Reminder: I will be sending out a zoom link to the email addresses of all paid subscribers for Sunday evening’s discussion about the movie GETTYSBURG, which will take place at 7PM EST. Still time to upgrade if you would like to join us.

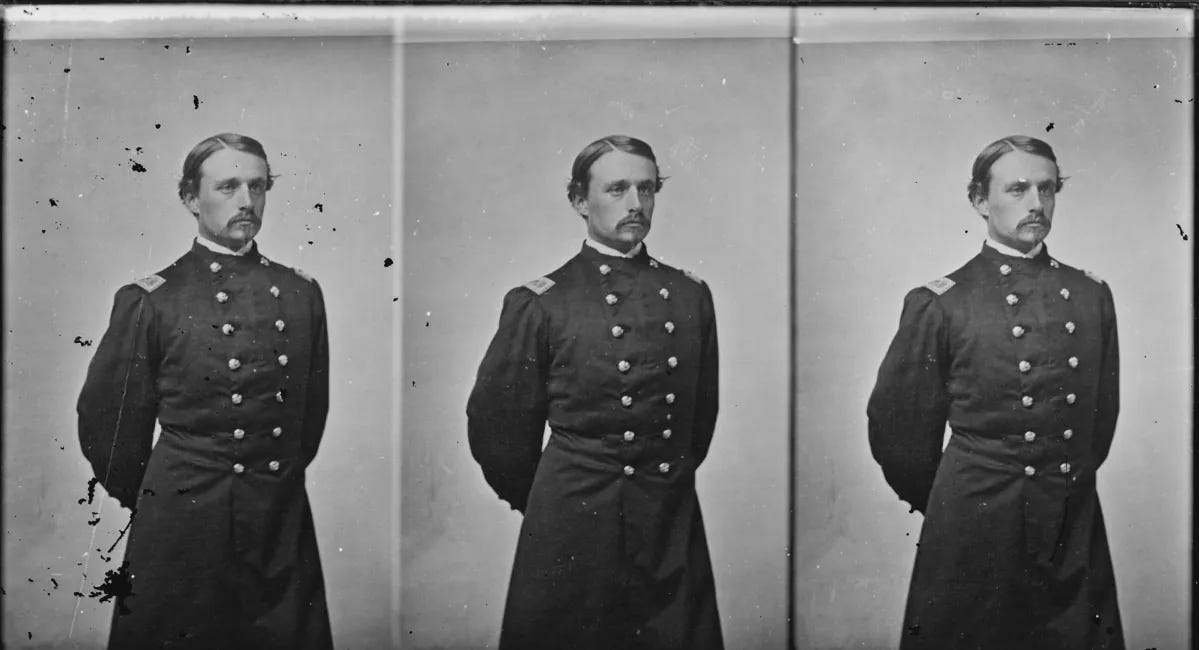

Last week I shared a bit of writing from my current book project about Robert Gould Shaw, specifically about his views of the freedpeople along the sea coast islands of South Carolina and Georgia. Our popular perception of Shaw, especially given our emphasis on race and emancipation, leaves little room for views that today strike us at best paternalistic and at worst racist.

A reader left the following comment:

I wish the paternalism had been confined to Shaw, but it arises again and again in accounts of white people working to help the freedpeople. Seems to show that good motives and even personal experience do not overcome embedded prejudices/world views.

It certainly does and it can be somewhat draining the more you come across it, especially from people who we assume should have known better, but of course, that is part of the challenge of studying history. We must always remember that they did not occupy our world.

In Shaw’s case, I am struck by how little he appeared to evolve in his attitude towards the African Americans he came across during the roughly eight weeks he was stationed in the low country before his death at Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863.

In last week’s post I offered a few examples of his interactions with the few formerly enslaved people still on St. Simon’s Island during the brief period that Shaw and the Fifty-fourth was stationed there between June 10 and the end of the month.

Today I am going to share a bit more about Shaw’s experience interacting with African Americans, this time on St. Helena Island, where the regiment was stationed from June 25 until July 8.

