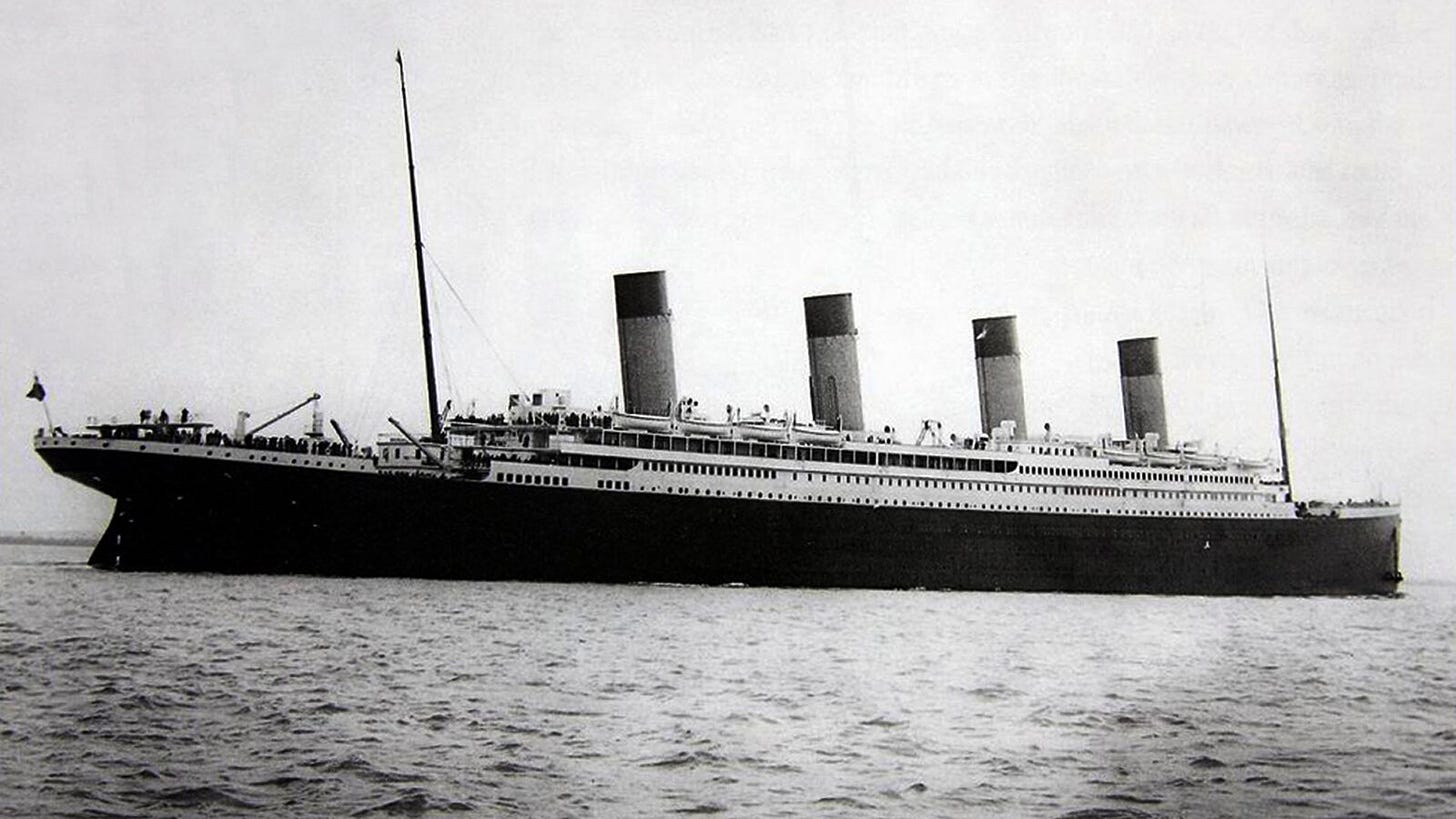

Like many of you I followed closely the story of the five passengers on the submersible Titan who lost their lives in a catastrophic implosion near the Titanic last week. I’ve been struggling to wrap my head around the motivation to risk one’s life for a glimpse of the doomed passenger ship that sank on its maiden voyage after hitting an iceberg on April 12, 1912, taking with it roughly 1,500 passengers.

I couldn’t help but ponder whether the passengers were serious about the history of the Titanic or just simply adventure seekers, who may or may not have seen James Cameron’s Academy Award-winning film 1997 film and who could pay the costly ticket fee.

Only one passenger, Paul-Henri Nargeolet (aka “Mr. Titanic”) seemed to have the credentials to be considered a serious student of the history of the ship and the wreck. The other four, I believed, were simply reckless, irresponsible, who thought only of themselves.

It was easy for me to take this perspective given the work that I do leading tours to historic sites. It takes extensive preparation and a certain creativity to structure a tour that is both historically accurate, entertaining, and meaningful.

The 2-hour trip to Titanic in a cramped tube and roughly 2-hours exploring the wreck would offer none of this beyond perhaps an occasional comment from Mr. Nargeolet. I could envision little more than a strained attempt to peer through a small viewing window waiting for that iconic view of the ship’s bow.

