No aspect of the Confederacy can be understood without acknowledging the importance it placed on the institution of slavery. Confederate civilians were reminded that their nation was defending a ‘peculiar institution’ at every turn. Enslaved men worked manufacturing war materiel in places like Richmond and Atlanta and they marched off with their masters to war as body servants or camp slaves. On the home front their forced labor made it possible for the nation to field armies with the goal of maintaining their enslavement.

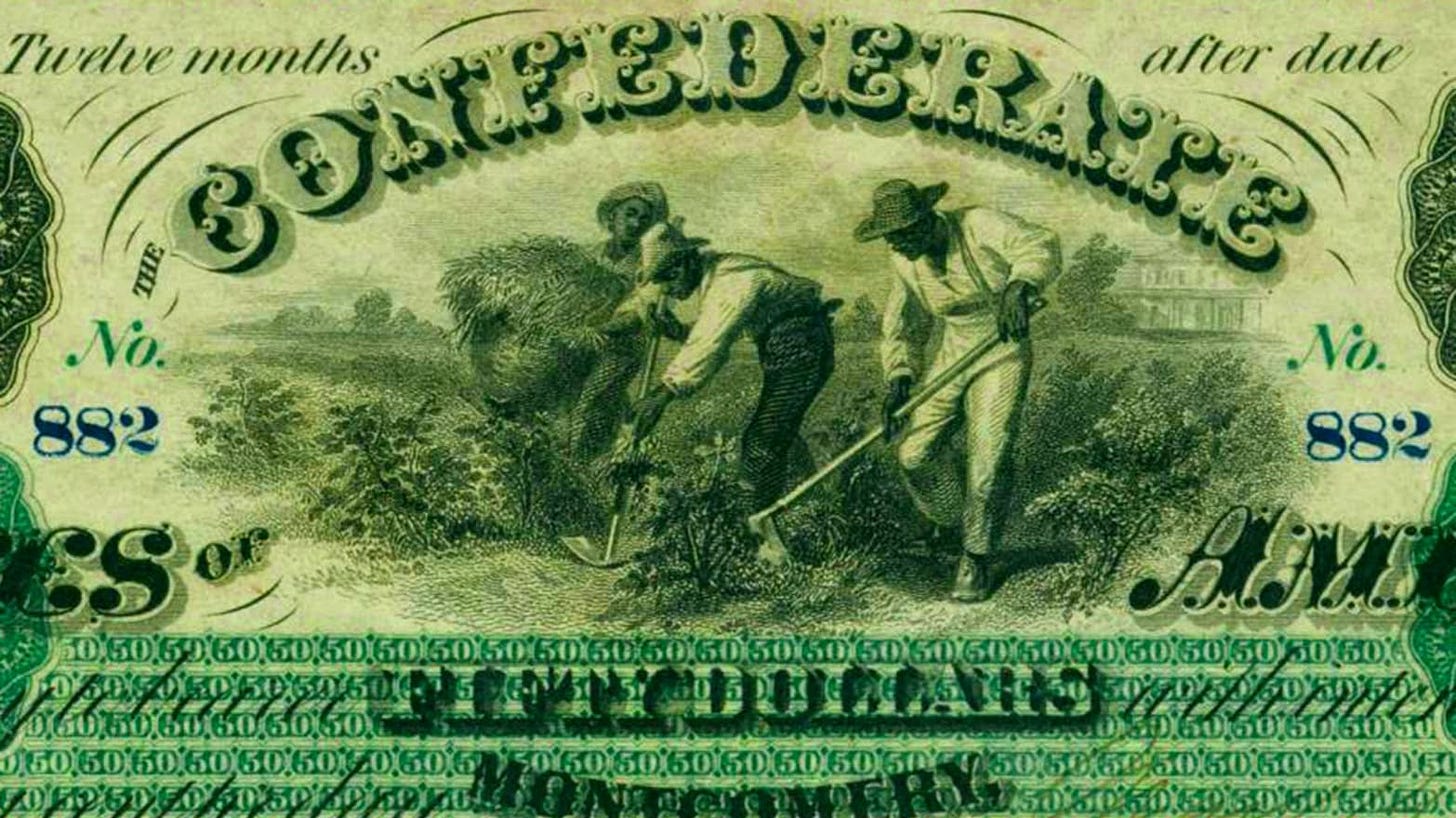

Confederates were also reminded of the “cornerstone” of their republic in the very money that they used throughout the war.

