use any office in this building.”

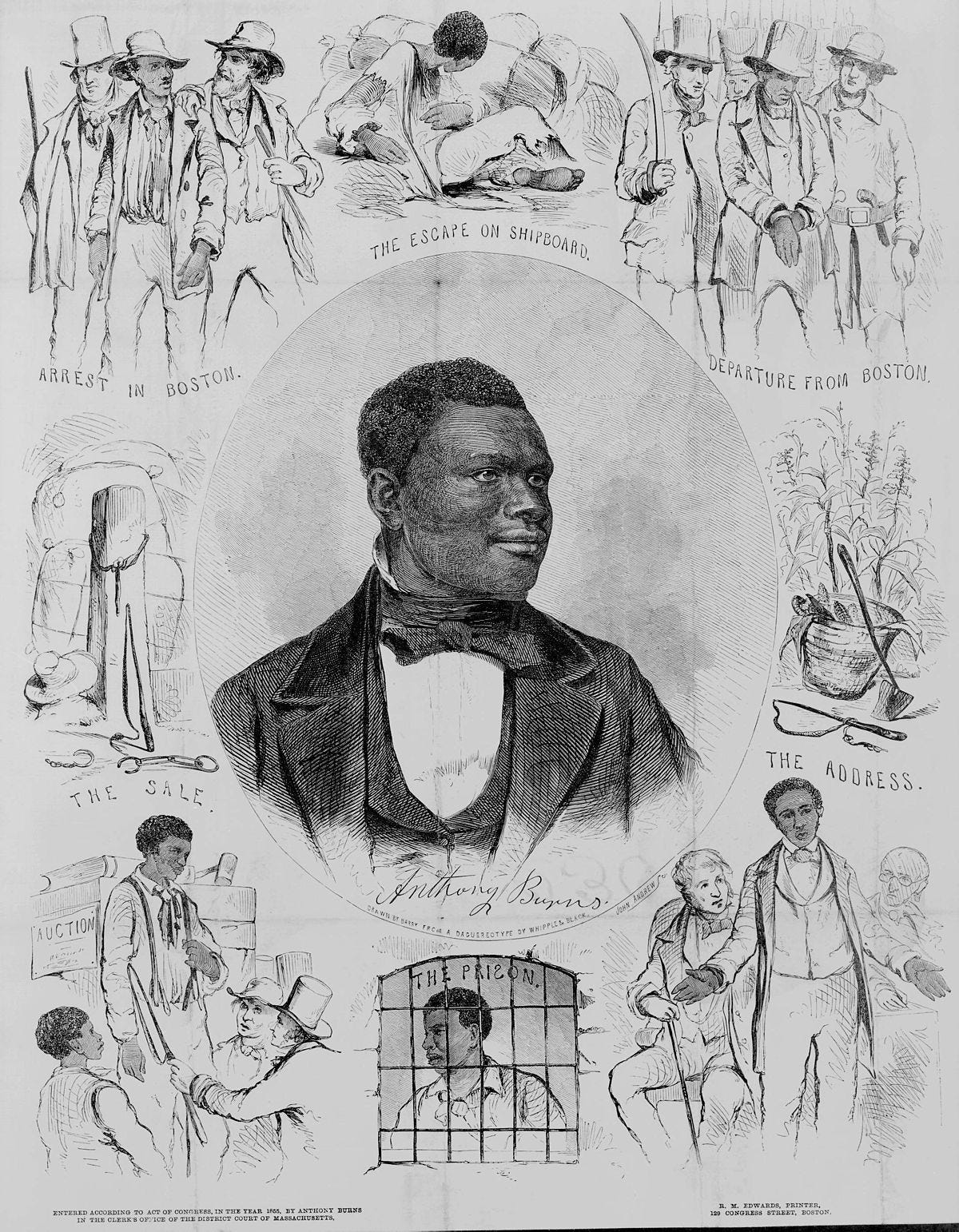

Boston is no stranger to standoffs with the federal government over individuals escaping hardship and seeking a better life in the city. Today it is undocumented immigrants, but in the 1850s the conflict centered on fugitive slaves from the South, who sought freedom and opportunity in Massachusetts. The most famous incident took place in the spring of 1854 and involved a fugitive slave from Virginia named Anthony Burns.

