Thanks to the good folks over at Shepherd for giving me the opportunity to share some of my favorite Civil War books. You’ve no doubt seen these lists floating around in various subject areas. I’ve picked up a few titles over the past few months as a result.

I decided to group my picks around the broad subject of slavery and the Confederacy, though I was specifically interested in books that focus on the Confederate military and which helped me with researching and writing Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth.

You can read why I selected my top 5 books at Shepherd, but I thought I would offer a few more suggestions below for those of you who are interested in reading further.

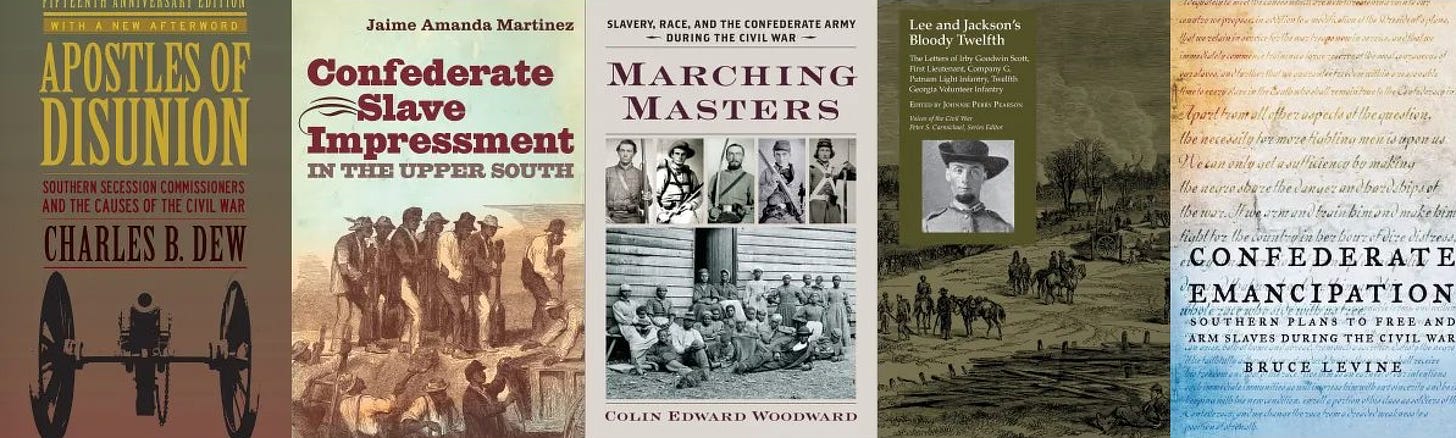

(Overview): Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War, by Charles B. Dew

Anne Sarah Rubin’s A Shattered Nation: The Rise & Fall of the Confederacy: 1861-1868 offers a nice overview of how slavery fit into expressions of Confederate nationalism during the war and how it was transformed as part of the Lost Cause narrative in the years and decades to follow. Similarly, Michael Bernath’s book Confederate Minds: The Struggle for Intellectual Independence in the Civil War South offers a cultural analysis of the antebellum and wartime defense of slavery by analyzing how it was understood in, among other settings, intellectual circles, in religious sermons, the theater, and southern textbooks.

(Military Mobilization of Slaves): Confederate Slave Impressment in the Upper South, by Jaime Amanda Martinez

Though it’s a bit dated (1969), James H. Brewer’s book The Confederate Negro: Virginia’s Craftsmen and Military Laborers, 1861-1865 offers a thorough overview of how enslaved labor was utilized for military purposes in Virginia. Someone really needs to write an updated version of this study. For a thorough debunking of the continued misinterpretation of newspaper accounts from the spring and summer of 1862, purporting to demonstrate the existence of Black Confederate soldiers, see Glenn D. Brasher’s wonderful book, The Peninsula Campaign & the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom. Yes, they were body servants and impressed slaves, but Brasher shows how these newspaper reports spurred Lincoln and the Republicans to move more quickly toward emancipation.

