Earlier this week The National Assessment of Educational Progress reported that 8th graders in the United States scored lower on their History and Civics assessment than they have since the Department of Education started testing for this in 1994.

No one seems to know why students did so poorly. Some are blaming the impact of the pandemic while others have highlighted the decreased time now spent in the study of history in many schools across the country. And, of course, Republicans and Democrats have their own self-serving explanations. On one side we are supposedly witnessing the results of “wokeness” and on the other restrictions imposed on teachers in Republican-controlled states.

I suspect that all of these factors have played some role to different degrees, but what I find interesting is that no one has pointed out that, from a historical perspective, there is little that is new here.

Students in the United States have always done poorly on standardized history exams. In 1917, 1,500 students in Texas from elementary school through college were tested and the results were dismal. They were able to identify 1492, but not 1776; confused Thomas Jeffeson with Jefferson Davis; and linked the Articles of Confederation with the Confederacy.

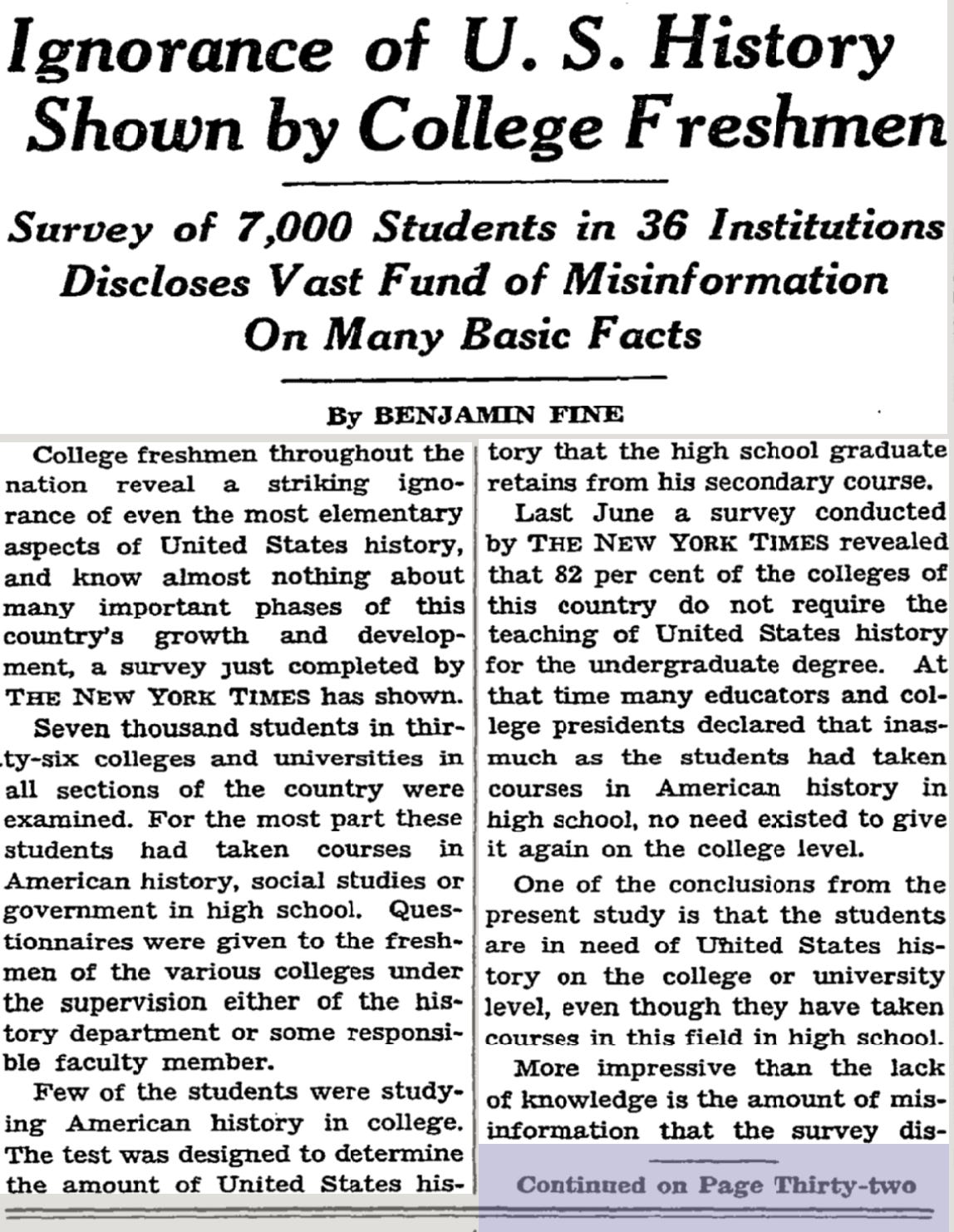

In the middle of World War II the New York Times published on its front page an article titled, “Ignorance of U.S. History Shown by College Freshman.” Just over five percent of students could identity the thirteen original colonies, while less than twenty-five percent could name two contributions from Thomas Jefferson. Abraham Lincoln both “emaciated the slaves” and was father of the Constitution.

I could go on and trace this pattern through the rest of the twentieth century, but the point I am trying to make is an obvious one. Every ten years a report is published highlighting how little our children know about American history and we throw up our hands thinking that this is the end of democracy as we know it.

According to Sam Wineburg:

A sober look at a century of history testing provides no evidence for the ‘gradual disintegration of cultural memory’ or a growing historical ignorance.’ The only thing growing is our amnesia of past ignorance. Test results over the last hundred years point to a peculiar American neurosis: each generation’s obsession with testing its young only to discover—and rediscover—their ‘shameful’ ignorance. The consistency of results across generations casts doubt on a presumed golden age of fact retention. Appeals to it are more the stuff of national lore and wistful nostalgia for a time that never was than claims that can be anchored in the documentary record. (p. 15).

It’s unclear to me as to why we place so much stock in these test scores. The parents and grandparents of the current generation of students didn’t perform any better on these tests.

There is no prima facie evidence that how well students understand American history, or for that matter any history, translates into a clear indicator of the overall health of the nation.

Given that the teaching of history has always been politicized, I suspect that the emotional responses of many are simply a reflection of their broader political world view. In other words, poor test scores—regardless of whether you are a Democrat or Republican—offers another opportunity to confirm to yourself and to others what is wrong with the other side.

