We Have a Responsibility to Understand Our Complex Past. We Have a Choice as to How to Commemorate It.

Confederate soldiers fought for a nation that was established to protect and expand the institution of slavery. They fought against the United States in armies that impressed tens of thousands of enslaved men to help achieve this goal.

John Lewis fought to bring this nation closer to its founding ideals of equality, justice, and a commitment to democracy. On battlefields throughout the South in the 1950s and 60s, in places like Selma, Alabama and Jackson, Mississippi, Lewis never surrendered to segregationists and their white terrorist allies. He was a soldier for freedom.

Today is the last day that you can take advantage of this special offer to subscribe to Civil War Memory at a discount. Become a paid member today and get 25% off for life. Just click the red button.

OFFER ENDS TONIGHT AT MIDNIGHT!

We have a responsibility to understand the history of the Confederacy and the men who fought for it as well as the civil rights era and the Black and white men and women who kept their ‘eyes on the prize.’

We have a choice as to which to honor and commemorate in our public spaces.

The people of Decatur County, Georgia, through their elected representatives, have made their choice.

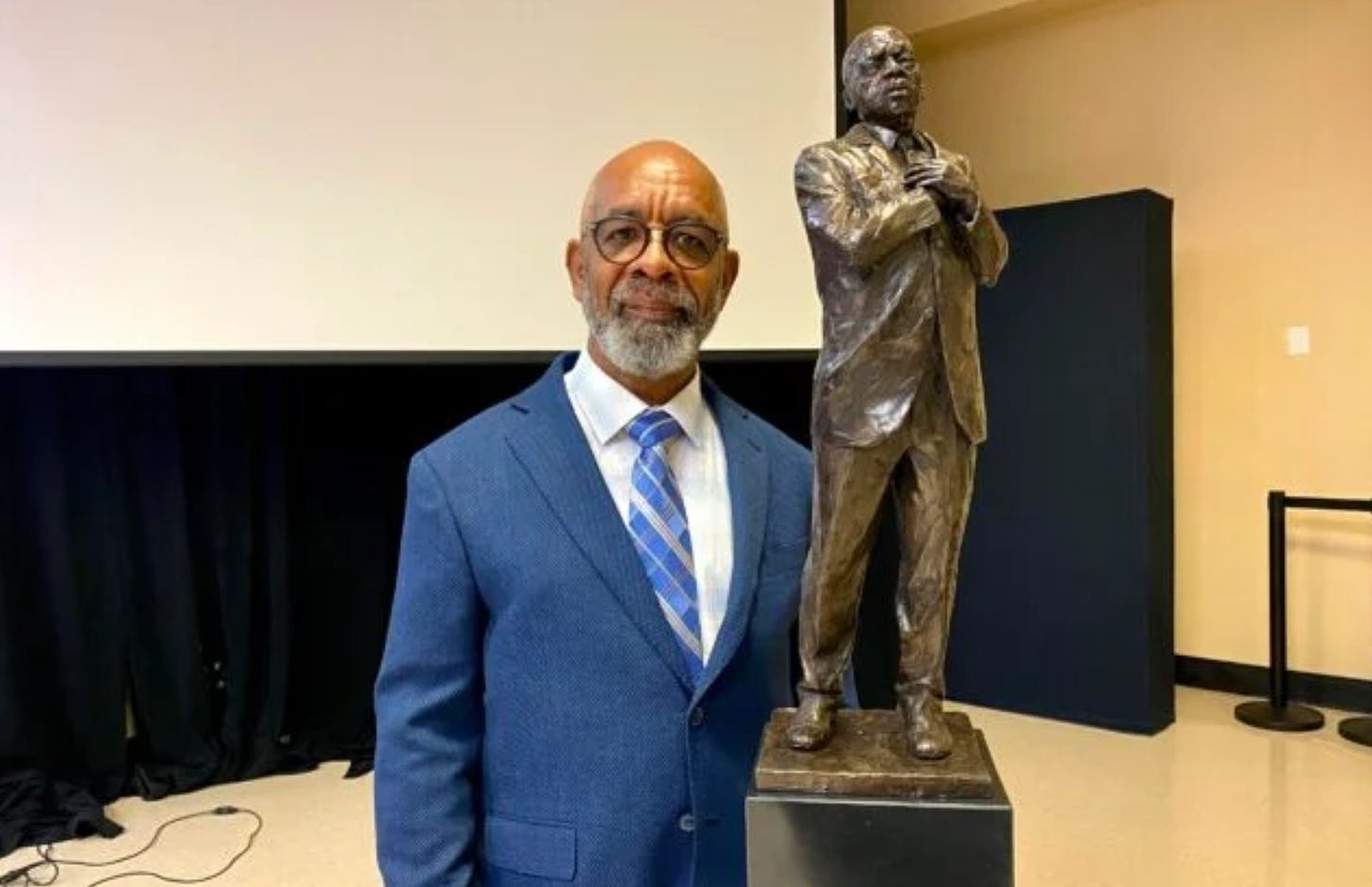

The John Lewis Commemorative Task Force recently selected Atlanta artist Basil Watson to create a statue of the late Rep. John Lewis that will be placed on the Decatur Square, where a Confederate monument once stood.

Rep. Hank Johnson, who represents Georgia’s 4th congressional district, believes that this is an ideal site for a new statue of Lewis.

I practiced law here. I was a magistrate court judge, a county commissioner. I just always felt like the city of Decatur was mine, but the truth of the matter is that every day of the 16 years that I have served in Congress, this area has been represented by Congressman John Lewis. This is his courthouse. This is his city. This is his location. It’s very fitting that as that Confederate monument was taken out, it’s a great area to put a memorial to a man who was not divisive and who was not about hate. He was about the opposite. He was about love, brotherhood, sisterhood, friendship. These were the ideals that John Lewis stood for.

The pace of Confederate monument removals has fallen off over the past year, but we are now beginning to see communities across the country move forward with how to utilize these empty spaces.

These are difficult questions as cities and towns work to find ways to represent and commemorate both their collective past and values. This never happened at the height of Confederate monument dedications at the turn of the twentieth century given the politics and violence of segregation.

