Everyone is talking about birthright citizenship. Just a few months ago, before Donald Trump introduced the subject on the campaign trail, very few people had ever heard of it.

Trump promised to issue an executive order overturning birthright citizenship and has since done so after assuming office on Tuesday. I don't expect that this landmark piece of Reconstruction legislation, enshrined in the Fourteenth Amendment. On Thursday, Judge John C. Coughenour, a Reagan appointee, issued an order and offered the following: “I’ve been on the bench for over four decades. I can’t remember another case where the question presented is as clear as this one. This is a blatantly unconstitutional order.”

While the judge’s order is a relief to many, I suspect that Trump and his advisers anticipated the ruling. In other words, they likely don’t expect the Fourteenth Amendment to be overturned outright.

What Trump and his allies are hoping for is a continued whittling away at the idea of birthright citizenship by introducing the subject for public discussion and turning it into another political football—a move that will create room for Congress and the courts to dismantle as much of it as possible.

What they fear is any serious consideration of why birthright citizenship was considered so important by Republican lawmakers after the Civil War and how it has protected Americans ever since.

In short, they fear history.

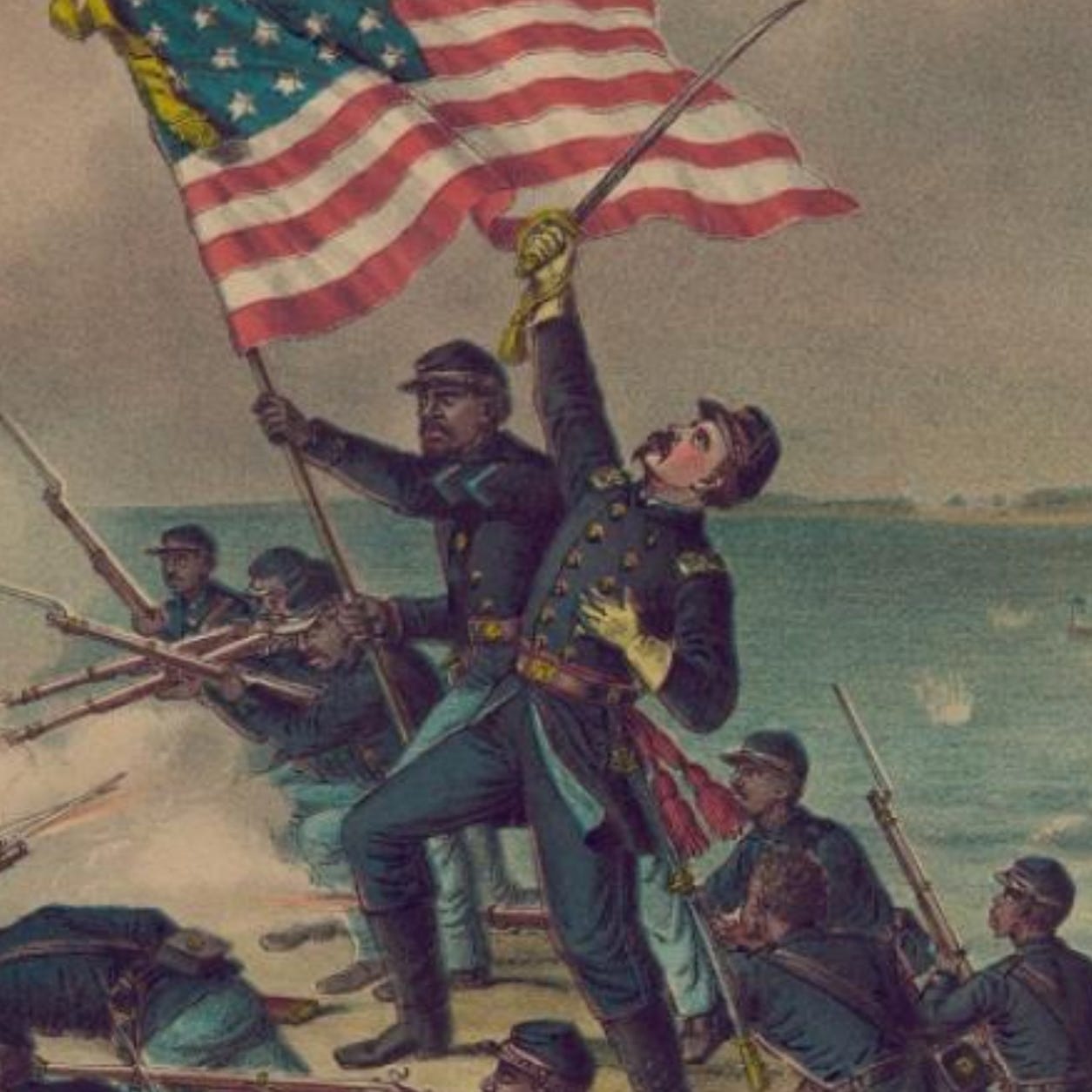

The Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed certain rights for African Americans in all the states, was enacted following the end of the Civil War in 1868 and sought to rectify the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Dred Scott decision, which ruled that only white people could be citizens of the United States. Among other things, the Fourteenth Amendment sought to ensure birthright citizenship for everyone born on U.S. soil regardless of race.

