The Crater Battlefield, the Power of Place, and Historical Memory

Yesterday I asked readers to share their favorite Civil War battlefield. Today I share mine.

A good friend of mine, who recently retired from the National Park Service, once suggested that the United States has preserved more battlefield land than every other nation combined in the history of the world. That’s a striking claim and one that I suspect is true. It says something about how we see ourselves as Americans and what we value in our efforts to preserve the past for future generations.

Battlefields connected to the American Civil War certainly make up a significant percentage of the total number of acres preserved. Yesterday, I asked all of you to share your favorite battlefield and even the specific spot on that battlefield, where you feel the most connected to the past. Thanks to those of you who commented.

Many of you who have followed my work over the years won’t be surprised to learn that, for me, it’s the site of the battle of the Crater, located on the Petersburg National Battlefield in Petersburg, Virginia. I’ve spent countless hours walking this battlefield with family, friends, and varous tour groups. It is also the subject of my first book published back in 2012.

I’ve led numerous tours of the Crater that focus on both history and memory. Unfortunately, I haven’t been back since I delivered a keynote address on the 150th anniversary of the battle back in 2014. With everything that has happened in the past few years, I don’t know how I would go about interpreting this battle in 2022.

First things first.

1864

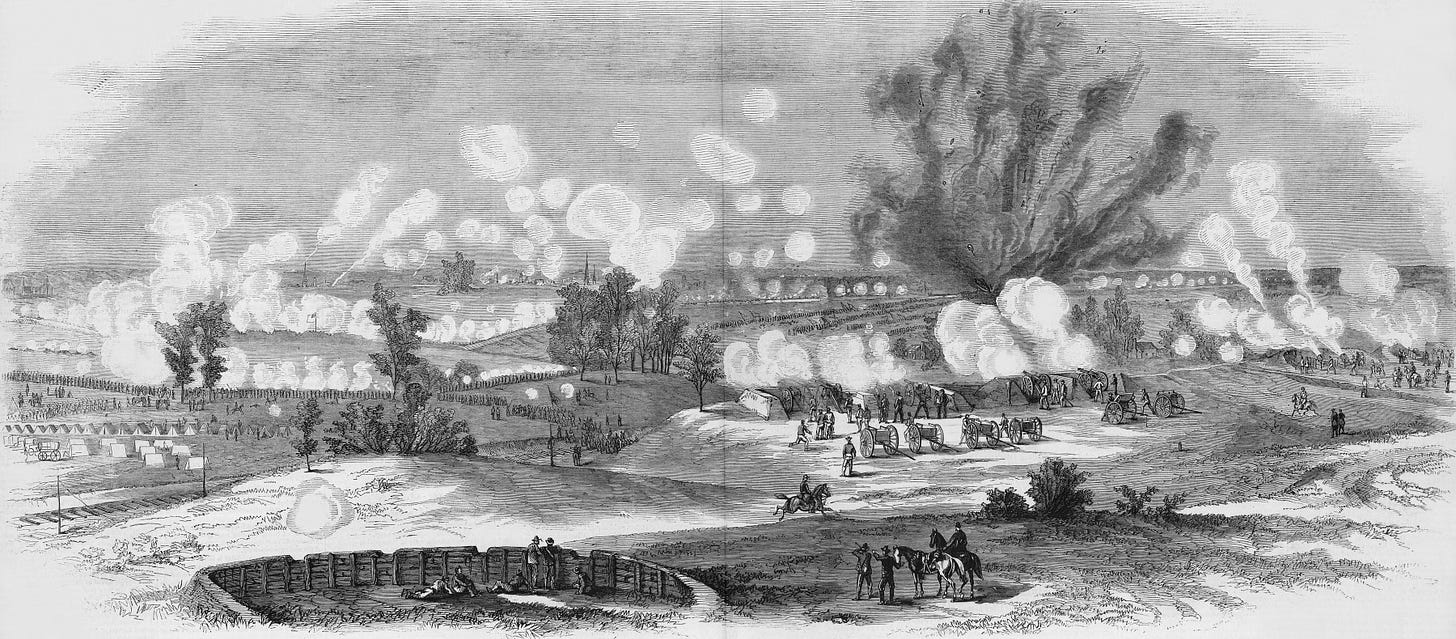

The battle that took place on the early morning of July 30, 1864, just east of the city of Petersburg, is best remembered for the detonation of roughly 8,000 pounds of black powder located underneath a Confederate salient. The explosion, which followed the construction of a mine that eventually measured roughly 510 feet, was intended to punch a hole in the Confederate line followed by an advance of four divisions of United States soldiers from the Ninth Corps. The goal was to break the Confederate line, take control of the city, and end what many were coming to view as a “siege.”