African Americans were depicted in a wide range of scenes on Confederate currency during the first year of the war. Their presence reveals how leaders of the new nation hoped to be viewed by foreign countries but, more importantly, these banknotes or Treasury notes highlight the importance that Confederate leaders placed on the preservation of slavery and white supremacy to their new nation. In early 1861 Vice President Alexander Stephens unapologetically argued that the preservation of slavery and white supremacy were the “cornerstones” of their nation. The inclusion of representations of slavery on Confederate currency suggest that, far from trying to conceal it, this new nation celebrated it as a mark of their “American Exceptionalism.”

Images of slaves on currency in the 1860s were not new. Individual Southern states included scenes of enslaved blacks on their currency beginning in the 1820s, which helped to fuel the expansion of the Cotton South and its place in a vibrant Atlantic economy that extended to European banks and manufacturing centers.

The first Confederate banknotes introduced images that became commonplace moving forward. Political icons such as presidents George Washington and Andrew Jackson attest to the Confederacy’s embrace of iconic national leaders and a need to secure its legitimacy. The inclusion of South Carolina Sen. John C. Calhoun reflects his role as the intellectual father and defender of the slaveholding South. These men were featured alongside popular symbols of liberty and freedom as well as symbols of the goddess of peace (Minerva) and the goddess of agriculture (Ceres). Vignettes of slaves round out numerous individual bills and point to what was distinct about Southern society. Their placement among these other representations provided reassurance that slavery was protected both by law and by tradition.

The $50 bill issued in Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1861, for example, features slaves hoeing cotton. Like other vignettes it is a peaceful pastoral scene that depicts slaves diligently working without any oversight and in full view of the plantation mansion. These scenes provided a stark contrast to how many white Southerners perceived their Northern neighbors, who had embraced a morality associated with industry and free labor. Issued a few months later, the $10 bill once again depicts slaves in the field, this time during the harvest season. Both bills introduce slaves that are well dressed and working without any threats of physical violence, which by the beginning of the war had defined many Northern accounts of the South’s “peculiar institution.”

A slave loading cotton bales onto a cart and a sailor leaning against an anchor on the $100 bill—also authorized in 1861—evokes the hopes of a peaceful end to the war. At the beginning of the war, Confederate officials prevented the sale of cotton to England in hopes that economic necessity would force it to push for a peaceful settlement. This never happened and within a short period of time the U.S. Navy bottled up Confederate shipping with a blockade, leaving stockpiles of cotton bales rotting on wharves.

For a nation now at war, scenes of working slaves provided reassurance that victory was possible. They depicted a unified nation with white men serving in the army and loyal slaves on the home front doing the necessary work to ensure a regular supply of food. Whatever fears the men harbored as they left home for the army, these images provided some reassurance that their loved ones were in safe hands with their slaves. Internal problems surfaced immediately, but Confederate currency provided some reassurance that the nation remained unified across both class and racial boundaries.

Images of slaves disappear from Confederate currency issued after 1862 in favor of a new nationalism that highlighted the nation’s leaders, martial symbols, and scenes of war. Bank notes featured Confederate leaders such as Davis and Stephens as well as the martyred “Stonewall” Jackson, the only general featured on Confederate currency. The disappearance of slaves from Confederate currency can be attributed to a growing belief among the poor that the wealthy slaveholding class was exploiting them to defend a system that they had been excluded from. This was reinforced in October 1862 when the Confederate government passed the Twenty Negro Law, which exempted one white man from the slaveholding class for every 20 slaves as a means to prevent violence on the home front.

In contrast, state banks continued to issue currency that included scenes of happy, loyal slaves working cotton fields and engaging in other agricultural tasks through to the end of the war. This represents a continuation of the antebellum emphasis on the virtues of the slave system and even continued for a time after the war ended. Lingering notes that circulated briefly during the postwar period served to remind ex-Confederates of their Lost Cause and the freedom of 4 million people.

Fantastic article! Good examples of material culture.

I spent some time with state banknotes from 1860 last week and there are as many stock images of railroads as there are of enslaved people. That's not to diminish the power and meaning of enslaved workers, but rather, in context, helps us see their own self-conception as inclined toward the modern technologies of global capitalism--and slavery is firmly a part of that just as much as international money markets, railroads, and undersea telegraphs. (As opposed to how we used to think of them--as quaint, locally inclined, agriculturalists uninterested in modernity.)

Anyhow, I did not know that CS notes began dropping slavery images toward the end. What evidence do we have that they did so as not to antagonize non-slaveholders. (I'd believe it, but I'm wondering how we know.)