Burns had been enslaved since the age of 6 to Charles F. Suttle, a sheriff and shopkeeper in Alexandria, Virginia. Suttle eventually hired Burns out to a pharmacist in Richmond. While in Richmond, Burns used his free time to earn extra money, make the necessary contacts on the city’s wharves, and plan his escape with a Boston-bound sailor.

In early February 1854, he arrived in a city deeply engaged in the debate over the future of slavery in the United States. Boston was the home of a vocal community of black and white abolitionists that included William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the controversial newspaper The Liberator.

In Boston, Burns secured temporary employment as a cook and window-cleaner before finding long-term employment at a clothing store. He might have been able to make good on his escape, but for a letter that he mailed to his brother in Richmond, which was postmarked from Canada to conceal its origins but dated from Boston. The letter was discovered by his brother’s master and shared with Suttle.

On May 24, 1854 Burns was arrested by deputized agents of the U.S. government and promptly removed to the federal courtroom, where he was locked in the jury room and forced to face his former master. Suttle took advantage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which was signed into law by President Millard Fillmore as part of the Compromise of 1850, a series of laws intended to end sectional strife over the expansion of slavery into the western territories. The law made it easier for slave owners to recover slaves who fled to free states by requiring the former to secure a sworn statement or document certifying that appropriate testimony had been given to an official in the state from which the alleged escape had occurred. Once the document was provided, the federal commissioner was bound by law to issue a certificate that allowed the owner to transport his slave back home.

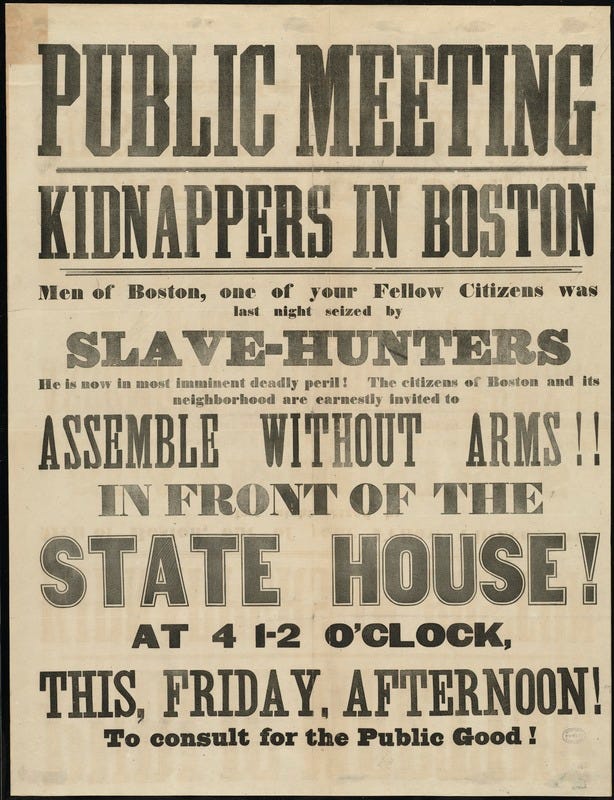

This was not the first time the Fugitive Slave Act was invoked in Boston. Residents of the city foiled an attempt in 1850 to recapture fugitive slaves Ellen and William Craft. That same year, in a more high-profile case, Bostonians stormed the courthouse and rescued Shadrach Minkins, who was dangerously close to being transported back to Norfolk, Virginia. The unrest and violence from these earlier incidents led to stricter measures that would eventually help to secure Burns’s fate.

As lawyers for the two parties prepared for trial, the streets of Boston were awash in plots to rescue Burns from the courthouse. Following a meeting at Faneuil Hall on the evening of May 26, a Vigilance Committee, led by abolitionists Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Lewis Hayden attempted to storm the Court House. Higginson gathered an assortment of weapons and stirred up the crowd with inflammatory language announcing that “a large number of negr**s were assembled at Court Square,” waiting to rescue Burns. The crowd broke down the Court House door with a beam that they turned into a battering ram. Shots rang out on the first floor, but the rescue attempt ultimately proved unsuccessful. At some point in the melee James Batchelder, who was serving as a temporary deputy federal marshal, was hit by a bullet and killed.