None of this is to suggest that I don’t believe the teaching of history is not important, but rather that I stopped worrying about test scores a long time ago.

I hated history through most of my primary and secondary school years. It was only later that I was mature enough or in the right head space to appreciate the value of thinking historically. It would be interesting to know when in life and under what conditions people tend to turn to history for intellectual fulfillment.

For now, let’s put aside our concerns about test scores and political bickering and come together around something we can all embrace:

There is nothing more American than scoring poorly on a standardized history test. :-)

I am with you on raising issues about the standardized test scores. I am not sure how much they actually mean (pun intended) other than many people are not good test takers. I also think the same can be said for more general assessments of American education but that is a debate for another day.

But I also think, as I suspect you do, that test scores aside there are issues with the degree to which Americans, on both side of the political divide, understand and appreciate our history. Some of the problem is that in my state at least one can teach secondary level history (middle school, high school) only having taken what we used to call Western Civ I and II and US to and Since. All general education survey courses. This means often, I realize this is not always true, the people teaching history at the middle school/high school level have no more than a cursory knowledge of the subject. That is why things like the professional development projects you do are so important.

I have said this before, I think part of the task of the history teacher (especially in secondary school and at the general ed level in college) is to be a story teller. To tell her/his students stories that convey some sense of the soul of the nation. But in doing so you have to insure that those stories account for all the currents that come together at any point in time to create the contemporary culture, and that is of course the problem. It is almost impossible to do that. I am not advocating we throw up out hands and go have a bud Light. We have to keep trying.

I know I did not often get it right. As a military historian I told stories about the arrival of the Iron Brigade at Gettysburg or the ethnic make of up of Unitied States forces at the Battle of the Little High Horn, or the USS Nevada's run for the open sea at Pearl Harbor, or the role of the code talkers or the 442 Infantry. But there are lots of other stories, all worthy of being told, that I missed in making my decisions about what to focus on. Everyone does this, there is no way you can't and to some degree it short changes the students.

In my capacity as a public librarian, I help parents find books and resources for their kids, and I remember a specific instance a number of years ago helping a mom find historical fiction for her 3rd grader. This mom seemed irrationally upset about the fact that her kid had to read *air quotes* historical fiction, and struggled a little bit with how historical fiction was defined. The impression I was left with was that this mom was starting to recognize her 3rd grader was learning things she wasn't familiar with and it scared her.