"We Need to Get Back To Some Happier Times in This County."

Sometimes people tell us exactly what is on their mind and at other times their words capture a much broader sentiment that situates them in a long and painful history.

The removal of Confederate monuments has slowed to a trickle since 2020-21. This is to be expected. One hundred and eleven Confederate monuments have been removed since the police murder of George Floyd in May 2020. That list will soon include St. Landry Parish, Louisiana.

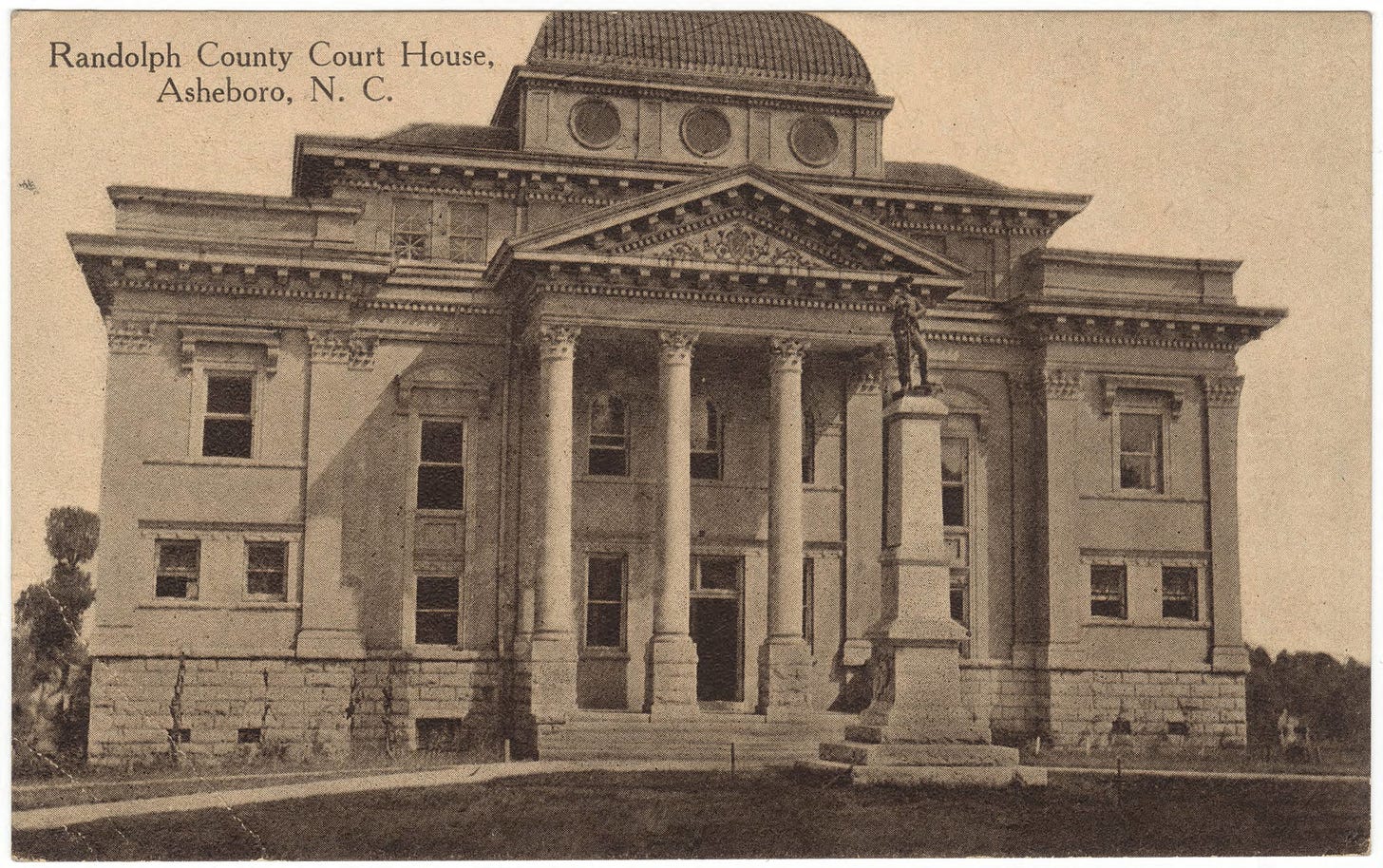

Other communities have decided to keep their monuments in their current locations for now. Randolph County, North Carolina is one of those communities, even though the NAACP campaigned hard for its removal. This particular Confederate monument has stood in front of the courthouse since its dedication in 1911.

I was struck by this comment from County Chairperson Darrell Frye, who was recently interviewed about the county commission’s vote to retain the monument:

We need to get back to some happier times in this county. I think we lived together pretty good for a number of years and then this thing started and it was like well other people is doing it so we need to do it.

Sometimes people tell us exactly what is on their mind and at other times their words capture a much broader sentiment that situates them in a long and painful history.

Mr. Frye’s words follow in a long line of white Americans mourning the loss of what they perceived to be peaceful race relations as a result of African Americans pushing for change. These words echoed during Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Era, and they can still be heard in 2022.

The irony is striking given the fact that these monuments helped to maintain those “happier times” by their very presence in places like courthouse squares. They served as a reminder of who was in charge and why.