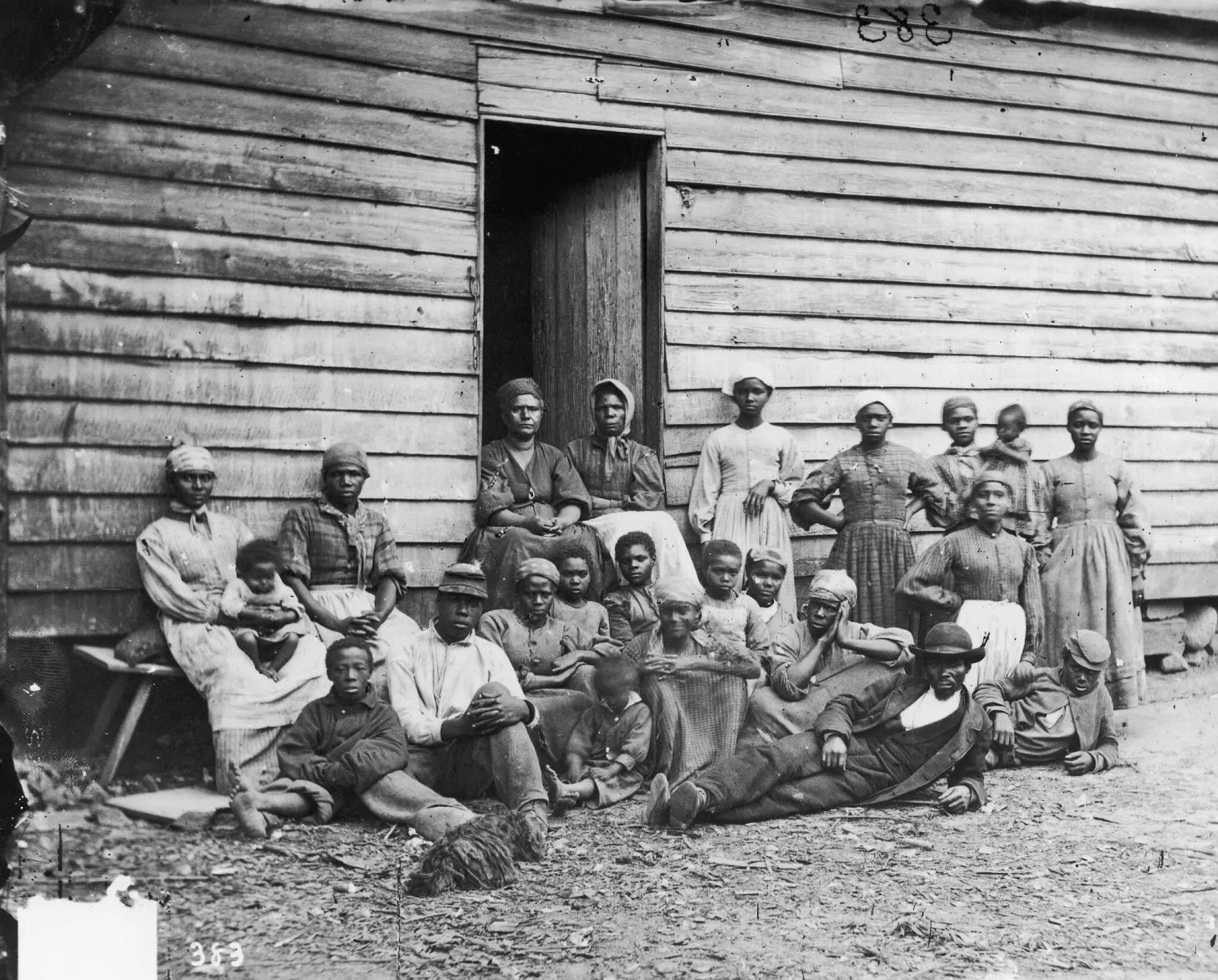

In addition to the movement of troops, St. Helena buzzed with the labor of thousands of freedmen now working for wages on the many plantations that dotted the island. At the Penn Center, just a few miles from the encampment of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts, children attended school in the Brick Church, where they learned spelling, writing, grammar, diction, history, geography, arithmetic, and music.

Shaw acknowledged the revolutionary impact of the Port Royal experiment, writing enthusiastically to his family about taking part in a “colored abolitionist meeting” at a plantation. “There were collected all the free slaves on the island, listening to the most ultra abolition speeches that could be made, while two years ago their masters were still here, the lords of the soil and of them. Now they all own something themselves, go to school and to church and work for wages!” “Such things,” he observed, “oblige a man to believe that God is not very far off.”

Shaw’s positive assessment of the radical changes he had witnessed on St. Helena, however, stand in sharp contrast to his personal interactions with the island’s freedpeople. In these moments, Shaw continued to embrace the same tired and demeaning characterizations of African Americans that he had shared with his family going back to his first foray into Virginia in July 1861. “Whatever the condition of the slaves may be, it does not degrade them, as a bad life does most people,” he observed “for their faces are generally good.” Shaw attributed this “to their utter ignorance, and innocence of evil.”

