On January 1, 1863 Boston’s abolitionist community gathered on a cold, cloudy, and gloomy day in anticipation of the news that Abraham Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

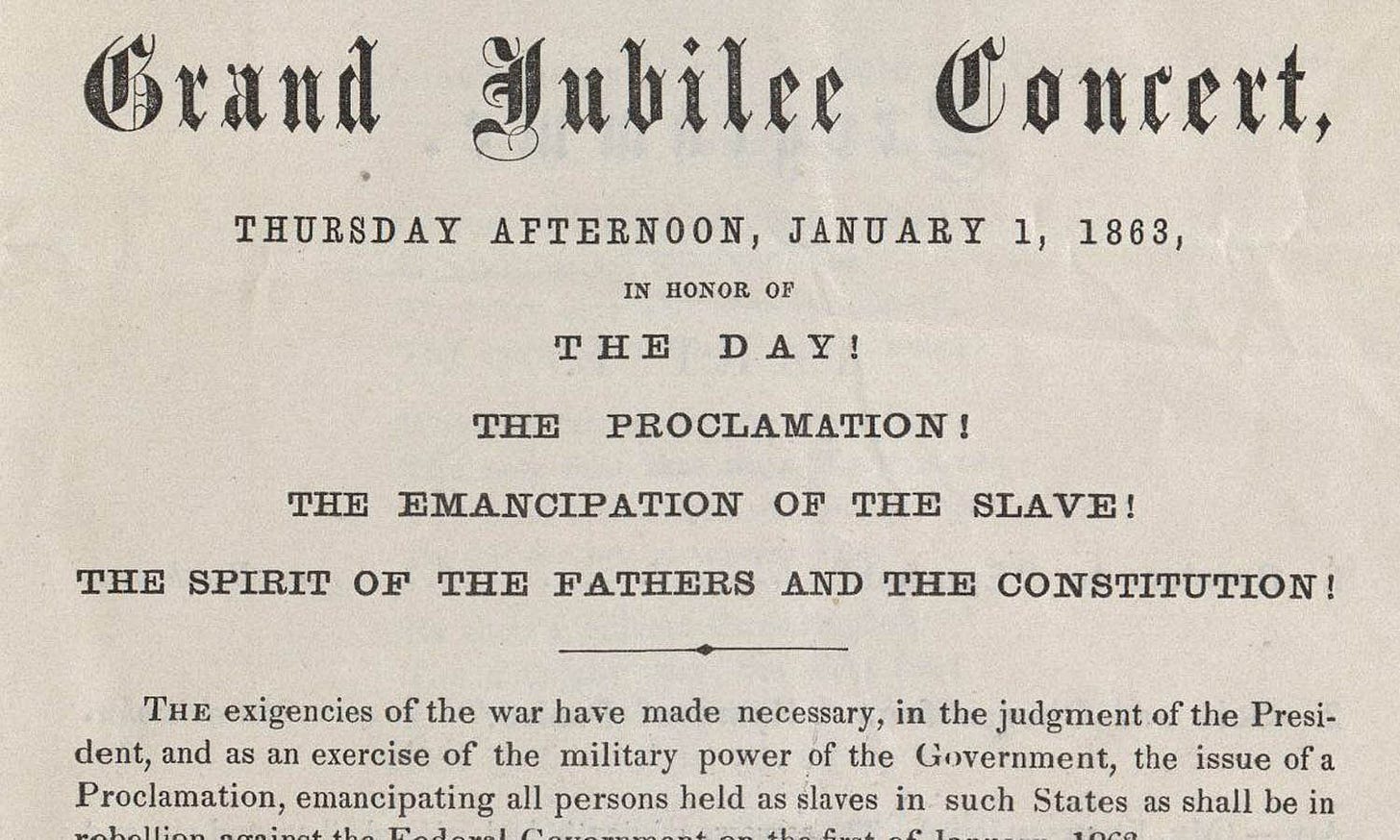

At Boston’s Music Hall the orchestra played Mendelssohn’s Hymn of Praise and Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony for the city’s elite that included literati such as Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The program for the event boasted “that this first day of the new year will prove the complement of the 4th of July 1776, and a new era in the history of the Republic, when the soil of America, hallowed anew by the sacrifice of so much heroic blood, shall no longer be trodden by the foot of a slave.” When word arrived that Lincoln had indeed signed the proclamation a “storm of enthusiasm followed…. Shouts arose, hats, and handkerchiefs were waved, men and women sprang to their feet to give more energetic utterances to their joy.”

