The day after my cousin perished in the South Tower of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, I was back in the classroom trying to help my students process what we all had just experienced. Emotions were high and there were plenty of tears. I did everything in my power to hold my tears back until the end of the day. In addition, there was a good deal of fear and a palpable sense of the unknown pervaded my classroom for the next few weeks.

More than anything else, my kids wanted me to assure them that it was all going to be OK. I did my best to do so as any caring adult would try to do, but as a history teacher I knew better.

There is nothing about my knowledge or work as a historian that gives me any kind of privileged access as to what the future holds and as history teachers I think we have a responsibility not to use our classrooms to try, especially in a moment like this.

This is true today as much as it was true on September 12, 2001.

What we can do is use the present moment to help our students think more critically and deeply about the past. One way we can do this is by emphasizing the importance of contingency in history—the idea that historical events are not predetermined, but are instead the result of a combination of factors, including chance, human decisions, and earlier events.

A historian friend of mine captured this in a post he wrote this morning on Facebook: “It's an opportunity to capture the euphoric restlessness of not knowing the future.”

I couldn’t agree more.

There was nothing inevitable about the attack on our nation on 9-11 and there was nothing inevitable about the results of the election last night. Events could have turned out different.

Appreciating the contingency of the past, along with our own feelings of confusion, uncertainty, and fear, place us in good company with those who came before us.

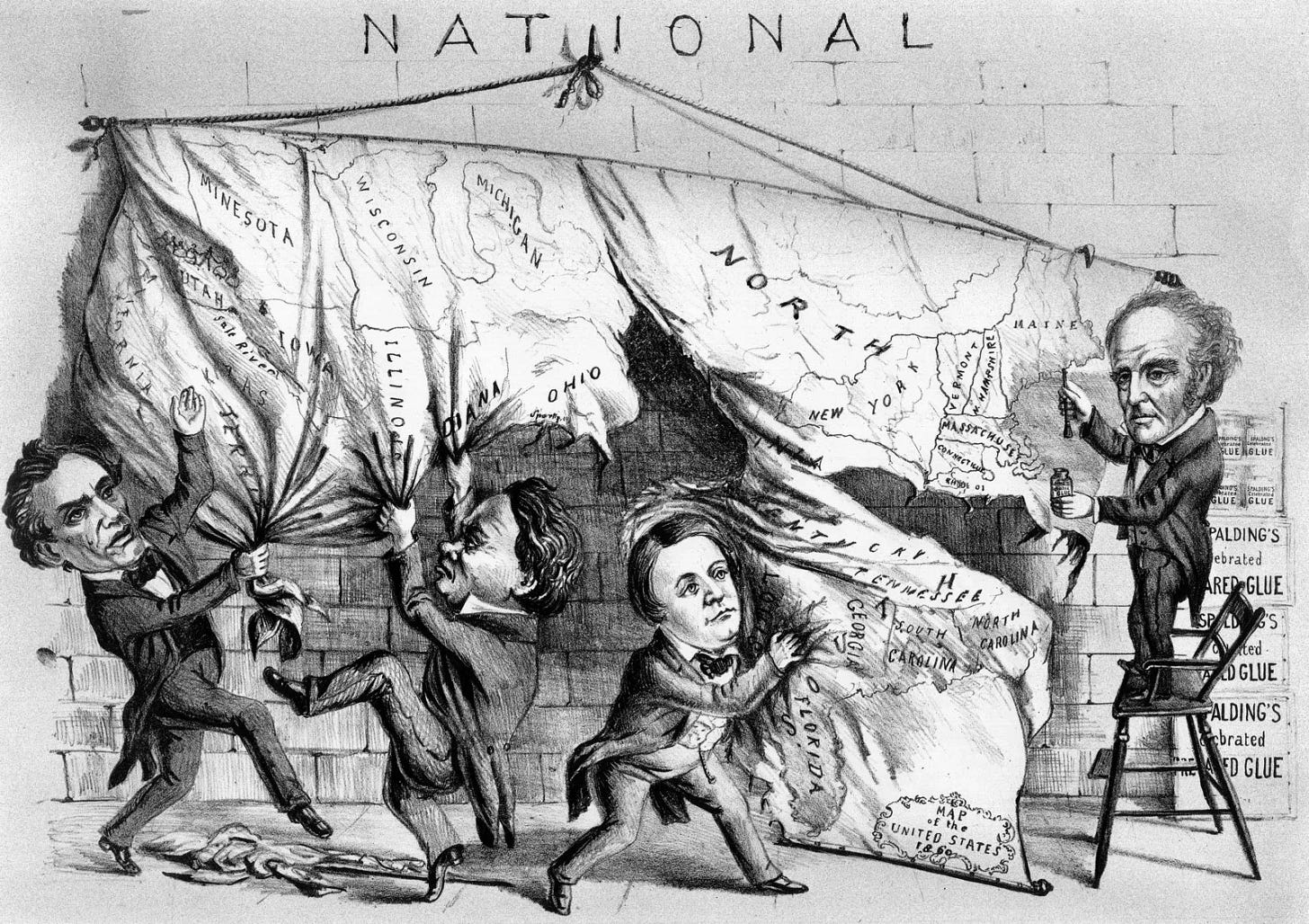

As a historian of the Civil War era I can’t help but think about the ways that Americans attempted to process the presidential election of 1860 and the prospect of war or Lincoln’s uncertainty about whether he would be reelected in 1864. Then there is the end of slavery and freedom for four million people. Nothing was inevitable about these turn of events and nothing that followed was inevitable. Events could have taken any number of turns.

I recently came across this letter that Charles Sumner wrote to the Duchess of Argyll on March 19, 1861.

I wish that I had something pleasant to write with regard to our affairs. There is a lull for the moment; but the future is uncertain. Thus far in a most remarkable way events have been so tempered & restrained, as to avoid bloodshed. Can this be always? I hope so; but I am not certain.

Our new Administration comes to power at a moment of unprecedented difficulty. But beyond this, it has an awkwardness, which is partly attributable to its inexperience. I trust, however, that, it will shew itself able to lead with events as they occur.

Of course, acknowledging the contingency of the past does little to alleviate the feeling of uncertainty and fear in the present moment. Nothing can do that, but appreciating contingency also has the potential to spur people to action in the present by reminding us that the future is not set in stone.

Well said Kev....Dad