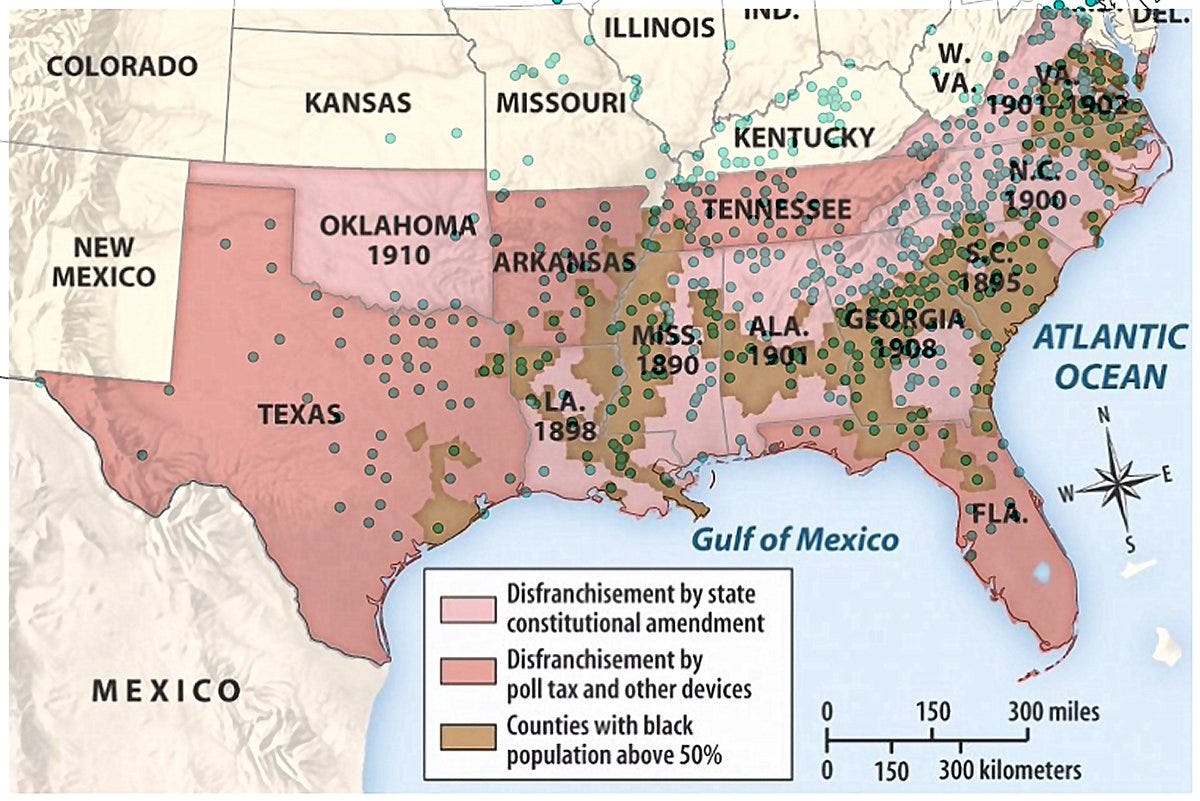

The flurry of monument dedications during the Jim Crow era was made possible as a result of legalized disfranchisement and the lynchings of thousands of African Americans. The memory of the war that these monuments enshrined offered a justification of Jim Crow’s racial hierarchy.

White political control made it possible to dedicate Confederate monuments like the one in Randolph County in 1911, as well as in places where over half the population was Black.

As I have stated numerous times, the problem isn’t that Confederate monuments no longer reflect the shared values and collective memory of the communities in which they are located. As you can see in the map above, the problem is that they never did.

What may have been perceived as “happier times” was the result of Black disfranchisement and their inability to take part in public discussions about who and what to commemorate in public spaces.

As historian Karen Cox demonstrates in her book Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice, African Americans have always understood the meaning and purpose of these monuments.

Thankfully, those “happier times” that Mr. Frye laments are long gone as a result of access to the polls and a national push to address the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction that these monuments helped to manipulate throughout much of the twentieth century.

Mr. Frye could certainly use a history lesson, but it isn’t a history lesson that will result in the removal of this monument. Nothing short of his removal from office (and others as well) will do that.

Thanks for reading. If you go ahead and subscribe to this newsletter you will be entered to win one of two copies of my book, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. Winners will be announced on March 18.

Heh. Happier times... The North Carolina Home Guard *Literally. Tortured.* Randolph County citizens during the Civil War. Remember that scene in Cold Mountain when the Home Guard killed one man and placed his wife's hands under a compressed fence rail? Yeah, that's taken exactly from what happened to Bill Owens and his wife (they lived on the Moore County side of the Randolph-Moore County line, but still.)

Also, in regard to "happier times," just two days ago I was talking with someone about a novel written by Sally Mae Dooley (of Richmond's Maymont) in what she regarded as Black dialect and from the point of view of an old emancipated Black man who lamented the new era of freedom. It's titled "Dem Good Ole Times."

Mr. Frye just should have put it that way.

In the 2010 census, Randolph County was 78.4% non-Hispanic white, and 6.6% Black. The African-American community will need a lot of allies to move “Mr.” Frye and his ilk out of county government. I hope they have them and are successful.