The next morning Burns’s lawyer Richard Henry Dana noticed the courtroom “was filled with hireling soldiers of the standing army of the U.S.... ready to shoot down good men, at a word of command.” In addition, U.S. marines from the Charleston Navy Yard and Fort Independence were ordered by officials to secure the trial site. Boston’s mayor, Jerome Smith, made his position clear to the city by calling out the militia. President Franklin Pierce followed events closely in the nation’s capital and signaled his support to the federal marshal in Boston: “YOUR CONDUCT IS APPROVED. THE LAW MUST BE EXECUTED.”

While local and federal troops maintained an uneasy peace outside the courtroom, lawyers for Burns and Settle pleaded their respective cases. Dana’s case was hamstrung from the beginning owing to a conversation that took place between Burns and Settle that acknowledged the legal relationship between the two. Testimony from witnesses corroborated the conversation, which is all the prosecution needed to prove its case. Dana and his co-counsel attempted to argue that the Fugitive Slave Act was unconstitutional and that their client was not the person who escaped from Virginia, but neither believed that these arguments would prove convincing to the judge.

Throughout the trial the city remained on edge with demonstrations organized by groups from within and beyond Boston. Five hundred black and white members of the Worcester Freedom Club descended on Boston on May 29, marching two abreast to the now fortified Court House. The Liberator noted that their appearance “created some excitement” among the crowds, “who cheered them with a will.” More ominous were the letters received by Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker from a “friend of the slave” in New York suggesting that an attacking force carrying “ten pounds of chloroform” could subdue the Court House guards. Newspapers only added to the concerns among local and federal authorities. The Boston Evening Transcript reported that 1,000 pistols had been sold to black men for the purpose of rescuing Burns.