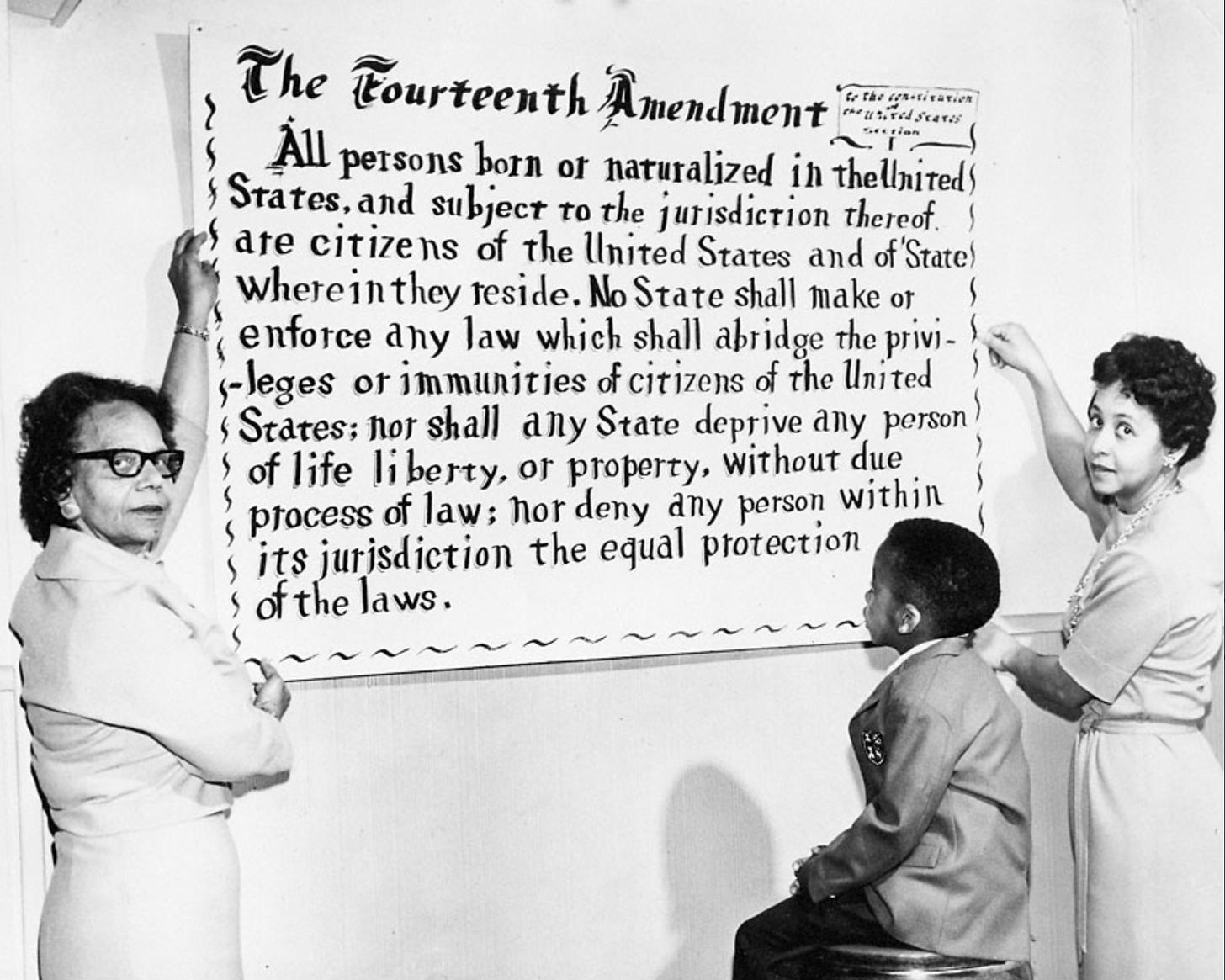

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment is crystal clear:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

While the fight for citizenship recognition continued well after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, the aim of the Amendment was to eliminate the existence of a class of people who were subjected to American law, but excluded from American legal rights and the protections they afforded.

It is important to recognize that this debate over citizenship preceded the Civil War as well. Martha Jones’s book Birthright Citizens is a wonderful resource with which to explore this longer history.

Consider the the 1844 New York court case of Lynch v. Clarke, which was one of the first cases to address the concept of birthplace-based citizenship in the United States, even though it did so in the context of deciding an inheritance in New York. Julia Lynch was born in New York to two Irish parents who were temporary visitors in the United States. Soon after her birth, Lynch and her family returned to Ireland without declaring an intent to be naturalized. Although she remained in Ireland for twenty years after her birth, a U.S. court later used her place of birth, to decide that she was an American citizen at the time of her birth.