There is a reason why you don’t find public spaces commemorating the end of slavery and Black United States soldiers in counties where African Americans were in the majority and it’s not because they weren’t interested in celebrating their history.

Roanoke, Virginia recently announced that a statue of Henrietta Lacks will soon be dedicated in a public plaza that was once named in honor of Robert E. Lee and where as statue of the Confederate general once stood.

Ms. Lacks, who was born in Roanoke and later moved to Baltimore with her husband during the 1940s, died from cervical cancer at 31 in 1951. She left behind five young children and an unrivaled medical legacy.

Just months before her death and without her knowledge, consent or compensation, doctors removed a sample of cells from a tumor in her cervix. The cells taken from Ms. Lacks behaved differently than other cancer cells, doubling in number within 24 hours and continuing to replicate.

The cell sample went to a researcher at Johns Hopkins University who was trying to find cells that would survive indefinitely so researchers could experiment on them. The cells derived from that sample have since reproduced and multiplied billions of times, contributing to nearly 75,000 studies.

The cell line named after Ms. Lacks, HeLa, has played a vital role in developing treatments for influenza, leukemia and Parkinson’s disease, as well as advancing chemotherapy, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization and more.

A temporary sculpture called Sentinel stood on the site of a former monument honoring Robert E. Lee in New Orleans before it was removed in August 2022. All four locations, where Confederate statues once stood in the city, have been repurposed at different times by local artists since 2017.

Though not on the same site, the city of Richmond dedicated The Emancipation and Freedom memorial just two weeks after it lowered Robert E. Lee from atop its pedestal on Monument Avenue.

We are going to see more stories like this in 2023 and beyond.

Following up on the point made above, it’s helpful to see this reimagining of public spaces as a process long overdue. Just as I believe communities should think carefully about the removal of monuments, they should also move deliberately in figuring out how best to move forward.

No decision is timeless.

Our understanding and memory of the past are always evolving. Our public spaces are for the living.

Have a safe and Happy New Year. See you in 2023.

That first sentence says it all. What percentage of Americans have never been taught this simple fact? What percentage of Americans know this and yet, continue to celebrate the confederacy? *smh*