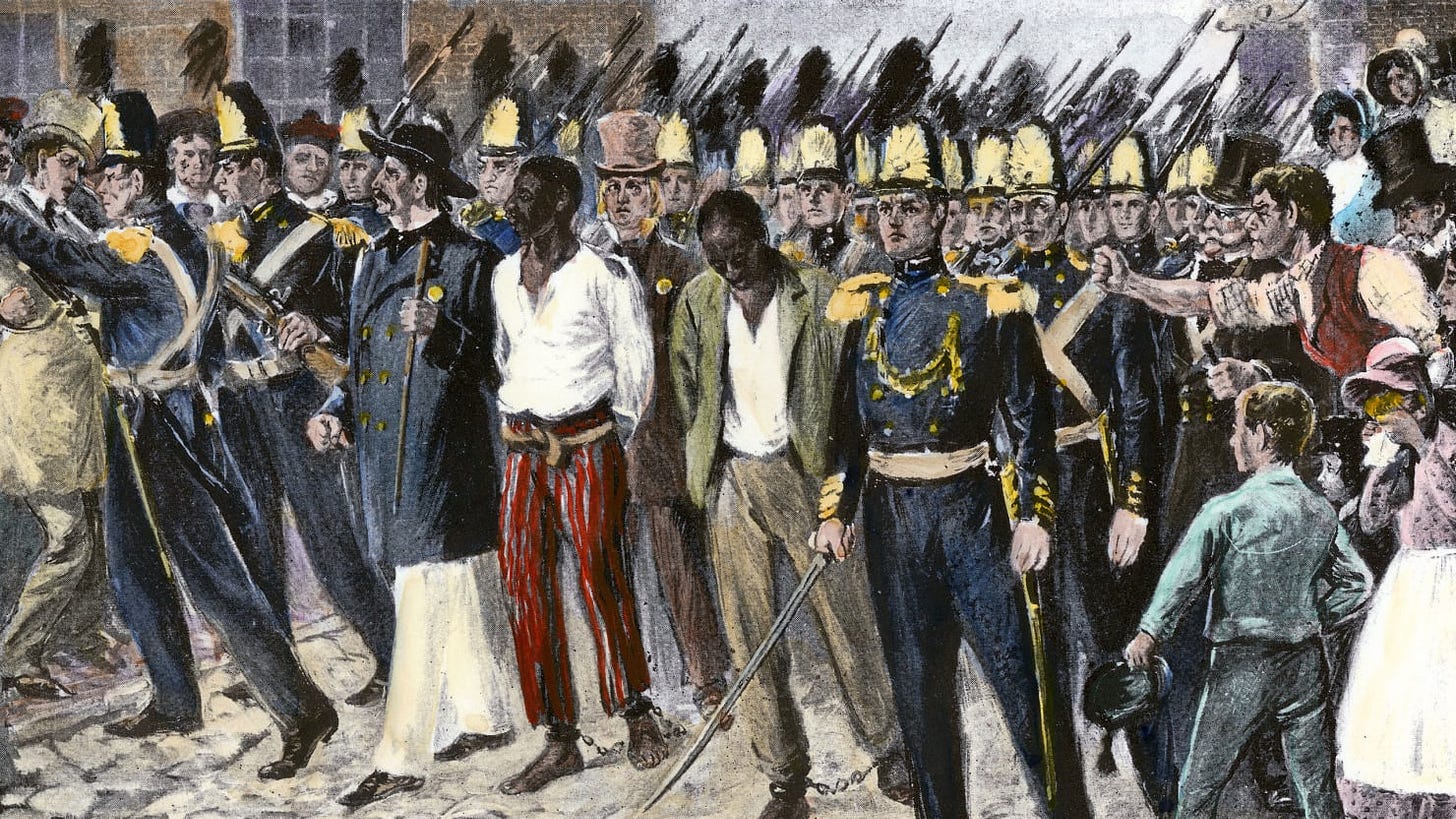

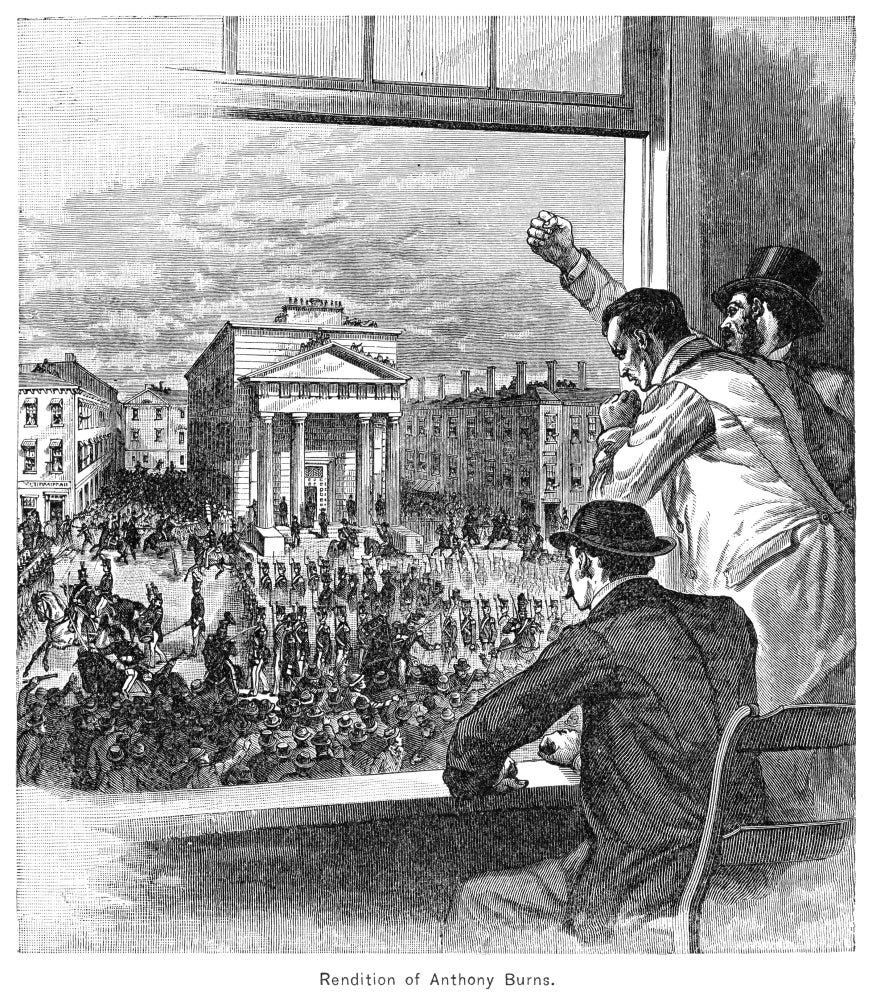

Evidence of popular outrage over the trial continued right up until its final day on June 2. The federal marshal in charge prepared for the worst, asserting that, “if bloodshed is to be prevented in the public streets, there must be such a demonstration of a military force as will overawe attack.” Secretary of War Jefferson Davis ordered the Army’s adjutant general to Boston to help maintain order and to transfer Burns back to Virginia on a naval vessel if necessary. By 7:30 a.m., a detachment of the Fourth Regiment, U.S. Artillery was ordered to the front of the Court House with one cannon. Soon thereafter the mayor issued a decree warning citizens “to leave those streets which it may be found necessary to clear… and, under no circumstances, to obstruct or molest any officer, civil or military, in the lawful discharge of his duty.”

Judge Edward G. Loring announced his ruling in favor of the plaintiff at 9 a.m. All that was left to do was transfer an utterly dejected Burns the third of a mile from the courthouse to Long Wharf. In one final act of defiance Boston police captain Joseph Hayes resigned rather than have to order his men to help return Burns to slavery. Shortly thereafter, Burns, wearing a suit and blue silk handkerchief chosen by his captors, left the courthouse in the middle of a square of 120 “specials” armed with revolvers. Burns refused to be shackled for the first leg of his journey back into slavery.

Burns’s return to Virginia was only temporary. After he was sold to a North Carolina slave trader, his freedom was purchased by Leonard Grimes, a Baptist minister in Virginia. Burns returned to Boston in 1855 and traveled throughout the North to share his story. He