The Curious Case of Charley Benger

A community in Georgia hopes to dedicate a plaque honoring a Black Confederate.

In 2018, two Republicans state congressmen proposed legislation that would create a monument honoring the state’s Black Confederates to be located on the capital grounds. That proposal was roundly defeated.

Recently, the Macon-Bibb County commissioners in Georgia approved a plaque that would honor one so-called Black Confederate musician by the name of Charley Benger. Macon’s mayor Lester Miller rejected the proposal claiming that he needed to see additional information from the local NAACP and United Daughters of the Confederacy, who are behind the project.

As was the case in South Carolina, this project comes at a fraught moment in the debate over the public display of Confederate symbols. The proposal in South Carolina came just two years after the removal of the Confederate flag from the state house grounds following the heinous murder of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston by a self-proclaimed white supremacist.

Similarly, in 2022 the city of Macon removed two Confederate monuments from their downtown locations.

So, why does the local UDC believe that Charley Benger is worthy of a plaque? The answer has everything to do with the decades-long campaign by Confederate heritage organizations to get the Confederacy right on the issue of race and slavery. If African Americans supported the Confederacy in significant numbers, then it makes little sense to argue that its bid for independence was wrapped up in the defense of slavery.

As I argue in my book, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth, this has involved a massive effort, since the 1970s, to highlight stories of loyal slaves and free Black men through a misreading of primary sources and the failure to come to terms with a massive amount of scholarship on the Confederacy and slavery.

Unfortunately, in doing so the very organizations and individuals that claim to be standing up for these men (who in many cases have indeed been lost to history) have done the most to distort their stories.

Charley Benger is just one of many examples.

It will come as no surprise that we know very little about this free Black man.

