Last week President Joe Biden delivered a campaign speech at the Mother Emmanuel AME church in Charleston, South Carolina. The speech was loaded with references to the history and legacy of the Civil War and slavery. President Biden even referenced the Lost Cause narrative.

Look, after the Civil War, the defeated Confederates couldn’t accept the verdict of the war: They had lost. So, they say — they embraced what’s known as the Lost Cause, a self-serving lie that the Civil War was not about slavery but about states’ rights. And they’ve called that the noble cause.

That was a lie, a lie that had — not just a lie but it had terrible consequences. It brought on Jim Crow….

Now — now we’re living in an era of a second lost cause. Once again, there are some in this country trying — trying to turn a loss into a lie — a lie, which if allowed to live, will once again bring terrible damage to this country. This time, the lie is about the 2020 election, the election which you made your voices heard and your power known.

As far as I am aware, this is the first time that a sitting president has referenced the Lost Cause in a speech. A number of commentators and historians have attempted to compare Donald Trump’s “Big Lie” about the election of 2020 with the Lost Cause. These comparisons began in the months leading to election night, as Trump attempted to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the vote in the event of his defeat, and especially in the wake of the January 6 insurrection.

It’s not difficult to appreciate why this comparison has proven so popular. Supporters of Donald Trump have embraced symbols of the Confederacy, including the battle flag at campaign rallies and other events. Trump himself has praised Confederate leaders on more than one occasion, most notably following the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville in August 2017.

And certainly no one will forget the sight of Kevin Seefried walking through the U.S. Capitol Building on January 6, 2021 with a Confederate flag.

Trump’s own racist statements over the years make it easy for many to tie him to the Confederate past.

That said, I’ve never been comfortable with comparisons between the Big Lie and the Lost Cause.

A big part of my concern is with characterizing the Lost Cause as a lie. Before proceeding let me be clear that white southerners did indeed reframe much of the narrative about the Civil War in the years after defeat, especially when it came to the cause of the war. In 1861, white southerners were clear about slavery’s importance, but after the war shifted to an explanation that cast secession as a defense of the Constitution and states’ rights.

But casting the Lost Cause framework as a lie reduces it to a point where it is simply impossible to appreciate the difficulty and challenges that many white southerners faced trying to move on in the wake of defeat, death, and emancipation. Casting the South as unified; its generals as Christian warriors; and defeat as inevitable helped to make sense of the drastic changes that befell the population.