The initial explosion crippled a regiment of South Carolinians positioned directly atop the mine. Union soldiers poured into the complex chain of Confederate earthworks that dotted the landscape. The first three divisions made steady progress, but it was a division of United States Colored Troops, under the command of Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero, that pushed furthest into the Confederate works. By roughly 9AM they were poised to make a final advance that would likely secure a victory.

There are a number of places to stop and consider the fighting that took place that day. The reconstructed entrance of the mine gives you a sense of just how close the two armies were to one another during this part of the campaign and during the construction of the mine.

Many visitors are disappointed to see that so little of the actual crater remains. The site was preserved for decades after the war, but much of the battlefield was turned into an 18-hold golf course at the beginning of the twentieth century. What was left of the crater itself was maintained and visitors were allowed to dodge golf balls to see it for themselves.

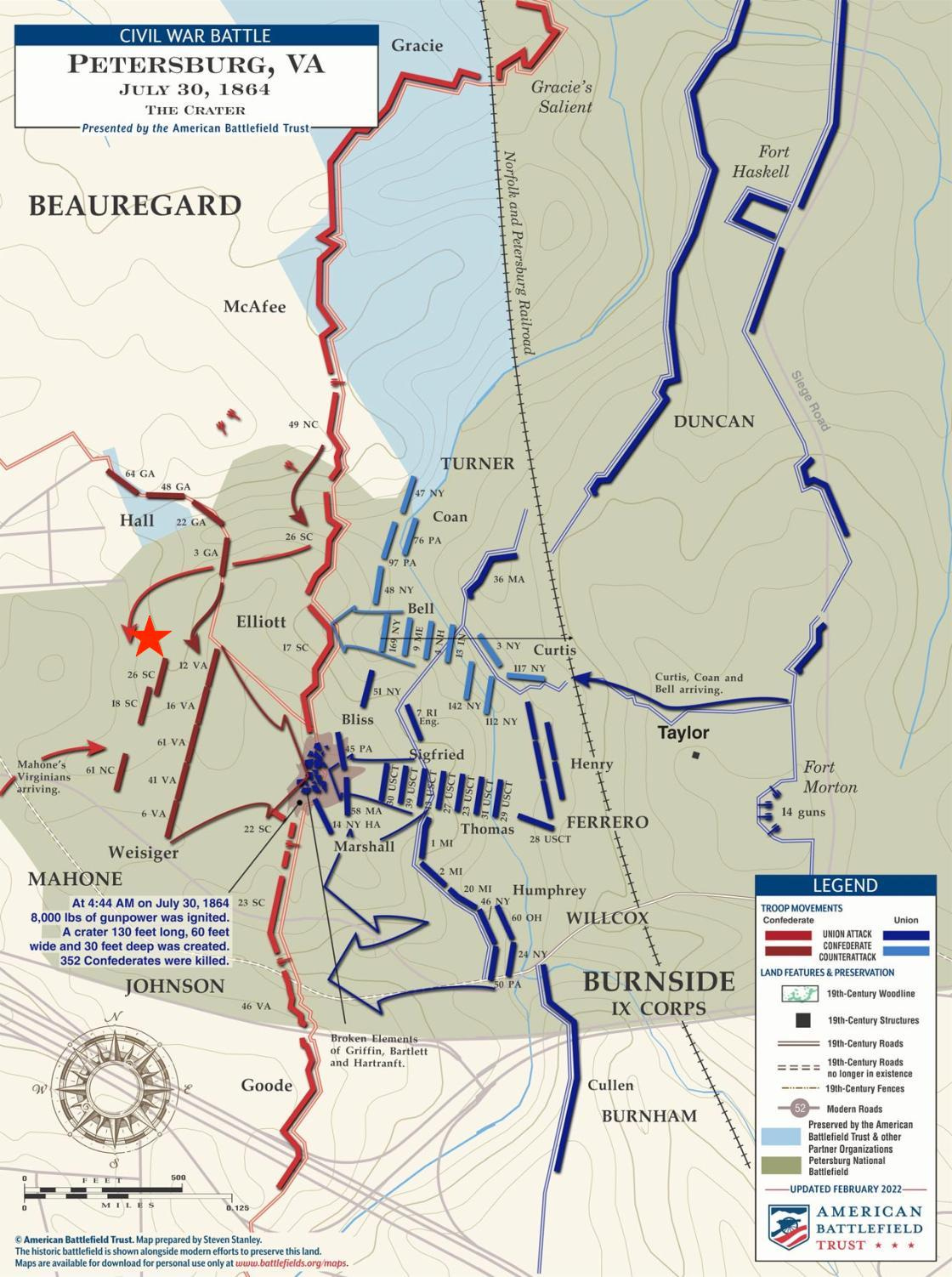

My favorite spot on the battlefield is just off the Jerusalem Plank Road in a depression that empties in a field just a few yards from the crater. [I placed a red star on the map below for your reference.] It is from here that the division of Confederate general William Mahone was positioned to launch a counterattack against the advance elements of the Union assault, including the Black soldiers.

Mahone’s division—made up of four brigades from Georgia, Alabama, Florida, and Virginia—took advantage of this depression that extended down from an area known as Blandford, located just a few hundred yards northwest of the crater.

Five regiments of Virginians were the first to position for the counterattack at 9AM. It is here where the men were informed that the Union attack included Black soldiers. Apart from a few skirmishes at the beginning of the Overland Campaign in early May 1864, this was the first time that men from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia would come face to face with a large number of Black soldiers on the battlefield.

It’s a pivotal moment for these men. They were defending what was left of a civilian population in Petersburg. Many of the Virginians were born and raised in eastern Virginia, from counties with significant slave populations. Mahone himself was born and raised in Southampton County, where Nat Turner launched his failed insurrection in 1831.

