On April 2, 1865 the Confederate government and military abandoned their capital city. The looting of stores and a general lawlessness prevailed downtown. As the last Confederate soldiers left the city they set fire to warehouses and other buildings to prevent the confiscation of war materiel and other valuable supplies by the United States army. The fire department was unable to prevent it from spreading.

The fall or surrender of Richmond has traditionally been viewed through a Lost Cause lens. After the war white Richmonders and white Southerners generally viewed it as the beginning of the end of the Confederacy. Six days later Confederate general Robert E. Lee would surrender the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. The events of early April 1865 reinforced the belief that even though the Confederacy had succumbed to the overwhelming resources of “Yankee” invaders, their military leaders remained untarnished Christian warriors and their cause remained righteous.

But this story has long overshadowed what actually took place in Richmond on April 3, 1865. In 1860 the population of Richmond was roughly 38,000, including 11,739 enslaved men, women, and children. Roughly 2,600 free Blacks also resided within the city’s limits. The population of Richmond soared during the war, including the number of enslaved people. [Finally, let’s not forget the white Unionists who also lived in the city.]

When we consider these numbers the arrival of the United States army in early April transforms the surrender of the city into its liberation.

White Richmonders acknowledged it as such in their letters and diaries.

Henri Garidel spent part of the war in Richmond after being expelled from New Orleans in 1863. He worked as a clerk in the Confederate Bureau of Ordnance. Garidel was unable to leave on the last train that left early on April 3. As a result…

I became a witness to the greatest disaster I had ever seen. First, our own men, during the night, had broken open the privates stores on Main Street and had looted them all, the most awful thing in the world. Then the government employees, having opened up their supply depts for the public to pillage, put fire to them. There was as strong wind, so the whole commercial sector of the city was reduced to ashes from Ninth to Fifteenth Street[.]

I finally went home and shut myself in my room, desolate, and from there I witnessed the entrance of the Yankees into Richmond. The Negro troops were the first to come in after the cavalry. It made your heart bleed to see with what joy the army was received by the population, particularly the Negroes. Their hurrahs filled the air, and there were Yankee flags flying on all sides.

The celebration continued the following day.

I got up at seven, more distraught than ever… The whites are very polite. They have posted guards at every block to maintain order. The Negroes of Richmond are in a state of great jubiliation. They have almost all come out into the streets.

Later that day a 33-cannon salute signaled the arrival of President Lincoln:

We didn’t know what it meant, but a moment afterwards we heard a lot of cheering, and we saw passing by right in front of the house the celebrated Lincoln in a carriage drawn by four horses, accompanied by his staff and a cavalry company and followed by the entire Negro population of Richmond who were shouting hurrahs. Their cheers were filling the air. I have never seen such an outpouring. I went out to go to the square, thinking Lincoln would go there, to see what would happen next, but I ran into so many Negroes and Negresses there that I couldn’t stand it. I went home, heartbroken.

Garidel no doubt spoke for most white Richmonders, but these stories never found a place in the public memory of the city after the war. After all, formerly enslaved people celebrating their freedom in the streets didn’t fit into the Lost Cause’s “loyal slave” narrative.

For Black Richmonders, however, the stories of the city’s liberation remained central to their collective memory throughout the postwar period.