Shaw interacted “with a good many” of the freedpeople around St. Helena Island, but his conversations only served to reinforce his paternalistic and racist sentiments. “Whatever their habits of life may be, they certainly are not bad or vicious;” he observed “they are perfectly childlike it seems to me, and are no more responsible for their actions than so many puppies.”

Shaw was not unique in his views about the formerly enslaved. In fact, they were quite common throughout the nation, including among the reformers working in and around Port Royal, who were committed to uplifting the freedpeople. Some, however, eventually returned to their families having abandoned their work to help educate and train former slaves for citizenship. One person described such reformers as having succumbed to the “Plantation Bitters.”

Shaw never described the men in the Fifty-fourth in such language, which suggests that he distinguished between the moral character of free Blacks raised in the North and enslaved or formerly enslaved African Americans in the South. To whatever extent Shaw acknowledged that his men were fighting for a more prominent place in a reconstructed nation, it did not extend to the men and women he met on St. Helena Island. In fact, it is just as likely that Shaw shared these doubts and failed to see these people as future citizens.

Certainly not much had changed between St. Simon’s and St. Helena Island in terms of Shaw’s beliefs about race, but let me suggest that perhaps we are placing too much emphasis on his state of mind.

What I am learning to appreciate more and more as I study Shaw is the place he occupied in a broad coalition that made it possible to win the war and abolish slavery. This broad coalition included individuals who often had little in common and disagreed over fundamental questions having to do with the conduct of the war.

Consider, for example, colonels Thomas Wentworth Higginson and James Montgomery, who commanded the First and Second South Carolina “Colored” Regiments respectively. Higginson and Montgomery, along with Robert Gould Shaw, all commanded Black soldiers, but they differed with one another in a number of ways.

[I want to thank Todd Mildfelt and David D. Schafer for sending me a copy of their new biography of Montgomery, which was just published by the University of Oklahoma Press. I am thrilled that I will be able to make use of it in my Shaw biography.]

Both Shaw and Higginson expressed their disagreement with Montgomery’s mode of warfare and command style, most notably following the Darien expedition. Shaw and Higginson disagreed as to whether Black soldiers were capable of organized fighting as opposed to their involvement in smaller raids into the interior of South Carolina and Georgia.

All three men believed that slavery was immoral, but they differed significantly in terms of how they perceived African Americans. Their paternalism and outright racism was expressed in very different ways. Montgomery had spent the last ten years of his life fighting against slavery, beginning on the Kansas frontier in the mid-1850s, but he harbored deeply racist views.

When the 54th Massachusetts and other Black regiments refused the federal government’s decision to pay them less than white soldiers, Montgomery offered the following observation:

You are a race of slaves. A few years ago your fathers worshipped snakes and crocodiles in Africa. Your features partake of a beastly character. Your religious exercises in this camp is a mixture of barbarism and Christianity.

Despite their differences, these three men were part of a broader coalition working toward the abolition of slavery.

Shaw may not have thought much at all about the future of African Americans in a reunited nation, but he was allied with men in his regiment who gave this question a great deal of thought and who were willing to lay down their lives for the chance to become citizens and push the nation forward.

Though Shaw and his parents disagreed over fundamental questions concerning the war, including emancipation, they ended up as allies in the fight to end slavery.

The war created the space and opportunity for individuals from sometimes wildly different backgrounds and with different beliefs to find common ground around complicated issues such as slavery and emancipation These opportunities had less to do with what people believed and more to do with a calculation of whether forming a coalition would advance their interests.

Shaw’s significance, in my mind, and the reason his story is worth telling is because it provides us with a fascinating case study of how revolutionary moments, such as a civil war, can place someone in a position—alongside perfect strangers in every sense of the word—where they are able to help bring about significant change.

I tried several drafts of a comment but deleted them all. They sounded preachy. I think the best you may be able to say is Robert Gould Shaw was a complex product of his times. His actions (leading a regiment of Black United States soldiers at a time when this was considered highly unusual) do not seem consistent with some of the things he said and appeared to think. He was a complex person of contradictions caught up in a time of great change to his culture. Making sense is I suppose part of the historians struggle (still sounds preachy).

wow I want that book, but how about a look at what the WASP officers said or thought about their Irish troops and German Troops also. I bet there was a fair amount of bigotry there too.