From this position I can easily imagine the fury that animated these Confederates as they were about to commence their attack. If I walk toward the crater from this spot I walk straight into what is left of one of the most violent scenes of the entire war. By 2PM Confederates had managed to retake the line, including the crater, and had massacred upwards of 200 Black soldiers.1

Their letters and diaries are filled with vivid descriptions of what it was like to shoot and club these men to death rather than allow them to surrender. Confederates viewed Black soldiers as slaves in rebellion and treated them as such.

Colonel William Pegram captured the thoughts of many of his comrades when he wrote to his sister a few days later:

There were hardly less than six hundred dead—four hundred of whom were negroes. As soon as we got upon them, they threw down their arms to surrender, but were not allowed to do so. Every bomb proof I saw, had one or two dead negroes in it, who had skulked out of the fight, & been found & killed by our men. This was perfectly right, as a matter of policy. I think over two hundred negroes got into our lines, by surrendering & running in, along with the whites, while the fighting was going on. I don't believe that much over half of these ever reached the rear. You could see them lying dead all along the route to the rear. While there was a temporary lull in the fighting, after we had recaptured the first portion of the line, & before we recaptured the second, I was down there, & saw a fight between a negro & one of our men in the trench. I suppose that the Confederate told the negro he was going to kill him, after he had surrendered. This made the negro desperate, & he grabbed up a musket, & they fought quite desperately for a little while with bayonets, until a bystander shot the negro dead.

It seems cruel to murder them in cold blood, but I think the men who did it had very good cause for doing so. Gen. Mahone told me of one man who had a bayonet run through his cheek, which instead of making him throw down his musket & run to the rear, as men usually do when they are wounded, exasperated him so much that he killed the negro, although in that condition. I have always said that I wished the enemy would bring some negroes against this army. I am convinced, since Saturday’s fight, that it has a splendid effect on our men.