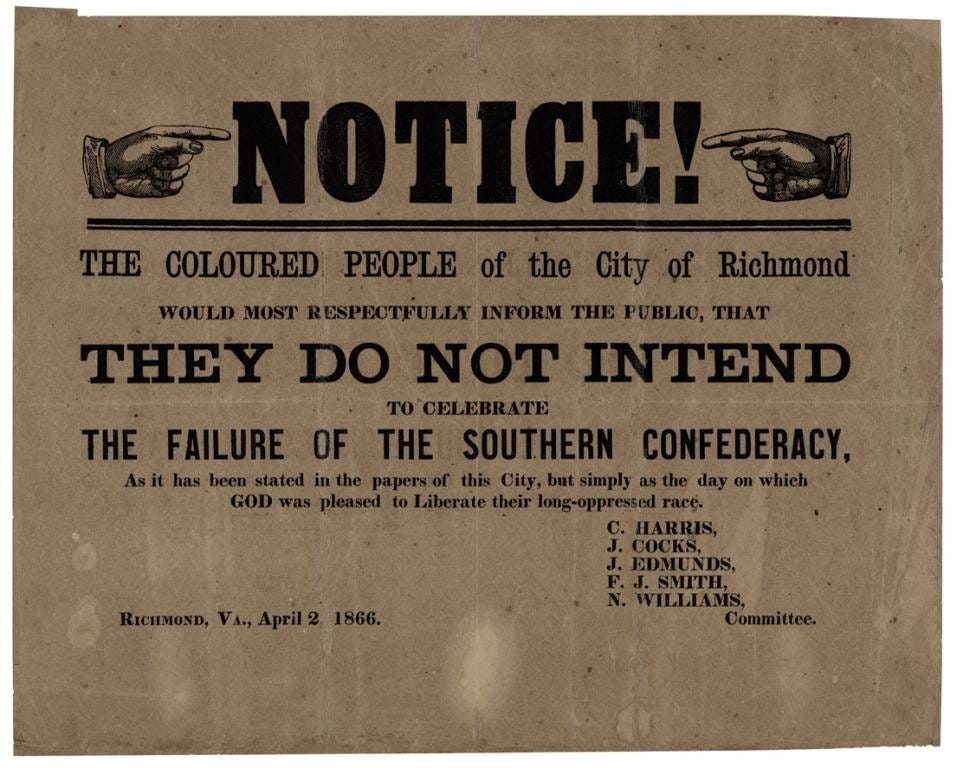

Just one year later, Black Richmonders celebrated the fall of Richmond and their liberation with a a parade in the streets. Black leaders went out of their way to reassure their white neighbors that they were not celebrating Confederate defeat, though this likely reassured very few.

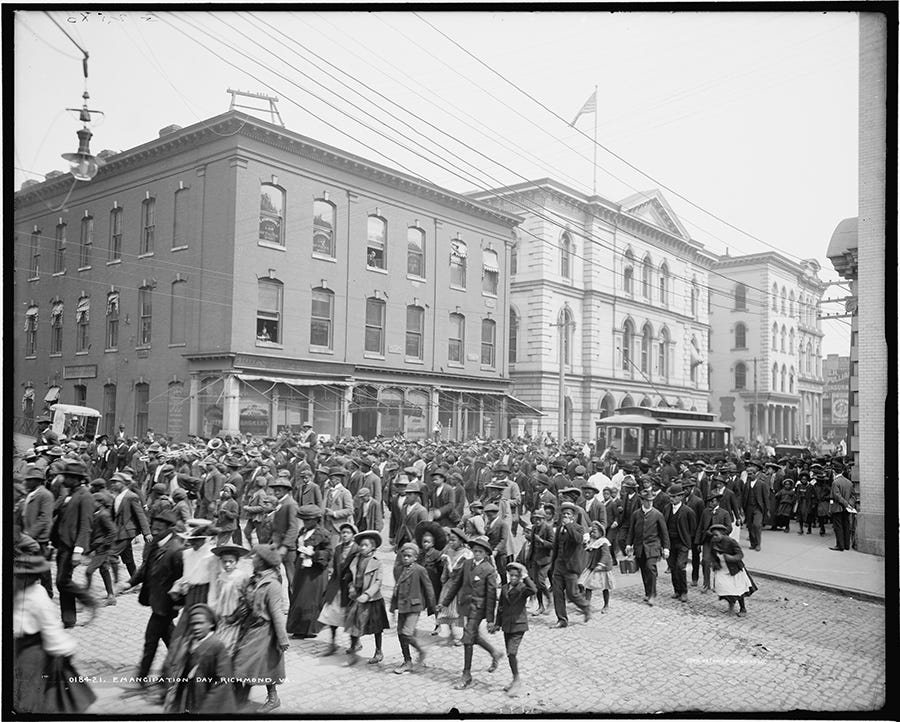

These celebrations continued into the twentieth century during the height of the Jim Crow era. By then a generation born into slavery and freed in 1865, their children and grandchildren marched together down Broad Street in Richmond to celebrate freedom.

Unfortunately, legalized segregation and racial terror ensured that an “emancipationist” memory of these events would never be recognized by the city of Richmond. Instead, Richmond’s monument landscape was soon dominated by Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and a host of other monuments that celebrated the Confederate soldier. These monuments reinforced the Lost Cause as the official public memory of the war as well as its segregated neighborhoods.