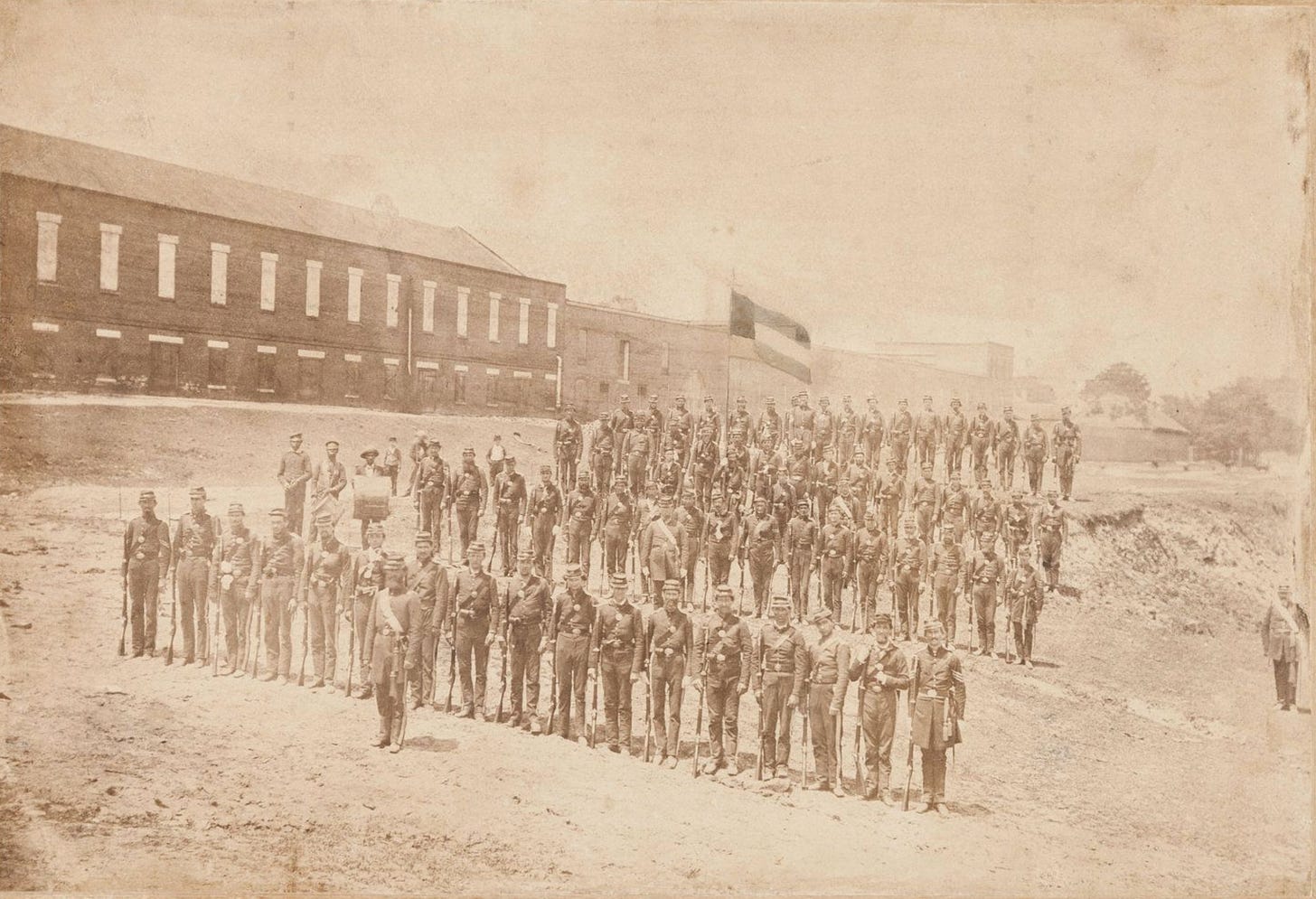

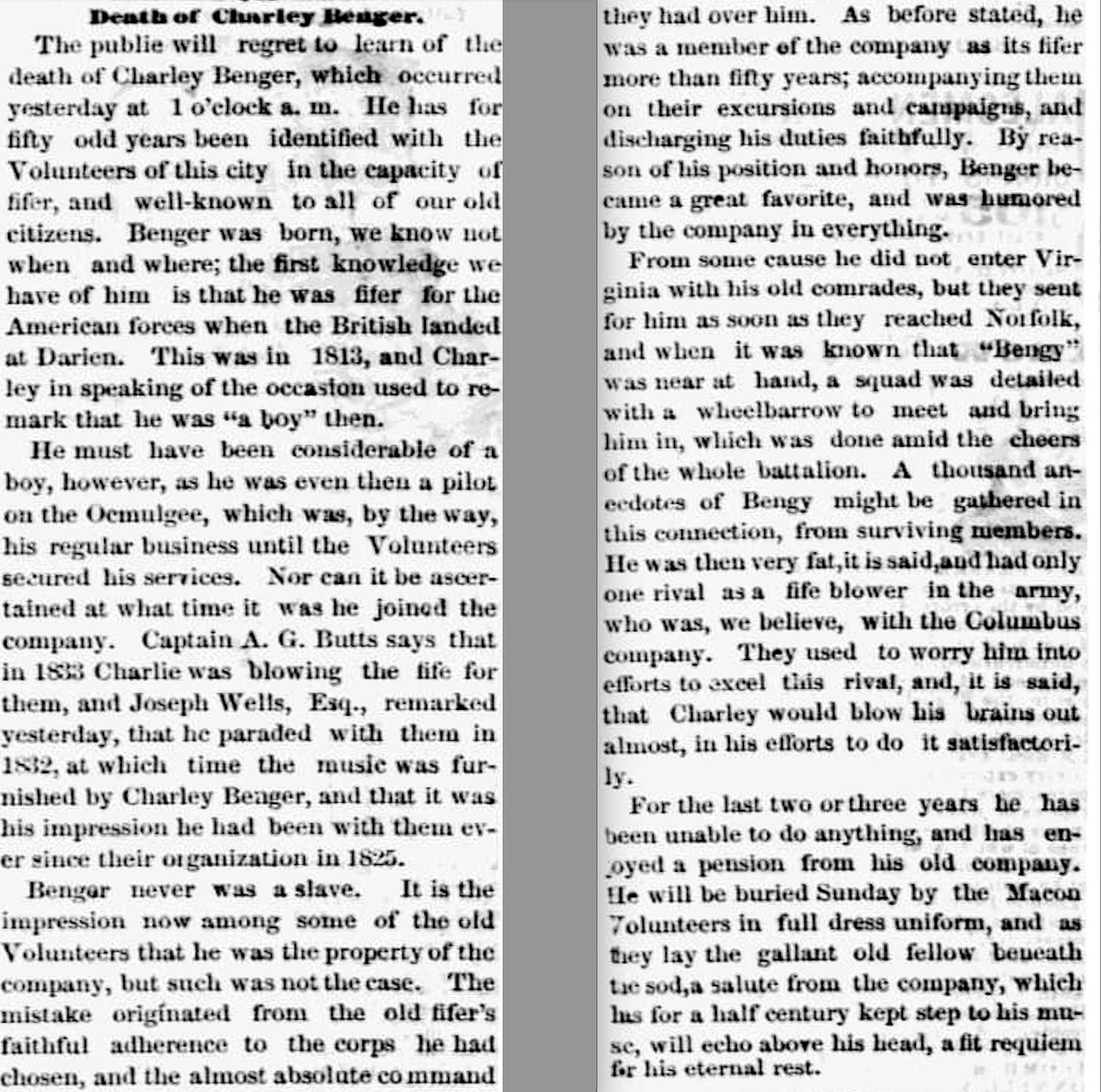

Charley’s date of birth is unknown. He first appears in the historical record as a “fifer” for a volunteer militia company in Macon, Georgia that fought during the War of 1812. According to a newspaper announcing Charley’s death in 1880, he was also a pilot on the Ocmulgee River. This same newspaper reported that after the war Charley remained with the company throughout the antebellum period, mustering with the unit as a musician.