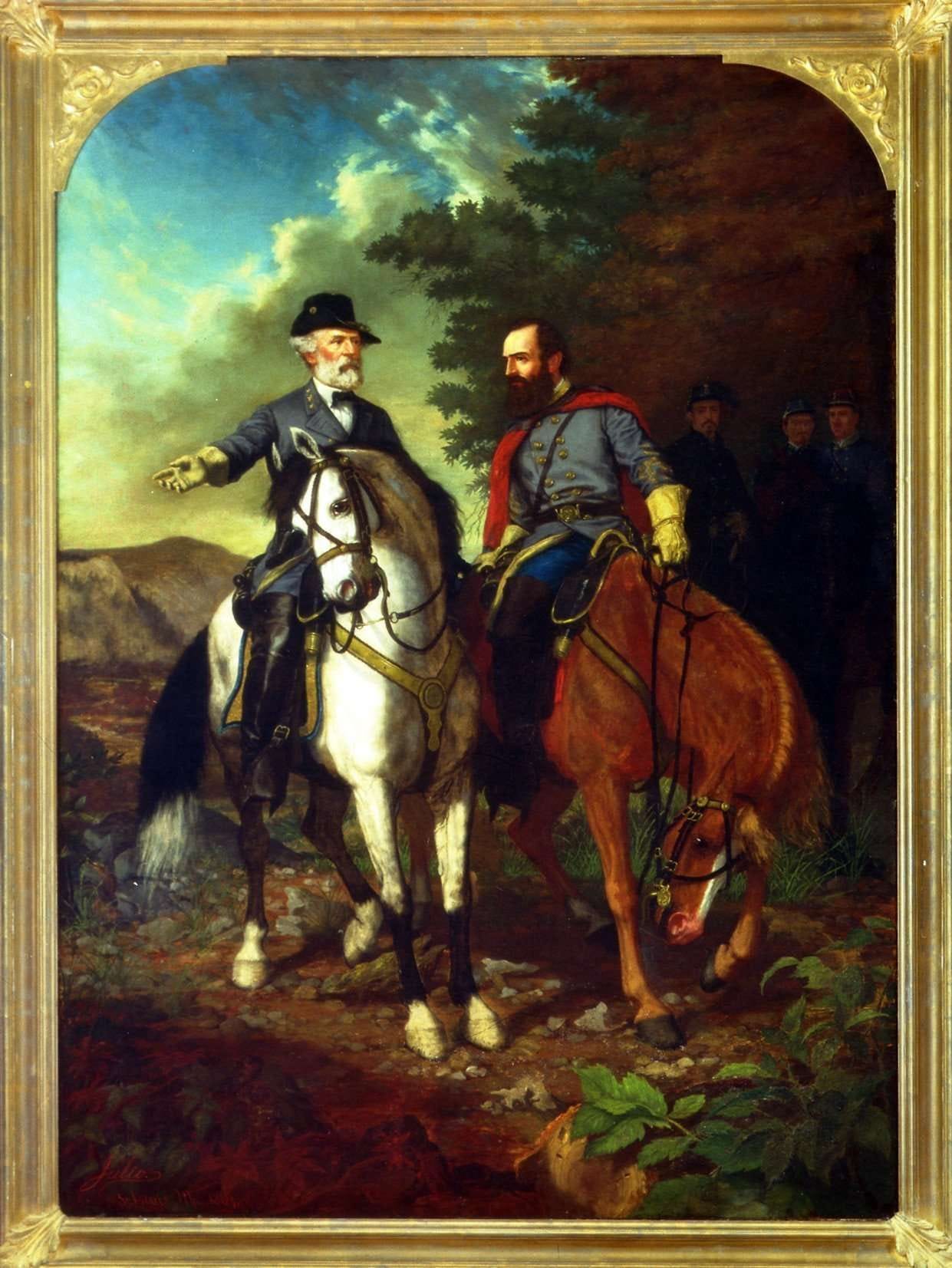

There were echoes of truth in many Lost Cause strands. Certainly, United States military might helped to overpower Confederates. According to a number of historians, Confederate nationalism remained strong throughout much of the war. Many Confederate generals, including “Stonewall” Jackson were known and celebrated for their strong Christian faith.

Other threads of the Lost Cause narrative did not need any revision. White southerners from the slaveholding class had long maintained that African Americans benefitted from enslavement and that race relations were peaceful throughout the antebellum South.

Describing the Lost Cause as a lie also fails to appreciate the ways in which it evolved over the course of decades and how it was manipulated or leveraged to serve specific causes, from mourning the dead in the immediate postwar period to justifying legalized segregation during the Jim Crow era.

White Americans outside the South embraced certain aspects of the Lost Cause for various reasons as well. Start with Charles Francis Adams’s speech commemorating the centennial of Robert E. Lee’s birth in 1907

It is also important to remember that there was no ringleader, no Donald Trump-type figure pushing the Lost Cause. It grew organically taking different forms, at different times, in different places, and for a wide range of reasons.

Historian David Blight makes this point in his most recent op-ed in the Los Angeles Times:

Unlike the Confederate Lost Cause, the Trump version is a kind of gangster cult, full of rituals of loyalty to a single man and his plans to fashion an authoritarian U.S. government that will use executive power to achieve his followers’ preferences.

This is an important distinction that should serve as a warning that such a comparison is problematic.

My point is that describing the Lost Cause as a lie tells us very little about how and why so many people have continued to find meaning in it.

“Lost causes can turn lies into common coin and forge deep and lasting myths,” writes Blight. “We are a long way from knowing how much staying power the Trumpian ‘lost cause’ will have, regardless of whether he survives his criminal charges and the election campaign. What we do know is that we have already witnessed its formative years.”

Have we? I think it is still too early to tell. The Lost Cause narrative didn’t just appear fully formed one day in the spring of 1865 or even in 1870. It took years for it to mature into a coherent ideology.

A Better Comparison

Rather than compare Trump’s Big Lie and everything attached to it with the Lost Cause, perhaps a better comparison can be made with Senator Joseph McCarthy and the brief rise of McCarthyism.