Confederates didn’t shy away from admitting to their deeds during and after the battle. They maintained that it was entirely justified. More importantly, they wanted their loved ones back home to understand what was at stake now that the United States had armed Black men. The site of these men reaffirmed for slaveowners and nonslaveowners of the importance of maintaining slavery.

If walking toward the crater forces a confrontation with history, then tracing the route that Mahone’s men took that morning to arrive on the battlefield will place you in the middle of one of the most important sites of Civil War memory at Blandford Cemetery. [Start at the star on the map and look directly north to where the 62nd GA is positioned. That’s Blandford.]

Roughly 30,000 Confederate soldiers—many of them unidentified—are buried in Blandford Cemetery. Some of the earliest celebrations of Confederate Memorial Day took place at Blandford. In recent years, the Sons of Confederate Veterans has met annually to honor Richard Poplar, who they claim as a bona fide Black Confederate soldier. [They even dedicated a gravestone, though no one knows where in the cemetery Poplar is buried.]

William Mahone, who led the Confederate counterattack and helped secure victory that day is buried in the cemetery. I’ve always wondered if the lone “M” that marks his tomb reflected his unpopularity during the postwar period as a result of his role as leader of the Readjuster Party—the most successful bi-racial third party in nineteenth-century America.

1910

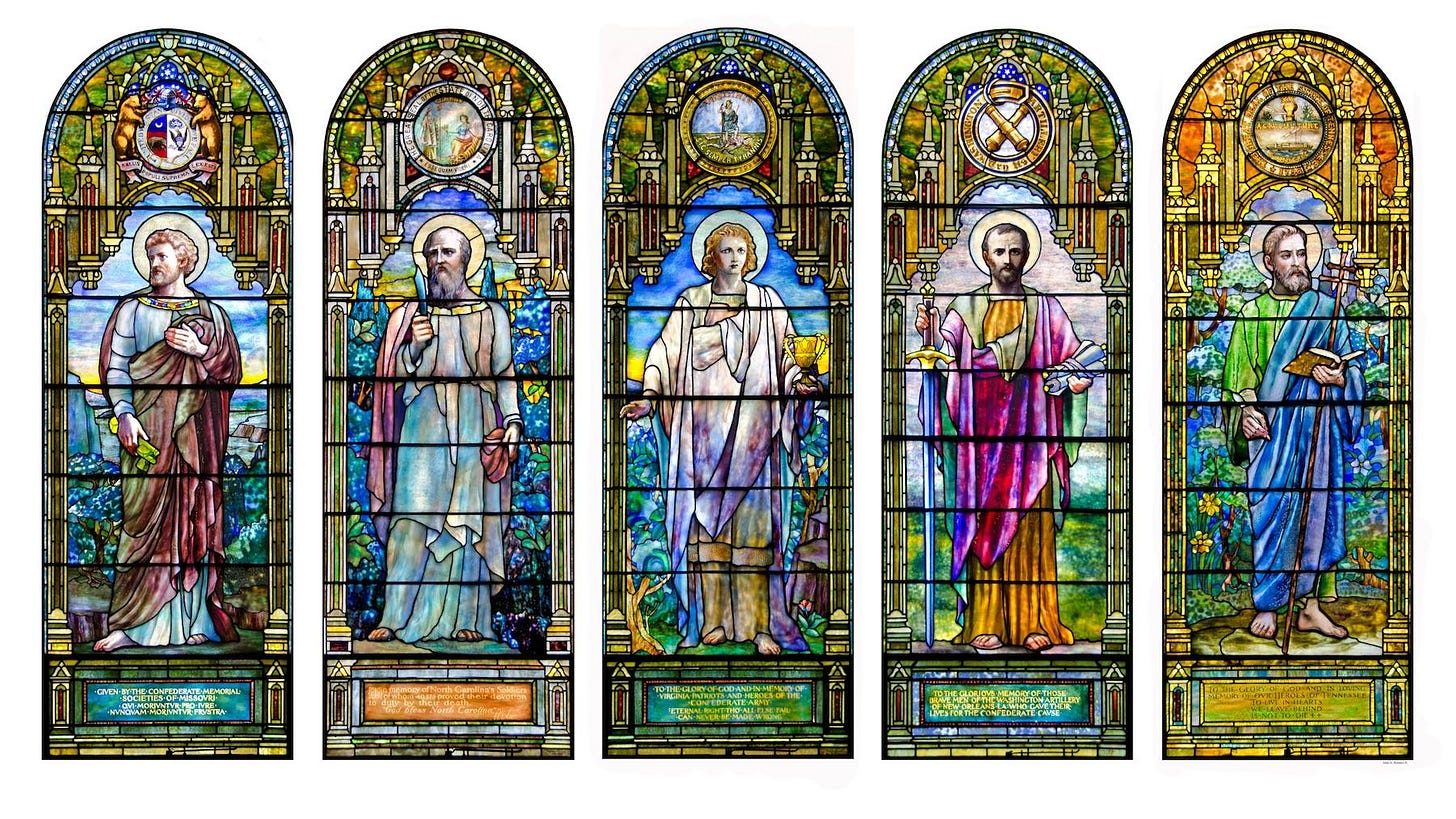

Then there are the Tiffany Windows inside Blandford Church. The church itself was constructed in 1735 and served as a hospital during the war. Beginning in 1889 the Ladies Memorial Association of Petersburg transformed the site into a shrine to the Lost Cause.

Kaylie Rideout writes:

A representative from the newly named Tiffany Studios was sent to survey the site and decided that there would be 14 windows—one to represent each of the 11 Confederate states and one each for Maryland, Arkansas, and Kentucky—as well as a lunette window commemorating the Petersburg Ladies. Kentucky’s Confederate memorial organization was unable to financially commit to the project, and records of the Ladies Memorial Association of Petersburg indicate that Tiffany Studios supplied an alternate window, a Cross of Jewels, as a gift to replace the vacated space. Each compass window was crafted in the Gothic Revival style with the state seal, a figure of one of Christ’s apostles, and an individualized inscription supplied by the state. The windows depicting South Carolina as St. Mark, Alabama as St. Andrew, and Virginia as St. John are some of the more visually rich examples of the way this commission married church, state, and the Confederate cause.