Across town at Tremont Temple, located across the street from Park Street Church, where William Lloyd Garrison delivered his earliest abolitionist speeches, Frederick Douglass joined fellow Black abolitionists William Wells Brown, William Cooper Nell, Rev. Leonard Grimes and Charles Lenox Remond, along with a crowd that was estimated at three thousand. Garrison, once a close mentor and now rival of Douglass, chose to remain at Music Hall, thus avoiding an uncomfortable encounter on what promised to be a joyous occasion. Douglass’s anxiety grew with each passing hour as the crowd increased in size and cheered the many speeches delivered that day. He knew that there was always the chance that Lincoln would back down from signing the proclamation. Perhaps the Confederacy had agreed to return to the Union in the final hours of 1862 or Lincoln’s own understanding of military necessity might have shifted rendering the proclamation unnecessary or even counterproductive in his mind. “Every moment of waiting chilled our hopes, strengthened our fears.”

Finally, “a face fairly illumined with the news he bore, exclaimed in tones that thrilled all hearts, ‘It is coming!’ It is on the wires!’” Douglass and the crowd could barely contain themselves upon the realization that Lincoln had kept his promise. “Joy and gladness,” Douglass wrote, “exhausted all forms of expression from shouts of praise to sobs and tears.” After midnight the crowd moved across the Boston Common to continue the celebration at Grimes’s Twelfth Street Baptist, which had served as a shelter for numerous freedom seekers.