There can be little doubt that Charley formed a close relationship with the men in this company over the ensuing decades. Why he maintained such a close connection with the men in the company must remain conjecture, but Charley likely saw some benefit to remaining in the good graces of the community’s white population.

Life for free Blacks in Georgia and other Southern slave states was precarious at best. By the end of the antebellum period, the future for free blacks in Georgia was in grave doubt. As an editorial in the Daily Intelligencer—an Atlanta newspaper—noted on January 9, 1860: “We are opposed to giving free negroes a residence in any and every Slaveholding state, believing as we do, that their presence in slave communities is hurtful to the good order of society, and fraught of great danger to our ‘peculiar institution.’”

When the Macon Volunteers marched off to war as part of the 2nd Georgia Battalion at the beginning of the Civil War, Charley was unable to join them.

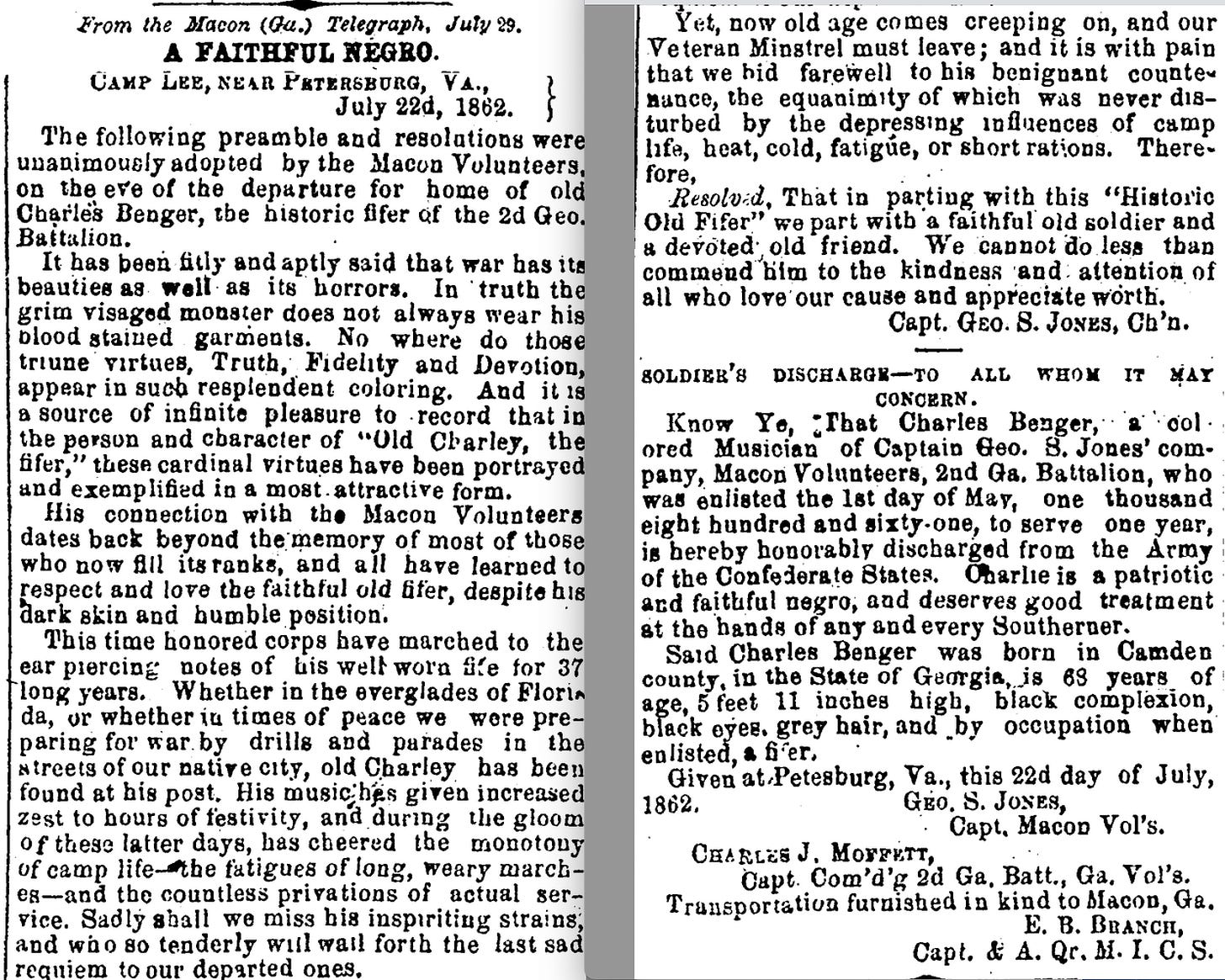

Though some regiments utilized Black musicians from the beginning of the war, it was not until 1862 that the Confederate army formally enlisted cooks and musicians on a larger scale. It is unclear as to whether Charley was paid, but most of these men were, though they almost certainly were not armed or uniformed.