The Court ruled—at a time of intense discrimination and violence against Irish Americans—that her prolonged residence in Ireland succeeding her birth did not affect her birthright citizenship in the United States. Judge Lewis Sandford wrote in 1844, “I can entertain no doubt, but that by the law of the United States, every person born within the dominions and allegiance of the United States, whatever were the situation of his parents, is a natural born citizen.” The Lynch case is one of the few examples of how courts at the time applied the basic principle of citizenship based on some people’s birth in the United States.

In 1898—thirty years after the Fourteenth Amendment had been ratified—the Supreme Court in the case United States v. Wong Kim Ark established the explicit precedent that any person born in the United States is a citizen by birth.

Wong Kim Ark was born in the United States to Chinese parents, though he frequently returned to China on temporary visits. When attempting to return to the United States in 1890, Wong Kim Ark was barred from entering the country under the Chinese Exclusion Act because under the law, Wong Kim Ark could be excluded from the United States based on his Chinese ancestry. However, the Supreme Court held in a 6-2 decision that because Ark was born in the United States, and his parents were not “carrying on business” or “employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China”—implying that these would be the only reasons Ark might not have counted as “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States—Ark was indeed a U.S. citizen.

While I suspect that most people today think about this debate over citizenship in connection to immigrants from Mexico and Central America, we need to recognize that the Fourteenth Amendment has protected a much larger swath of the American public over time.

This is about all of us.

Even a cursory understanding of this history and the text of the Fourteenth Amendment itself explains why the federal judge’s ruling was so decisive in response to Trump’s executive order.

It’s also a reminder of the problematic place of Reconstruction in our collective memory of American history. Generations of Americans learned to think of Reconstruction as a failed attempt to integrate African Americans into the nation as full citizens following the Civil War. Organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy approved textbooks and other materials that offered students a Lost Cause narrative of innocent white southerners at the mercy of “scalawags” and “carpetbaggers.”

Even academics of the Dunning School—a school of thought popular in the early twentieth century that was highly critical of Reconstruction—helped to reinforce a historical narrative defined by corruption and failure. Historian William Dunning offered the following assessment:

With the collapse of the Confederacy all the slaves became free, and the strange and unsettling tidings of emancipation were carried to the remotest corners of the land. As the full meaning of this news was grasped by the freedmen, great numbers of them abandoned their old homes, and, regardless of crops to be cultivated, stock to be cared for, or food to be provided, gave themselves up to testing their freedom. They wandered aimless but happy through the country, found endless delight in hanging about the towns and Union camps, and were fascinated by the pursuit of the white man’s culture in the schools which optimistic northern philanthropy was establishing wherever it was possible.

Dunning and others gave President Andrew Johnson high marks for his attempt to block civil rights legislation that included a provision for birthright citizenship, which was later included in the Fourteenth Amendment:

Johnson was soon obliged to confront another measure which was much more subversive than the Freedmen’s Bureau bill of his most cherished constitutional convictions. This was the Civil Rights bill, designed to secure to the freedmen through the normal action of the courts the same protection against discriminating state legislation that was secured in the earlier bill by military power. It declared the freedmen to be citizens of the United States, and as such to have the same civil rights ‘ and to be subject to the same criminal penalties as white persons; and it provided with great fullness for the punishment of any one who, under color of state laws, should discriminate against the blacks. It was a plain announcement to the southern legislatures that, as against their project of setting the freedmen apart as a special class, with a status at law corresponding to their status in fact, the North would insist on exact equality between the races in civil status, regardless of any consideration of fact. The constitutional questions involved in this measure were of the most profound and intricate nature, and the theory of citizenship which it embodied was such as to make conservative constitutional lawyers stare and gasp.

For countless others who were not subjected to this distorted picture of Reconstruction, the subject wasn’t taught at all or barely addressed. We have only barely begun to move away from this problematic interpretation of Reconstruction in our schools over the past few decades. We still have a long way to go.

There has never been a more important time to teach the history of Reconstruction and the importance of birthright citizenship at every level of education.

This perfect storm of ignorance of the past and and a super-charged political environment constitutes a perfect storm with which enemies of democracy like Trump and his allies need to dismantle one of the most important constitutional provisions that we have.

Reconstruction was a not a failure. Of course, we need to acknowledge and appreciate the extent to which the work that went into it was viewed as a threat by many white Americans, along with the violence and legal efforts taken to overturn many of its achievements that ushered in the era of Jim Crow.

But to reduce this period of history to one of failure helps to perpetuate the work of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Dunning School and anyone else who believes that this country was solely intended to be a ‘white-man’s nation.’

The defense of birthright citizenship and the Fourteenth Amendment constitutes nothing less than a defense of the United States as a bi-racial democracy—the belief that citizenship must not be determined by the color of one’s skin.

The question of birthright citizenship is not about other people. The Fourteenth Amendment protects all of us.

If people don't like section 1 of the 14th Amendment and "birthright citizenship," they have a constitutional remedy. Propose a constitutional amendment, send it out to the states, and try to get it ratified. The notion that any president, with the stroke of a sharpie, can just eliminate part of the constitution should terrify every last one of us.

Thank you for writing this! The amount of Reconstructionist History going on today is mind boggling... FL putting in their middle school curriculum that "slaves learned valuable skills" was absolutely appalling.