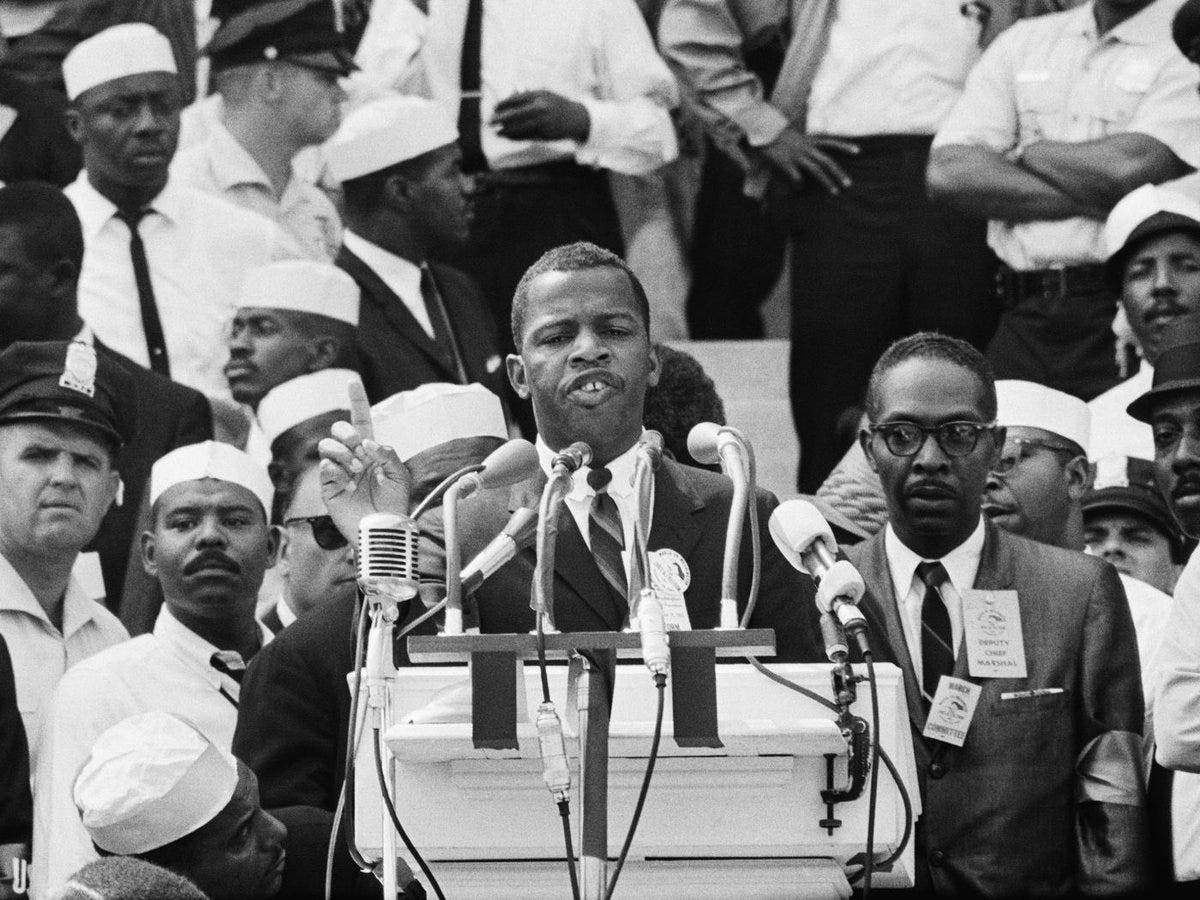

Few people remember the former student leader of SNCC and Georgia congressman John Lewis’s speech from the March on Washington rally, which took place 60 years ago today. Like most speeches delivered that day they were eclipsed by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s visions of a dream that “one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

No one remembers the following passage in which Lewis referenced “Sherman’s March”:

We won’t stop now. All of the forces of Eastland, Bamett, Wallace and Thurmond won’t stop this revolution. The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently. We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy. We will make the action of the past few months look petty. And I say to you, WAKE UP AMERICA!

That’s because Lewis was forced to excise it from his speech out of concern that it would offend and alienate white America and especially white southerners. The memory of Sherman’s March was still felt viscerally by many in the South. The 1939 Hollywood blockbuster, “Gone With the Wind” beautifully captured the fall of Atlanta and the indiscriminate destruction that ensued in the army’s “march to the sea.”

John Lewis no doubt understood how his words would be interpreted by white southerners. His appropriation of this narrow slice of Lost Cause lore was intended not simply to unsettle his audience, but to announce that African Americans would continue to demand full civil rights and work towards a true biracial democracy, regardless of whether white America was ready.

