West Point's Robert E. Lee Problem

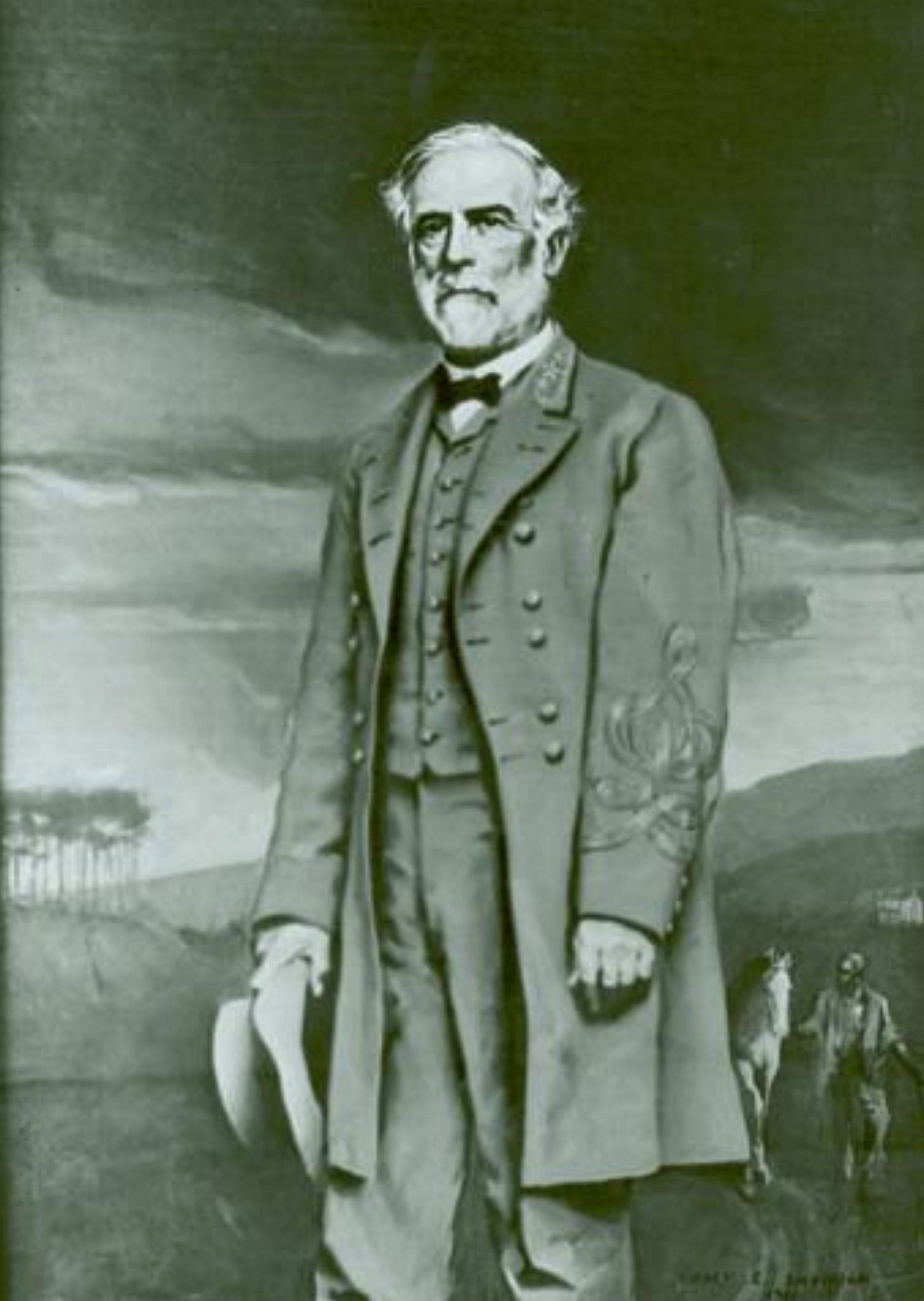

This past week Politico reported that the Naming Commission tasked with recommending new names for military bases that honor Confederate leaders will also recommend that West Point remove a portrait of Robert E. Lee depicted in his Confederate uniform. The painting has hung in the school library since 1951.

Robert E. Lee was a graduate of West Point and superintendent of the school from Sept. 1, 1852, to March 31, 1855. Lee resigned his commission in the United States Army following the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861 and took command of Virginia military forces before emerging as the Confederacy’s most successful general.

The question of whether Confederate graduates of West Point deserve to be honored has divided the academy in much the same way that this issue has divided the general public over Confederate monuments and memorials. A closer look at West Point’s Robert E. Lee problem reveals a complicated history and a reminder that these debates are almost always about the evolution of memory rather than simply about history.

Ty Seidule covers this issue thoroughly in his wonderful book, Robert E. Lee and Me, which explores his own personal journey of coming to terms with the legacy of the Lost Cause and Robert E. Lee.