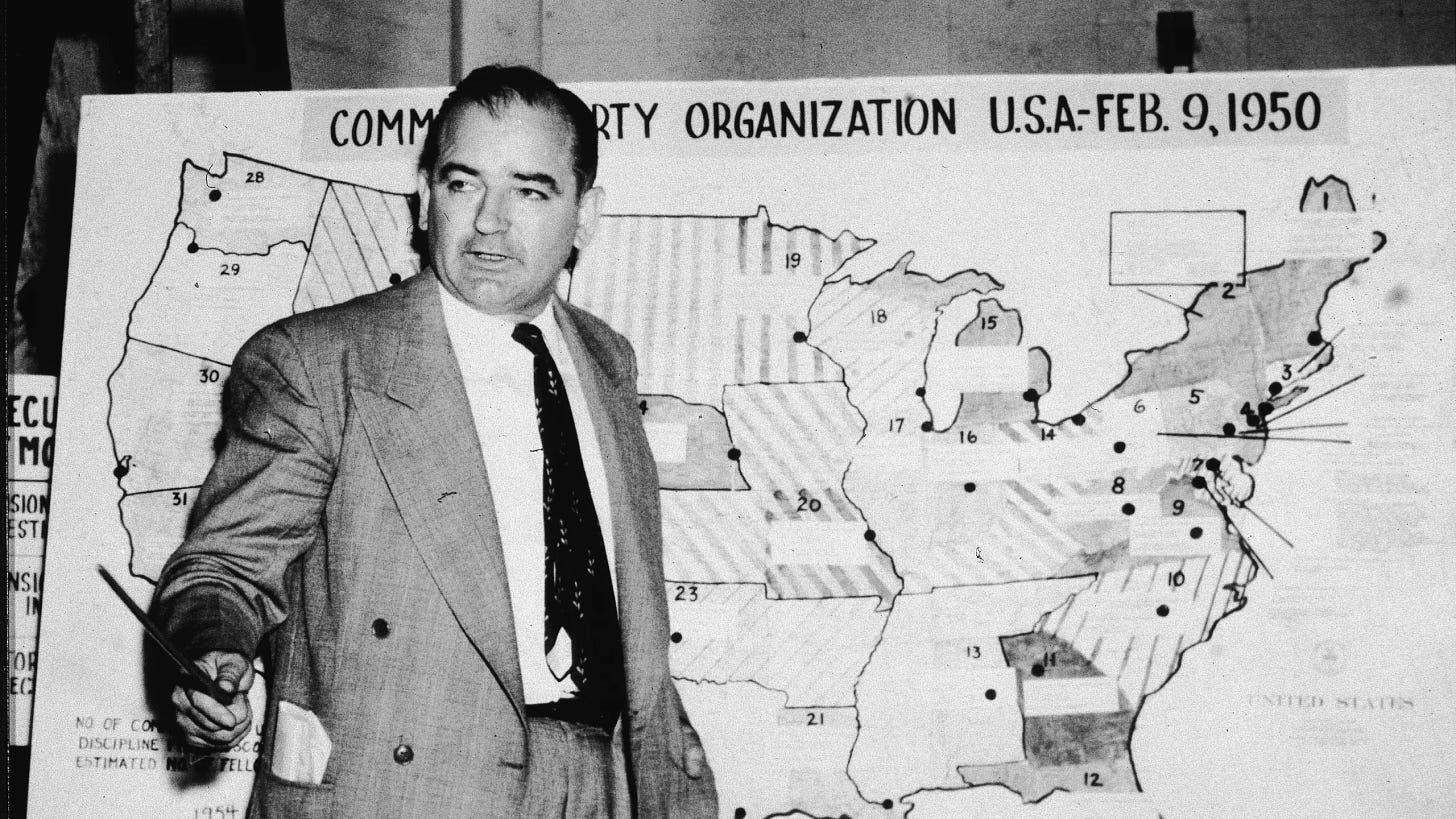

In February 1950, Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin delivered a speech in Wheeling, West Virginmia in which he claimed that 205 employees in the State Department were members of the Communist Party.

Here is how historian James T. Patterson interprets McCarthy and his crusade in Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974:

These were sensational charges. McCarthy, after all, was a United States senator, and he claimed to have hard evidence. Intrigued, reporters asked for more information. Doubters denounced him and demanded to see the list. McCarthy brushed them off and never produced one. His information, indeed was at best unreliable, probably based on FBI investigations of State Department employees, most of whom were no longer in the government. In subsequent speeches—he was on a ‘Lincoln Birthday’ tour—McCarthy changed the figure from 205 to fifty-seven. When he spoke on the subject in the Senate on February 20, he rambled for six hours and bragged that he had broken ‘Truman’s iron curtain of secrecy.’ The numbers changed again—to eight-one ‘loyalty risks’ in the State Department—but McCarthy remained aggressively confident. ‘McCarthyism’ was on its way. (p. 196)

Everything about this screams Trump, especially his handling of the media, contradictory and inconsistent statements, and especially his defiance in the face of questioning.

He kept up the hammering, rarely relenting for long, for more than four years. He was remarkably inventive and imaginative in doing so. As before he did not worry about lying. Again and again he would stand up, pulling a bunch of documents from his briefcase, and improvise while he went along. As his audiences grew, he became more and more animated and skillful at spinning stories. When opponents demanded to see documents, he refused on the ground that they were secret. When caught in an outright lie, he attacked his accuser or moved on to others lines of investigation. Few politicians have been more adept in their use of rhetoric that makes good headlines. Repeatedly he blasted ‘left-wing bleeding hearts,’ ‘egg-sucking phony liberals,’ and ‘communists and queers.’ (p. 199)

It’s as if Trump copied McCarthy’s playbook for how to try to hoodwink a nation.

Patterson also emphasizes McCarthy’s ability to appeal to “people who nursed hostility toward elites, especially in government” and take advantage of racial, class, ethnic, and religious tensions in the uncertainty of the postwar period and in response to the perceived Soviet threat.

Of course, we know how this story ended. While it is unlikely that Trump will experience a “Have You No Shame” moment, it is still very much a question as to whether the Big Lie will survive Trump. I have my doubts.

It seems to me that it is much more helpful to view Trump and the Big Lie alongside other demagogues throughout American history and beyond. McCarthy is just one example. There are important lessons to be learned from our history that can help steer this nation through this current crisis.

The Civil War and its legacy looms large in our current public discourse, as it should, but there are other moments in our history that may also offer insights, warnings, and direction.

Thanks for reading.

Isn't the term, "Big Lie," derived from a whole different historical precedent (something about Goebbels, right)?

I don't take much stock in how politicians and op-ed writers use the past, but I know there are historians who like this comparison. Haven't paid close enough attention, but why do they find it compelling?