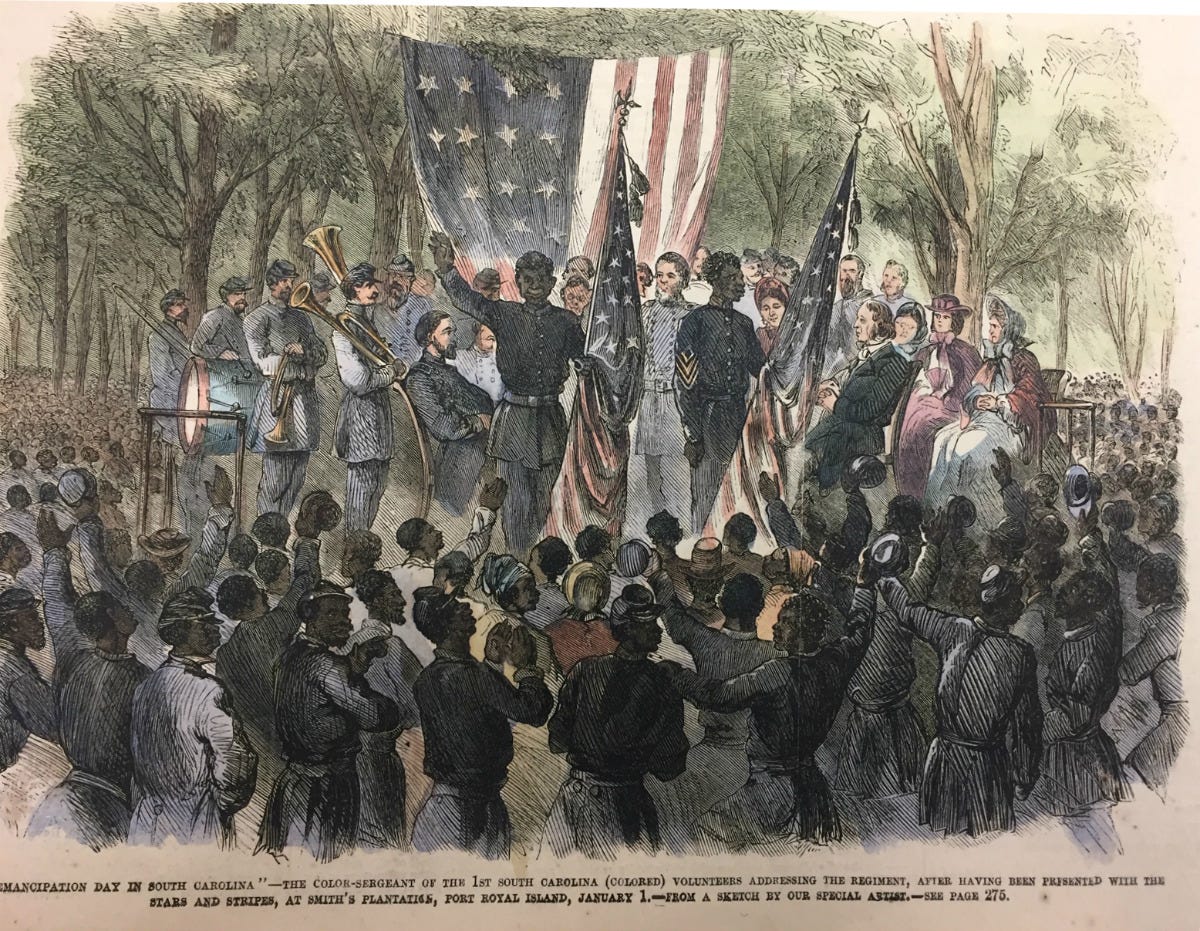

One thousand miles south in Port Royal, South Carolina, a large interracial crowd gathered at Camp Saxton, which served as the training ground for the all-Black 1st South Carolina Volunteers. The roads “were thronged” with visitors that included military officers and other dignitaries as well as many of the teachers and other reformers, who traveled to the Sea Coast Islands to work with the thousands of formerly enslaved men, women, and children after the Union navy occupied the area in November 1861.

Charlotte Forten, a young Black school teacher from Salem, Massachusetts took a ferry from St. Helena Island to take part in the festivities. “As I sat on the stand looked around on the various groups,” she later recalled in her diary, “I thought I had never seen a sight so beautiful. There were the black soldiers, in their blue coats and scarlet pants, the officers of this and other regiments in their handsome uniforms, and crowds of lookers-on, men, women and children grouped in various attitudes, under the trees. The faces of all wore a happy, eager, expectant look.” Silence hung over the crowd as Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was announced.

Regimental flags were presented to Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson and his 1st South Carolina Volunteers. Higginson was moved by the ceremony, he recalled, but what followed was “so utterly unexpected and startling.” Almost on cue, the largely Black audience began singing ‘My Country tis of Thee.’ Higginson was moved to tears: “I never saw anything so electric; It made all other words cheap; it seemed the choked voice of a race at last unloosed. Nothing could be more wonderfully unconscious; art could not have dreamed of a tribute to the day of jubilee that should be so affecting; history will not believe it; and when I came to speak of it after it ended, tears were everywhere.”

The celebrations at Camp Saxton continued well into the evening. For Forten it had been a “grand, glorious, day,” one that justified a cautious optimism about the future. “The dawn of freedom which it heralds may not break upon us at once,” she anticipated, “but it will surely come, and sooner, I believe than we have ever dared hope before.

Many Black and white Americans anticipated and celebrated Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Few could have imagined such a moment just a few short years earlier, but all these years later, Lincoln’s decision has increasingly been questioned.