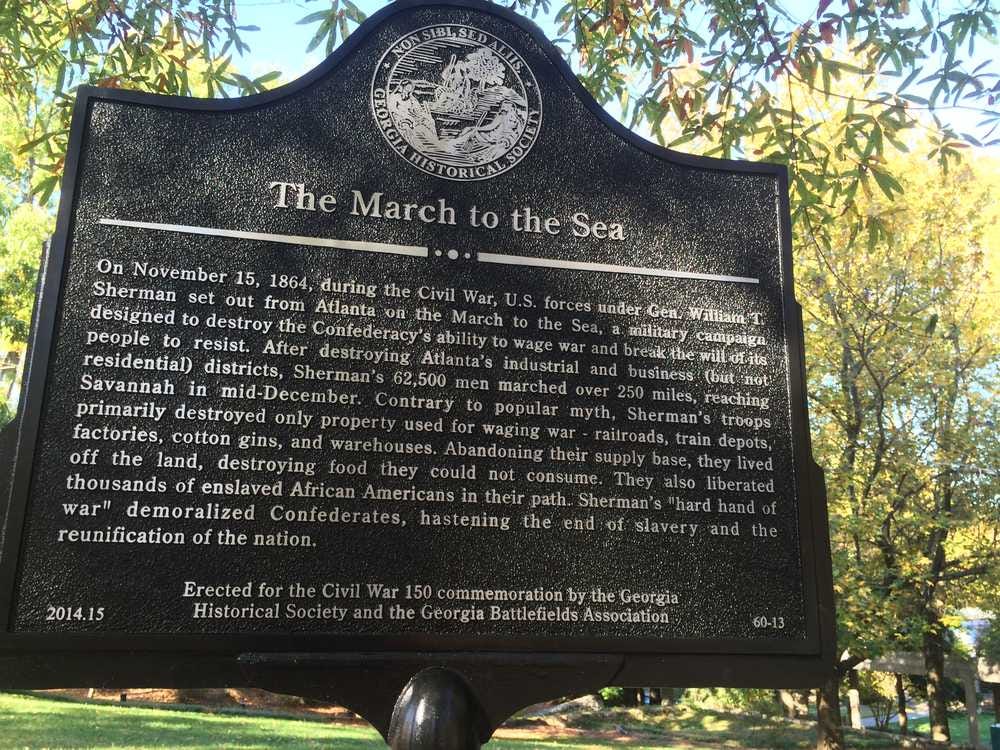

Sherman’s March remains clouded in myth even today. Historians such as Anne Sarah Rubin have challenged long-standing beliefs that Sherman’s men engaged in indiscriminate plundering and murder during their march to Savannah. The Georgia Historical Society has worked to educate the public with new historial markers.

Certainly there was a great deal of destruction, but despite accounts that demonstrate that soldiers strayed from Sherman’s directives on occasion, we now know that it was largely focused on the Confederacy’s military infrastructure. In short, it was targeted destruction.

It is difficult to appreciate just how shocking the sight of an angry John Lewis invoking the memory of Sherman would have appeared to much of the nation in 1965—the final year of the Civil War Centennial.

The centennial largely revolved around a Lost Cause/Reunion narrative that was intended to appeal to white America. It constituted a consensus narrative that would maintain national unity at the height of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

During the first few years of the anniversary, the Civil War Centennial Commission steered clear of the divisive subjects of slavery and emancipation. The Confederate battle flag went up atop the state house in Columbia, South Carolina. The state of Georgia itself reconfigured its state flag to include the Confederate flag. Battle reenactments and other events that spoke to a shared heritage of white northerners and southerners occupied the attention of the country, but by 1963 it became more and more difficult to ignore the “unfinished work” of emancipation and the end of slavery.

King himself capitalized on this historical amnesia in the opening two paragraphs of his address in D.C.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check.

Both Lewis and King were reclaiming Civil War memory in their attempt to steer the nation toward a new beginning on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Both men understood that history and historical memory needed to be torn down and reimagined. America had embraced a false memory of the Civil War and of African Americans specifically. The nation had forgotten the role that African Americans had played in saving the nation and destroying slavery forever.

It was an opportunity to infuse the rally in Washington and the Civil War Centennial with an “emancipationist” memory of the Civil War.

Americans needed a history lesson in the shadow of Lincoln that day and 60 years later many of us still need to come to terms with this past.

After making great strides in combatting racism in the USA .From the outside looking in it seems to of stagnated or even gone backwards .

With the election of Obama it seemed as it the corner had been well and truly turned .Since his term of office ended it seems that you as a nation are going backwards on this.

I maybe wrong but the feeling I get .