What I did not consider was simply the power of the story. The costs and risks of such a deep dive are a reminder of just how far we will go to chase down stories. Ultimately, the question of whether the passengers were serious students of the history of the Titanic is irrelevant.

The question itself obscures the deep need that each of us has to connect our own lives to a history much larger than our own lives. Some of us find it in literature. Many of you reading this blog find it in history and on your visits to historic sites.

In the days and weeks following the battle of Gettysburg civilians flocked to the battlefield to catch a glimpse and to feel a part of an unfolding drama that many already believed would have historic significance. We continue to return 160 years later chasing old and new stories and yearning to feel a part of the landscape and broader story.

These stories, as the philosopher Daniel Dennett argues, are fundamental to our self-identity:

We, in contrast, are almost constantly engaged in presenting ourselves to others, and to ourselves, and hence representing ourselves—in language and gesture, external and internal. The most obvious difference in our environment that would explain this difference in our behavior is the behavior itself. Our human environment contains not just food and shelter, enemies to fight or flee and conspecifics with whom to mate, but words, words, words. These words are potent elements of our environment that we readily incorporate, ingesting and extruding them, weaving them like spiderwebs into self-protective strings of narrative. Our fundamental tactic of self-protection, self-control, and self-definition is not building dams or spinning webs, but telling stories—and more particularly concocting and controlling the story we tell others—and ourselves—about who we are.

We give little thought to the fact that we engage in storytelling. These stories weave us as much as we may believe that we are their authors.

I am not trying to be mystical, but simply want to point out that we may be hard wired to seek out and tell stories that give meaning and structure to our lives in the same way that spiders spin webs.

Two weeks ago I awoke at 4AM to drive 7 hours to Gettysburg. The place and its history continues to pull me in ways that I couldn’t even begin to explain. There is a transformation that takes place with each passing mile. My sense of awareness of history and my place in it becomes much more acute as I drive the last few miles along the Old Harrisburg Road.

It’s about the stories of the past that I have the opportunity to revisit as well as the promise of new stories that continues to spark my fascination and keeps me coming back.

Now that I think about it, trying to understand the pull of the Titanic for those people who have found meaning in its story should have been the easiest thing for me to understand.

Kevin, I think this is a great post. I think there is a need for lots of reasons to connect to something greater than ourselves. I think it partly explains the myriad of NPS historic sites and their visitor numbers.

I have an experience similar to yours with several sites I regularly visit. Several years ago while walking the American line at Saratoga I stopped at the site of an American battery and surveyed the far tree line with a monocular. As I was standing there it occurred to me I probably wasn’t the first American officer to stand on or near that spot and ponder where the other guys would come out tree line and how they would try to cross the open ground to my front. Nothing mystical going on but connections to people who had gone before me? Yes. I think that’s why so many Americans of all political persuasions visit these places. And, I think the contribution of people like you with the battlefield tours, good battlefield tours, is to make the experience more meaningful.

I can't comment with any authority on the Oceangate Titan, except to point out that I'm too claustrophobic to ever try anything like that myself, that one of the five apparently was dragged there against his will, and that the reveling I see elsewhere on the net about his death and the death of his billionaire father with words and memes says something very disturbing if perhaps too understandable and familiar about our society. And that we ought to just as interested in that fishing boat filled with migrants that sank off Greece.

But I get the lure of stories. I come from a long line of storytellers. But why these particular stories? Not all possible stories are equal. Why Titanic and not any number of alternatives? Why was Gettysburg crawling with tourists and buses when we were there, but Antietam was all but empty?

I don't think we can discount the hegemonic role of western popular culture, which teaches us that some events--"words" to paraphrase Dennett--are more important than others. Titanic is a good case in point. I remember watching "A Night to Remember" as a kid, and I think I had read the book before I went to high school. But there was a lot more than that. How many times did the Titanic disaster pop up as a punchline, as an analogy, as a reference on this game show or that sitcom? As an RV on "Trapper John MD?" As a bit of language? As something we needed to know about in order to communicate with our peers? As something in the air? We were *taught* that it was important, in the same way that the culture simultaneously *taught* me (a kid growing up during the later years of the Civil War Centennial) that the Civil War was of central and vital importance, in a way that say World War I supposedly was not. That war was everywhere in 1960s Virginia--in school, school trips, roadside markers, flags, battlefields, a "Forget Hell" sign in my dentist's office, the toy caps and guns in the gift shop at the zoo, Lincoln's Birthday sheet sales, the penny, in serious films, on the news, in westerns, and at the center of a particularly insightful arc on "the Beverly Hillbillies" (really). And Gettysburg supposedly was the most important part of that vital war. All those were our "spider webs." How can we not feel chills on that field? It's our Troy.

One summer I worked construction, with one other college kid and a group of ex-cons. Best co-workers I ever had actually. They could intelligently talk about the Civil War too. Probably they could discuss the Titanic.

Perhaps we are "hard-wired" to gravitate toward such stories, I'm not equipped to debate that, but in the nature vs. nurture debate we've also been taught in innumerable ways large and small that stories matter, and that these are the stories that really matter. I absolutely get why those people (four of them anyway) wanted to dive on the wreck. I went to the same school, for good or ill. It shapes and constrains.

Thanks for letting me ramble.