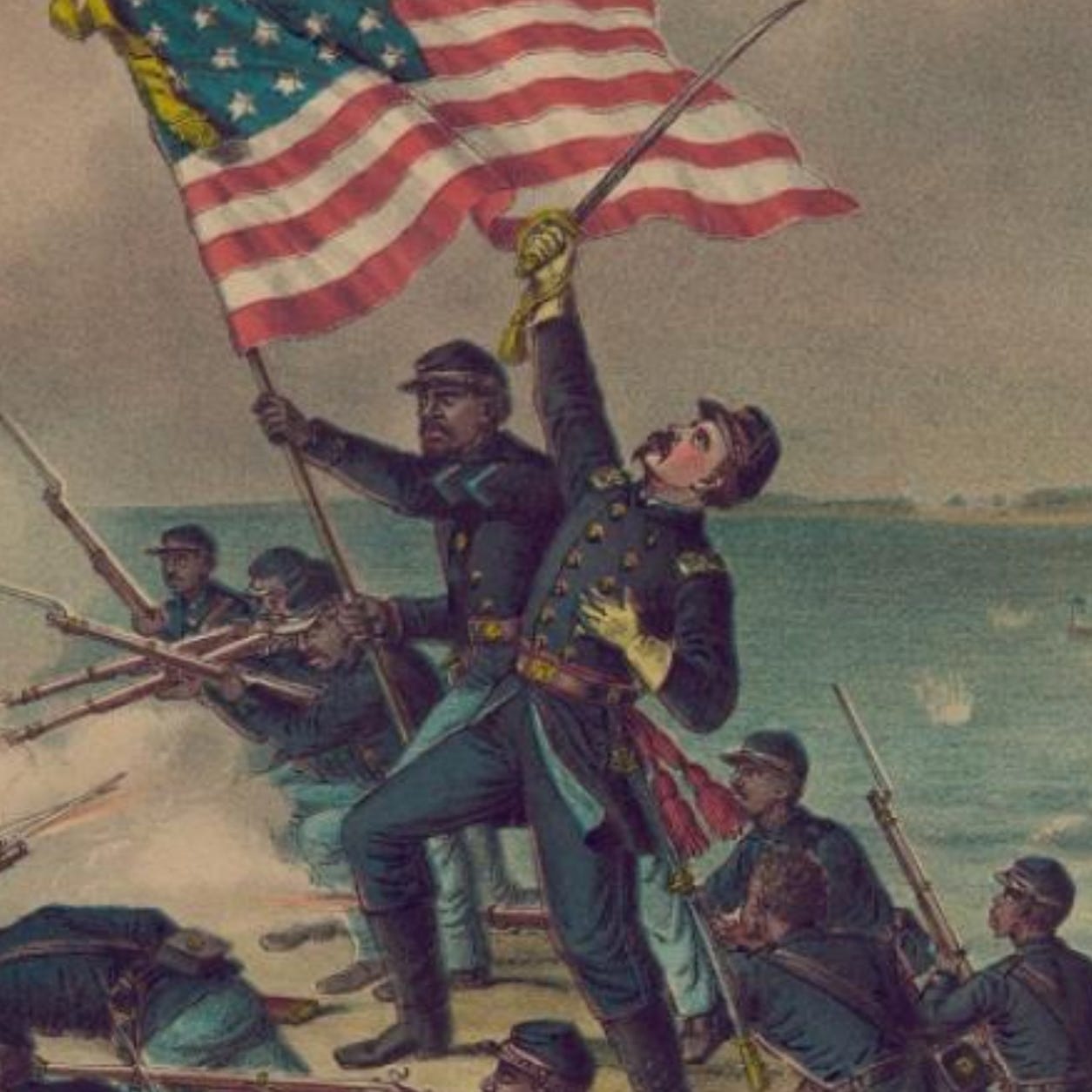

One popular avenue of attack is to suggest that the proclamation did not immediately free any slaves in the South. This is a curious criticism given the fact that the proclamation turned every Union army into a liberating army regardless of how the men in the ranks and their commanders viewed emancipation and African Americans. Armies increasingly became beacons of hope as enslaved people learned of the proclamation and signaled their approval by running away from plantations and claiming their freedom.

Historian Bennett Parten suggests in his new book on Sherman’s March, which took place in November 1864, that upwards of 20,000 enslaved men, women, and children may have followed his army east toward Savannah.

The Emancipation Proclamation was essential in helping to seal the defeat of the Confederacy and end slavery. It was arguably the most radical military order issued by Lincoln during the war.