eventually became the pastor of Zion Baptist Church across the border in Canada. He died in July 1862, just a few months shy of the signing of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The same year that Burns returned to Boston the state legislature passed “An Act to Protect the Rights and Liberties of the People of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” which defied the authority of the federal government by preventing the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act within its borders. No fugitive slave was ever returned to bondage from Massachusetts following its passage.

There are echoes of Boston’s response to the arrest and trial of Anthony Burns in the mayor’s renewed commitment to the city’s undocumented immigrants. It is highly unlikely that the current standoff between the city of Boston and Washington, D.C. will escalate to the level of tension seen in the spring of 1854, but it is a reminder of the passions that can be stirred in our communities when the most vulnerable and those living on the periphery of society are no longer able to enjoy the freedom and opportunity that many of us take for granted each and every day.

Sitting in my car (parked of course) with tears. Thank you for reminding me of the strength on Bostonians. I had never read this story but have lived here for decades.

Wonderful essay on Burns! These stories are good preparation for the next four years of vicious, imbecilic, racism as spat out by the like of Homan....

But then, "Leonard Grimes, a Baptist minister in Virginia" stopped my reading to paste into the search engine. (IDK why!) Found this 2.5 page biographic paper: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/559ec31fe4b0550458945194/t/563e32d7e4b0f9aa57e4e556/1446916823148/lgrimes.pdf