The project was completed on June 3, 1910, on the anniversary of the birth of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

According to historian Caroline Janney:

By transforming the old Blandford Church into a Confederate chapel, the Ladies had appealed to a national memory of the war dead that invoked an otherworldliness—an eternal life for the martyrs of the Lost Cause. Like many defenders of the Confederacy, they moved beyond death to celebrate the triumphs of not only their ancestors, but also of themselves. They had created an enduring landmark, a shrine to the Confederate dead, to be forever associated with the Ladies’ Memorial Associations. (pp. 187-88)

Standing on that spot back on the battlefield I am pulled in both directions. A visit to the Crater battlefield is incomplete without spending some time at Blandford Cemetery and vice-versa.

On that hot July day in 1864 the war played out in all of its racial ugliness. Just a few decades later at Blandford Cemetery the massacre of Black men was all but erased and the Confederacy itself was transformed into a righteous cause with its rank-and-file standing alongside Christ’s apostles.

2022

I’ve been thinking about how I would go about interpreting the Crater battlefield and Blandford Cemetery today in light of the past few years. For me Civil War battlefields have never been solely about the war itself. The history of the battles are one chapter in a much longer story.

Like many of you, I am still processing the dramatic transformations that we have witnessed to our Civil War monument landscape. How should our national conversation about race shape a tour of a site like the Crater? What do battlefields mean in the wake of a president who all but embraced Confederate leaders as American heroes? Can we just ignore the fact that right-wing/white nationalists have gathered at places like the Gettysburg battlefield in support of their racist ideology?

Finally, what responsibilities do we have as public historians/educators to address these issues on a battlefield like the Crater in light of the steps that numerous states have taken to censor the teaching of American history?

I can’t think of a more opportune moment to tour and learn from our Civil War battlefields. I look forward to returning to my spot in Petersburg one day soon.

Black soldiers were also the victims of violence perpetrated by their white comrades during the battle. I explore this in a chapter in the book, Cold Harbor to the Crater: The End of the Overland Campaign edited by Gary W. Gallagher and Caroline E. Janney (UNC Press).