We should start by acknowledging that—with few exceptions—neither Lee nor the Confederacy were honored at West Point during the nineteenth century. According to Seidule:

The Civil War became the greatest crisis in the academy’s history, just as it was the greatest crisis in the nation’s history. In 1861 and 1863, Congress debated bills to close West Point completely. While those bills failed to muster a majority, they left a lasting impression. West Point refused to memorialize Lee and the men in gray in the nineteenth century because Congress and the nation blamed the academy for its graduates’ decision to fight agains the United States. (p. 185)

This began to change in the new century, following the Spanish-American War, and as an expression of sectional reconciliation. In 1902 former Confederate general James Longstreet was invited to take part in West Point’s centennial celebration, largely, according to Seidule because after the war he joined the Republican Party and “endorsed biracial politics.”

It was not until 1931 that West Point honored Robert E. Lee with the help of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The UDC first donated three glass cases to be filled by plaques honoring the annual winner of the Robert E. Lee prize in mathematics.

The second was a painting depicting Lee in his U.S. Army lieutenant colonel’s uniform during his tenure as superintendant of the academy.

The UDC wanted the portrait to show Lee wearing the uniform of the Confederate States of America, but the army’s chief of staff refused to countenance a portrait of Lee in gray at West Point. The army would allow Lee to be honored for his time in blue, but not yet for his leadership in a rebellion. (p. 193)

Seidule credits this change as reflecting Lee’s improved reputation among white Americans as well as Jim Crow segregation. It was no accident that the UDC’s welcome coincided with the return of the first African-American cadets in roughly fifty years.

Twenty-years later the portrait that is currently in the spotlight arrived at West Point. Secretary of the Army Gordon Gray, a North Carolinan, ordered that the painting be hung to “symbolize the end of sectional difference” following World War II. The portait of Lee,” writes Seidule, “shows him resplendent in his formal gray uniform with yellow piping on the sleeve and three stars in a wreath on his collar, designating a general of the army of the Confederate States of America.” (p. 197)

Seidule argues that the placement of the painting in 1951 had everything to do with tensions over race relations.

The Korean War raged in 1950. At the same time, the army tried to slow roll implementatin of racial integration ordered by Harry Truman on July 26, 1948, in Executive Order 9981. The military has trumpeted its role in bringing racial equality to America, but the history is far more complex and less flattering. Neither uniformed leadership nor Gray wanted to integrate the army. In fact, the previous secretary of the army, Kenneth Royall, had been forced into retirement because he would not integrate quickly enough. Only the personnel requirements of the Korean War forced the army to integrate. Segregated units wasted manpower. (pp. 197-98)

Sidney Dickinson, born in Connecticut and trained in New York City, was given the commission to paint Lee. He chose to base his portrait on a photograph of Lee taken by Matthew Brady in Richmond following his surrender at Appomattox.

Interestingly, Dickinson painted African Americans while living in Alabama in 1917 and 1918, but chose not to depict them through the lens of racial stereotypes or the Lost Cause tradition.

This seems to stand in contrast to how Dickinson depicts what appears in the background of the Lee portrait to be a body servant. Seidule believes that Dickinson intended to portray “an emancipated man, not an enslaved servant…moving toward an uncertain but free future. Lee and the slave economy he fought to protect and expand diminsh like the setting sun.” (p. 199)

Seidule may be right about this, but it looks to me like the Black man is following Lee with his horse Traveller. If he is emancipated he clearly embodies the Lost Cause trope of the “loyal slave”—even after freedom, former slaves remained loyal.

The painting is located in the academy’s library on a wall opposite a portrait of Ulysses S. Grant.

The Naming Commission’s final report and recommendations will not be released until October of this year. In the meantime, West Point officials have suggested that they may devise a plan of action based on examples where Lee is honored for his time as a U.S. Army officer and role as superintendant v. his time in the Confederate army.

Regardless of how this turns out, we need to keep in mind that this question/debate has much much more to do with institutional memory than anything having to do with history. It took close to seventy years following the Civil War for West Point to include a painting of Robert E. Lee and another twenty to see him depicted in a Confederate uniform.

Even a cursory review of the relevant history suggests that removing this portait of Lee has about as much to do with ‘erasing history’ as the decades in which West Point stood steadfast against honoring former Confederates at all.

The only question that matters is whether the leadership at West Point believes that Robert E. Lee embodies the values that it expects graduates to uphold while serving our country.

Thank you for bringing Ty Seidule’s informed opinion to this discussion. For those who don’t know of him, Seidule is a “retired United States Army brigadier general, the former head of the history department at the United States Military Academy, the first professor emeritus of history at West Point, and the inaugural Joshua Chamberlain Fellow at Hamilton College.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ty_Seidule And one of four representatives of the US Department of Defense to the Naming Commission. Like me he is a Virginian and like me he is recovering from a lifetime devotion to the hateful lost cause. Amazing that we could say “lost” with such pride, isn’t it? You’ve lived in Virginia, and you know.

You have taught us to look for the dates on any rebel memorials, so I knew 1951 was suspect when first reading about this. And I agree with you completely about the Black man leading what appears to be Traveler (what other house could it be if that color?).

Another great and timely letter - Chag Sameach!

Excellent read.