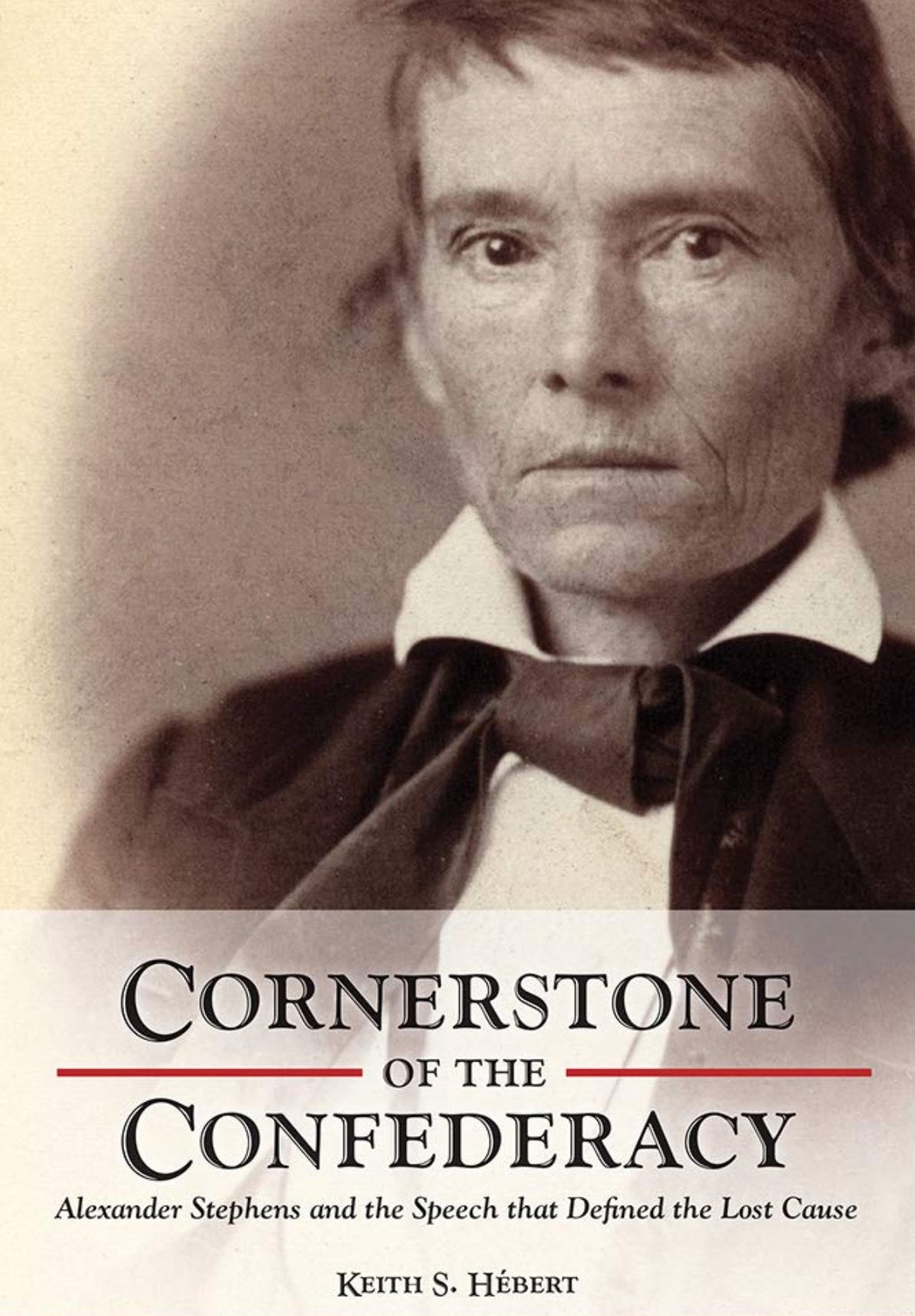

Just sent off a review of Keith S. Hebert’s new book, Cornerstone of the Confederacy: Alexander Stephens and the Speech that Defined the Lost Cause to the Georgia Historical Quarterly. I highly recommend it.

The Cornerstone Speech is a touchstone of Civil War memory. Many of you are no doubt familiar with its key passage:

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

Stephens delivered this speech on March 21, 1861, a little over a month after the formation of the Confederate States of America and his election as its first and only vice president.

Memory has a way of setting certain moments in stone and that is certainly the case here even though Stephens tried desperately to distance himself from the speech during the postwar period and the rise of the Lost Cause narrative of the war.

According to Hebert, the Cornerstone Speech “represented the eroding middle ground between secessionists and Unionists that Stephens once occupied.” (p. 49)

Indeed, just three months earlier Stepehens delivered a speech to the Georgia state legislature against immediate secession. “In my judgment,” argued Stephens, “the election of no man, constitutionally chosen to that high office, is sufficient cause for any State to separate from the Union. [The South] ought to stand by still and aid in maintaining the Constitution of the country.” (p. 27)

For Stephens, the election of the nation’s first Republican president did not represent an immediate threat to the institution of slavery and white supremacy as it did for the rest of the Deep South states. His views echo those of elected leaders in the Upper and Border South who embraced a wait-and-see approach to the new administration.

Stephens acknowledged that Lincoln had been fairly elected and that any attempt to secede would be a violation of the will of the people. Lincoln did not hold absolute power and there were divisions even within the Republican Party. “If the South left Congress,” counseled Stephens, “no one would be left to check the power of the Republican Party.

His larger concern, however, was a conviction that even with the election of Lincoln and Republican control, slavery was still safer in the Union than outside of it.

Stephens also warned his fellow legislators of the dangers of war with the United States. A union of slaveholding states would fight under major disadvantages owing to its smaller population and lack of industry and would cost “tens of thousands of your sons and brothers slain in battle.”

In closing, Stephens reminded his audience that the slaveholding South benefited from its place in the Union:

For you to attempt to overthrow such a government as this…in which we have gained our wealth, our standing as a nation, our domestic safety while the elements of peril are aourund us, is the height of madness, folly, and wickedness, to which I can neither lend my sanction nor my vote. (pp. 27-28)

According to Hebert, this is the speech that Stephens wanted to be rememered for.

It’s a reminder of the importance of contingency in history. There is a lesson in being reminded that the words so closely associated with the Confederacy’s commitment to slavery and white supremacy as its very “cornerstone” came from someone who was initially steadfast against secession and the establishement of a new nation.

Does the book go into how/why Stephens changed his thinking?

Fascinating. I had not ever heard of Stephen's earlier position as a somewhat more moderate voice thanks for this insight.