Confederate regulations are crystal clear in their distinction between cooks and musicians and enlisted soldiers. At no point during the very public debate over the enlistment of Black men as soldiers in 1864-65 did someone point to the many Black musicians and cooks as evidence that Black men were already serving as soldiers.

The Macon Telegraph captured the moment that Charley joined the company.

From some cause he did not enter Virginia with his old comrades, but they sent for him as soon as they reached Norfolk, and when it was known that ‘Bengy’ was near at hand, a squad was detailed with a wheelbarrow to meet and bring him in, which was done amid the cheers of the whole battalion. A thousand anecdotes of Bengy might be gathered in this connection, from surviving members.

In July 1862 Benger left the unit to return home owing to his age and weight. The Macon Telegraph noted Benger’s “discharge” though it was clearly not an official Confederate discharge. It is important to point out that at no point was he described as a soldier. The pension that he is reported to have been paid was not in any way for his service to the Confederacy, but was likely a private fund organized by veterans of the company.

His obituary offers insight into how he was perceived by both the veterans and broader white community.

His connection with the Macon Volunteers dates back beyond the memory of most of those who now fill its ranks, and all have learned to respect and love the faithful old fifer, or “Veteran Minstrel” despite his dark skin and humble position.

Such a description suggests that while many of the men held Charley in great affection, they also thought of him as something akin to a mascot. Ascribing the virtues of “Truth, Fidelity and Devotion” to Charley reinforced the paternalistic outlook and a racial hierarchy of white supremacy for the men in the company as well as readers back home.

As is the case with most of these so-called Black Confederates we learn nothing about how Charley viewed the long expanse of time he spent with this company; how he viewed the Confederacy; and what he thought about the end of slavery and the emancipation of four milion enslaved people.

There is an interesting story that could be told about Charley Benger’s long life, but in the hands of the UDC and others invested in the Lost Cause we are never going to get it.

Ultimately, Charley funcations as little more than a tool that allowed white Southerners to distance their failed bid for independence from the preservation of slavery by claiming that the majority of the enslaved and free Black population remained loyal to the Confederacy and the racial status quo.

Now, their descendants are committed to doing the same.

Any monument or plaque connecting Charley Benger to the Confederacy or referring to him as a Black Confederate would be a gross distortion of history.

It takes a historian who's studied the "issue/topic" of Black Confederates to insightfully examine this particular case. Liars of the Lost Cause invented the myth, and in Macon were apparently trying to perpetuate it.

So, the mayor put the ki-bosh on this? I'd certainly like to have seen the NAACP's input!

("Macon’s mayor Lester Miller rejected the proposal claiming that he needed to see additional information from the local NAACP and United Daughters of the Confederacy, who are behind the project.") Otherwise, I'm glad.

Nearly 50 years ago, I was a civil rights officer (civilian) at the Presidio of San Francisco. That was in its closing days as an Army base before it underwent its slow transformation into a National Park. From time to time, I sat on promotion panels for civilian jobs; my role was to ensure there was no bias in the deliberations. I recall a particular one.

The panel was evaluating candidate quals for an administrative-level vacancy. The panel, besides me, included about four, officers and employees. Uniformed military officers worked in an up-or-out system; as the Army was drawing down from its Vietnam involvement, the "out" portion (you got promoted or you were probably going to be forced out of the service) was dominant. One of the panelists was a self-confident junior officer who commented that one particular candidate could certainly NOT be very qualified: he'd been a "cabin boy" for 20 years so what kind of sharp, go-getter could he possibly be?

This woke me up. The candidate was Pilipino and served when foreign nationals were relegated to the menial jobs. He was performing the only job he was allowed to perform, all those 20 years. Sound familiar?

I explained that this is the reason: that candidate was in a no-advancement job. This was a major surprise to everyone. Had I not been an Asian American civil rights officer, I most certainly would not have known of this military personnel law. I don't know who was chosen by the selecting supervisor, but the Pinoy was unanimously included in the final group of best-qualified applicants.

Likewise, KML's intensive scholarship made him fairly unique to know the fallacious lie invented, of the many loyal Black Confederate soldiers.

(Ironically, much later, I learned that my Japanese grandfather had been a cabin boy on the USS Kearsarge in New York harbor in 1904. He got promoted to mess cook, so Naval regs were a bit different than those the Pinoy of my panel experience.)

My friend, you continue to fight the good fight on this issue, for which we should all be grateful.