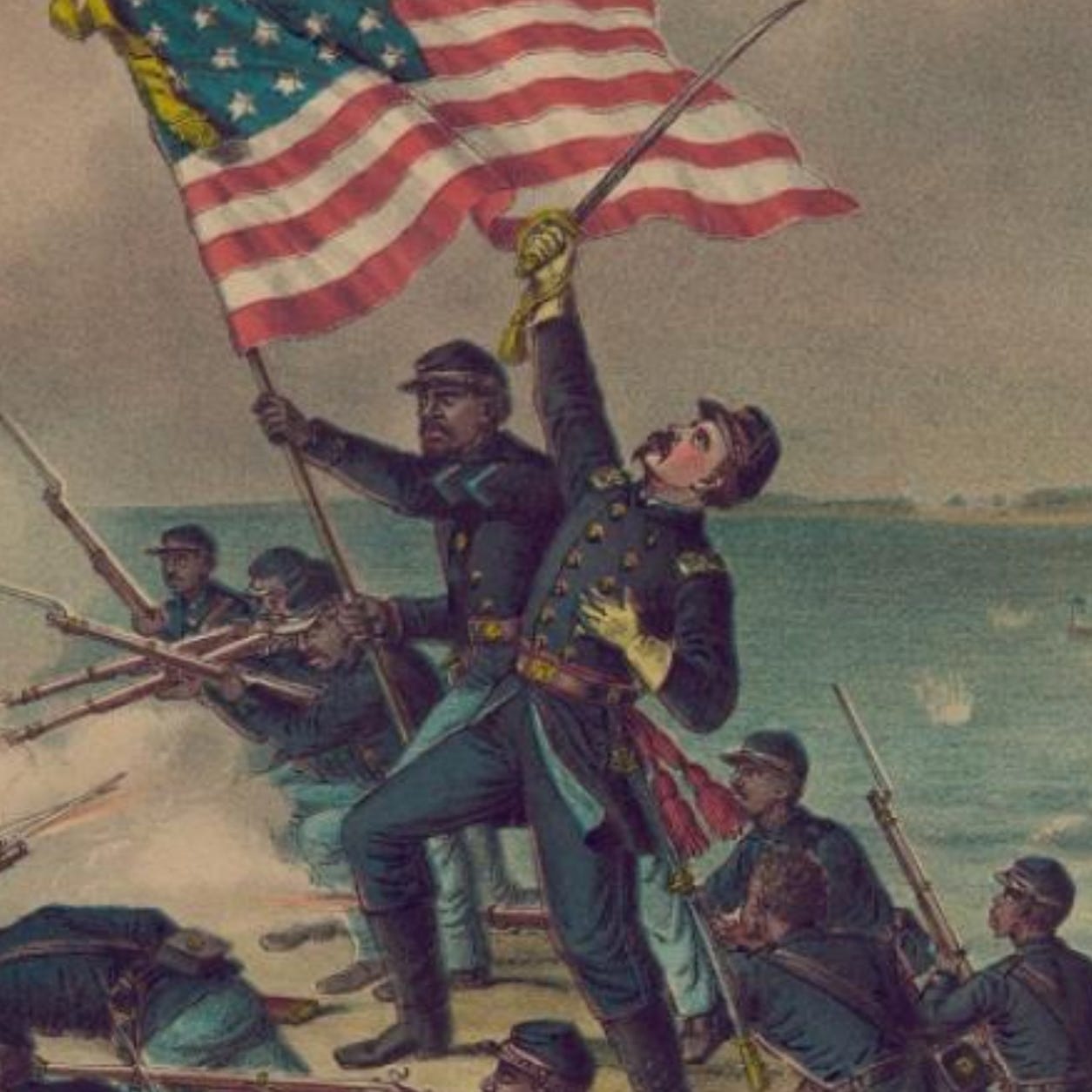

That Grimes and Burns were linked seems inevitable yet just looking at the remarkable life of either testifies to how second-class Americans then and now have their versions of La Migra to fear and fight. Grimes in his earlier days ran a hackney service as a front for his using it as an Underground Railroad line. Caught once and convicted for helping a family escape north, he had the 1840s Dream Team legal defense and got "only" a minimum sentence of 2 years in state prison + $100 fine. It wasn't time wasted: he "got religion" in lockup. Upon release, he moved to New Bedford with his family. He studied for the ministry and headed the new 12th Baptist Church in Boston. He turned it into an Abolitionist power center. After Burns lost his freedom, Grimes raised the money to buy his freedom. He recruited for the 54th Regiment and was offered its chaplaincy but remained at his church post.

Back to reading KML's meaty post.