With everything that has happened over the past few years, it’s difficult to imagine that this was still the dominant memory of the war in Richmond at the turn of the twentiety century.

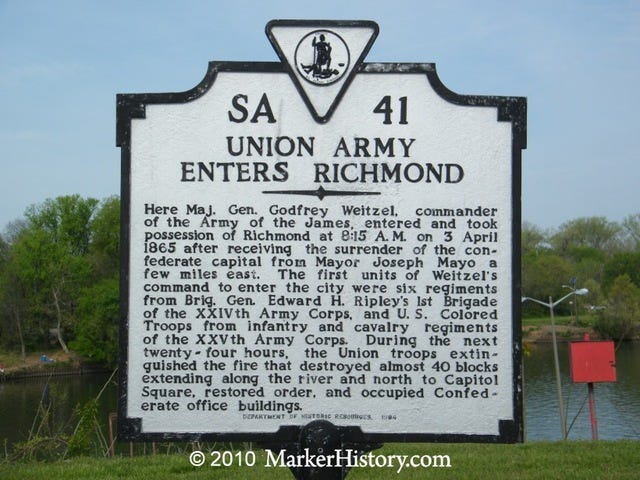

Much has changed in recent decades. In 1994 a new historical marker was dedicated in Richmond that acknowledged the role and presence of Black soldiers in the occupation of the city.

The filming of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” (released in 2012) took place in Richmond—a film that told the story of the passage of the 13th Amendment in January 1865. In 2010 Virginia stopped recognizing April as Confederate History Month.

The most significant changes would have to wait for the 150th anniversary or sesquicentennial commemoration of the Civil War. Virginia and Richmond led the nation in framing public events around a more nuanced narrative that downplayed the Lost Cause and highlighted emancipation and the service of Black soldiers.

Historian Edward L. Ayers, who helped organize numerous programs during the 150th, described the goals of events commemorating Richmond’s surrender in April 2015:

We’re trying to tell three major stories at once. The evacuation of the Confederate government, which hastens the end of the Confederacy, the ending of slavery here and the arrival of the U.S. Army. World history turned around Richmond that day, thus it seems only fitting that we acknowledge this by telling about these events from many viewpoints. If we as a city and region don’t do it, then, somebody else will.

You were just as likely to see Confederate reenactors as you were Black and white Union soldiers (along with Lincoln) walking the city’s streets in early April 2015.

But even the noticeable shift in public memory during the sesquicentennial could not have prepared anyone for the removal of much of the city’s Confederate monument landscape, beginning in the summer of 2020 and following the police murder of George Floyd.

The removal of Confederate monuments has been accompanied in recent years by the dedication of new monuments that reflect the shared history and values of a much larger percentage of the Richmond community. Museums and other institutions now tell the story of Richmond’s liberation in April 1865 and the broader history of slavery and race in America.

Earlier this morning residents of the city came out to celebrate Richmond Liberation Day.

The ceremony is to be held at the intersection of East Main and Nicholson streets. This is the location where Union soldiers, led by Black units, first entered the city on April 3,1865, ending Richmond’s role as the capital of the southern rebellion to keep Black people in bondage.

Love the subtle shade of "we're not celebrating your failure"

Sitting here at an event at the museum at Tredegar that's featuring the Elegba Folklore Society that is a celebration of the event, and thinking about this. Wondering what Hillary Green has come up with regarding the Emancipation Day celebrations in Richmond. I poked around a bit on it and there's a whole movement concurrent with MA going up, but I don't think it was all that enduring. The neat thing about that 1905 photograph on Main Street is that the central building on that block, right behind the streetcar, was the former U.S. Customs House that served as the Confederate War Department. Plus, if you zoom in, you can see mounted representatives of fraternal organizations in their regalia.

Was also thinking about how important words and perspectives are on this and how easy it is to get locked into a habitual way of putting things. For instance, the ABT's IG stories this morning read, "On this day... Confederate lines near Petersburg broke after a nine-month siege, resulting in the fall of the Confederate capital of Richmond, VA to Union forces." Nothing really wrong with that from a factual perspective, but what if they shifted focus, they could say, "On this day...United States armies broke the nine-month Siege of Petersburg, resulting in the flight of the Confederate government from Richmond, VA." I like that one better. We center Confederates too much and leave the US too often as passive abstractions on the margins.