On this day in 1863 the Confederate Congress passed a resolution signed by President Jefferson Davis declaring that, “negroes or mulattoes, slave or free, taken in arms should be turned over to the authorities in the state in which they were captured and that their officers would be tried by Confederate military tribunals for inciting insurrection and be subject, at the discretion of the court and the president, to the death penalty.”

The resolution, coming just months after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln, clarified for Confederates just what was at stake in the war—nothing less than the end of an economy and social system based on chattel slavery.

The secession of Southern states and the eventual formation of the Confederacy was an attempt to maintain racial control in the face of a perceived threat in the election of Lincoln and the ascendancy of the Republican Party. The assumption was that slavery was safer outside the United States than within it. By 1863 this assumption was being challenged on multiple fronts.

Enslaved people found ways to undermine the Confederate war effort by running away and undermining operations on plantations and farms across the South through more subtle methods. The movement of the army also proved to be a powerful magnet for enslaved people who viewed it as an army of liberation even before 1863.

It was the United States army that undermined any belief that enslaved people would remain loyal to the their masters and the Confederacy. The enlistment of Black men forced Southerners to confront their worst fears about slave rebellions stretching back decades to Nat Turner as well as numerous uprisings in the Caribbean.

The proclamation that was issued by Davis and the Confederate Congress should be understood as an organic response to the evolution of the war by 1863. Confederates —regardless of whether they were slaveowners or nonslaveowners—didn’t need a proclamation to know how to respond to armed Black men on the battlefield.

They would treat such men in the only way they knew how: as slaves in rebellion.

Black men were slaughtered on battlefields throughout the remainder of the war, including most notably at Fort Pillow in April 1864 and at the Crater, just a few months later, in July. As I showed in my first book on the battle of the Crater, Confederates relished in retelling the stories of how they executed Black men after they had surrendered. They wanted their loved ones back home to understand what was at stake with the introduction of armed Black men.

This particular proclamation helps us to better understand why the war lasted as long as it did. There was no going back for the Confederacy. Defeat now meant the end of slavery and perhaps even racial control.

Finally, this proclamation also helps us to understand why Confederates waited so long to consider arming Black men themselves and why the decision to do so came only weeks before the Confederacy’s collapse in the spring of 1865.

Anyone who believes that the Confederacy armed Black men before March 1865 must first come to terms with this proclamation.

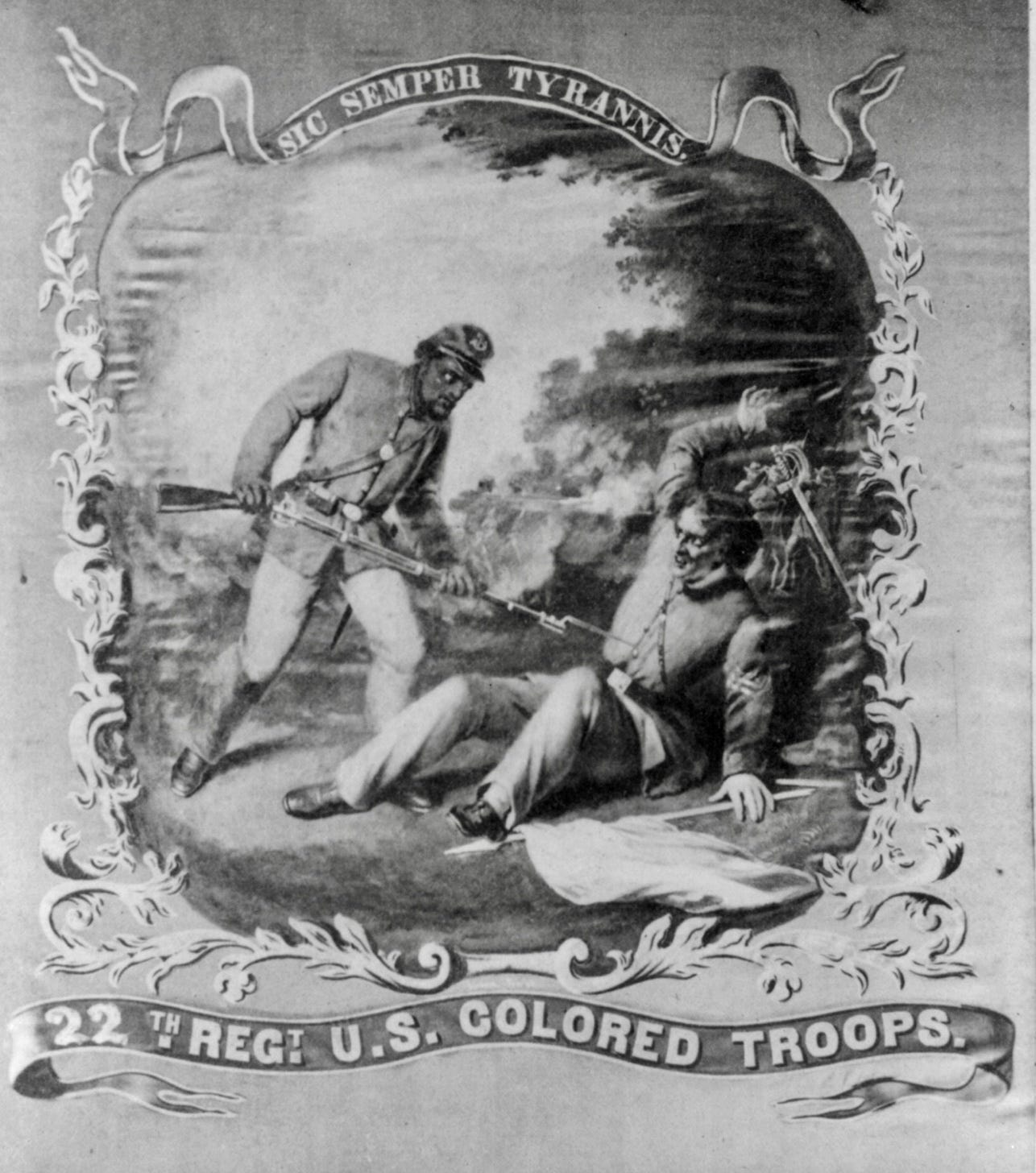

By the end of the war roughly 200,000 African Americans chose to disregard this proclamation and helped to bring about the defeat of a slaveholding republic in hopes of finding a new place at the table in a reunited nation.

There's "Sic Semper Tyrannis" as expected. It was the "Don't Tread On Me" reactionary appropriation of its day.