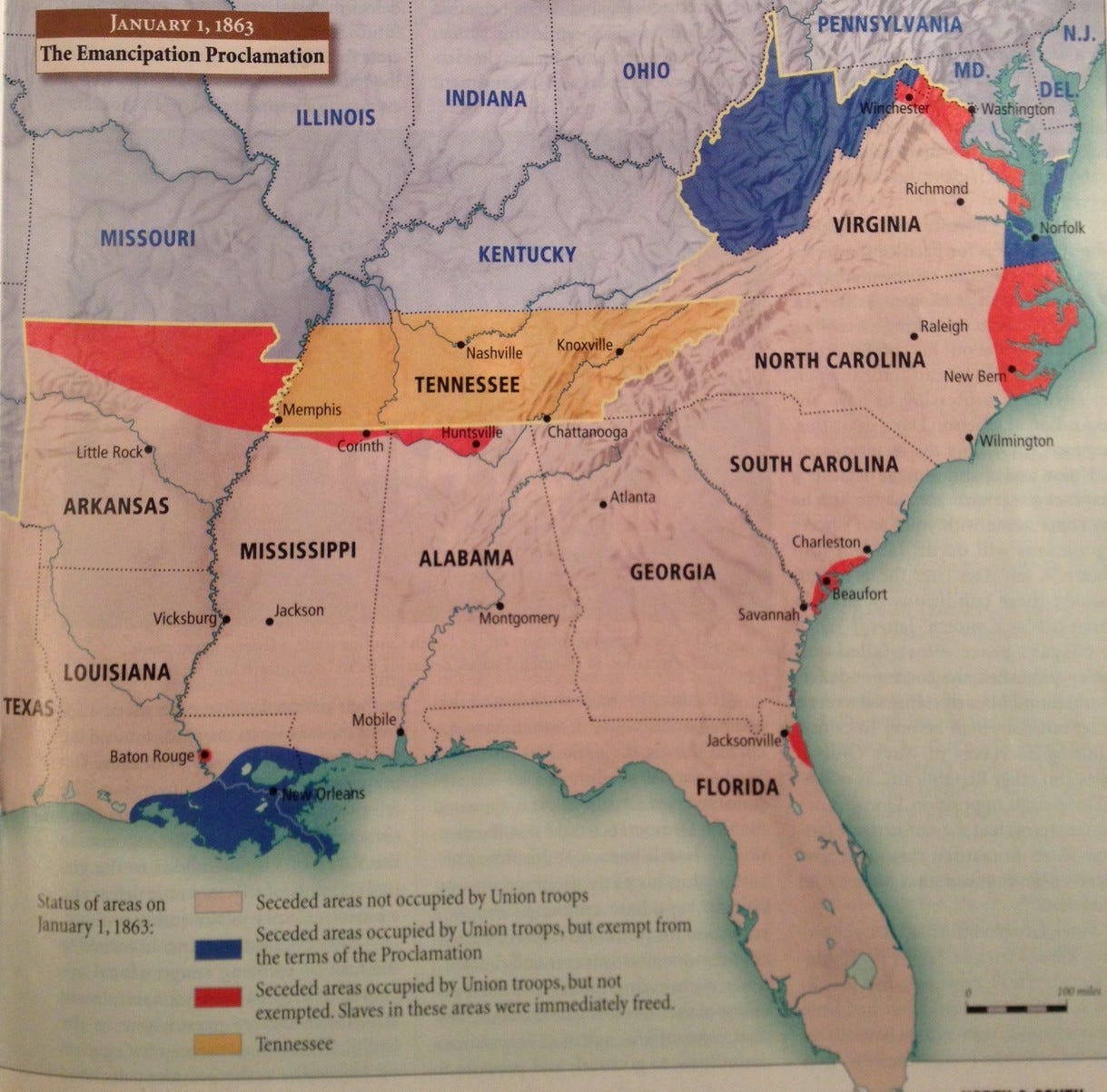

But the claim that the proclamation didn’t itself immediately free enslaved people is itself mistaken. As you can see by the following map. Thousands of slaves were freed on January 1, 1863, many of whom would go on and volunteer to fight against the Confederacy.

Areas exempted, included Tennessee, which was then under Union occupation and the soon-to-be state of West Virginia, which was still part of the Reorganized (pro-Union) Government of Virginia. But in parts of Arkansas, northern Mississippi and Alabama, along with northern Virginia, Norfolk, much of the eastern coast of North Carolina, the Sea Islands of South Carolina, and a small section of Florida, enslaved people celebrated January 1 as a day of liberation.

The Emancipation Proclamation fundamentally transformed the lives of countless numbers of enslaved people and that of the nation as a whole. The war did not have to end with the abolition of slavery. There was nothing inevitable about the end of slavery during the war.

Understanding why it ended and what it means to us all these years later involves first getting the history right.

Just a quick note that I had to ban a reader today for abusing the comments section. Please stay on topic and please don't use this space simply to push your own agenda. Thank you.

Teach in NE North Carolina and I make it a point to refer to Jan 1 as Emancipation Day in my classes. The number I see often is around 40-50,000 were freed on Jan. 1. Most of my students are familiar with Juneteenth but this is always a good lesson for them.