(Confederate Soldiers and Slavery): Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army During the Civil War, by Colin Edward Woodward

For a thorough overview of changing attitudes of Confederate soldiers toward slavery, see Chandra Manning’s book, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War. On slavery and the Army of Northern Virginia, check out Joseph Glattthaar’s book, General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse. You may also want to pick up the companion volume, which includes graphs and charts that break down the structure and profile of Lee’s army. Finally, though it’s also a bit dated (1938) and difficult to find, Bell I. Wiley’s Southern Negroes: 1861-1865 explores the presence of body servants in the army and has some interesting things to say about the relationship between enslaved men and Confederate officers.

(Published Primary Sources): Lee and Jackson's Bloody Twelfth: The Letters of Irby Goodwin Scott, First Lieutenant, Company G, Putnam Light Infantry, Twelfth Georgia Volunteer Infantry, by Johnnie Perry Pearson

I do love reading published diaries and letter collections from Civil War soldiers. Here are two additional titles, whose authors go deep into their relationship with their camp slaves and a whole host of other issues. They are, A Gunner in Lee’s Army: The Civil War Letters of Thomas Henry Carter, edited by Graham T. Dozier and One of Lee’s Best Men: The Civil War Letters of General William Dorsey Pender, edited by William W. Hassler.

(Slave Enlistment Debate): Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War, by Bruce Levine

Robert Durden’s book, The Gray and the Black: The Confederate Debate on Emancipation offers a thorough overview of the enlistment debate, but also includes excerpts from a wide range of newspapers from different parts of the Confederacy. More recently, Philip D. Dillard addresses the enlistment debate in Jefferson Davis’s Final Campaign: Confederate Nationalism and the Fight to Arm Slaves and concludes that the position taken by different communities depended, in large part, on whether they were far removed from the fighting or in close proximity.

I hope these suggestions help. Feel free to share other titles that fall into these categories.

In about 1970, while in grad school at Emory University, I took Bell Wiley's legendary course on the Civil War and enjoyed it thoroughly. Well, OK, maybe not thoroughly. You see, the course was open to both undergraduate and graduate students. Dr. Wiley was in the habit of seating his grad student attendees together in the front row and peppering us (but not the undergrads) with questions I considered "trivia," though he clearly did not. And, honestly, it kept me on my toes, although I can't speak for my fellow grad students. Oh, and we did not get past the Battle of Gettysburg in the first two quarters of the course (the third quarter was given over to "independent research").

Dr. Wiley required us to read at least one book a week (though after a couple of my reviews on a single book, he wrote me a note urging me to "read more!," so of course I did. Among the volumes I read was his book The Southern Negro and even submitted a review of it. Dr. Wiley had said at the start of the course that anyone who read his book and reviewed it would probably get an "A" on the review, even though he didn't he really didn't want to read them! So I did! And got an "A"!

Oh, and a year or so later, when I was trying to get approval for a dissertation topic in Georgia history (post-Revolution through the early nineteenth century), I approached Dr. Wiley about being on my committee. He readily agreed, but he also warned me that agreement didn't necessarily mean he'd spend a lot of time reading my dissertation. Again, I said, "Yes, bwana" and motored on into the joys of dissertation research. I think Dr. Wiley relented about reading (or at least skimming) my dissertation--he knew my work from his Civil War course and trusted that I would do work of equal caliber in the dissertation. And, as I was wrapping things up several years later (the degree came in 1973), he had kind things to say about it.

Moreover, the old fox invited all of the members of his Civil War class to lunch at his home. But--wait for it!--the Good Doctor had neglected to tell his wife that he'd done so. Still, Ms. Wiley was obviously used to this, recovered nicely, and a good time was had by all. (I have a feeling that Dr. Wiley might have had to help with the dishes afterwards, though I can't swear to it!)

Anyway, thanks for mentioning his 1938 book in your historiographical essay about "Slavery and the Confederacy." That single reference brought all sorts of recollections of Dr. Wiley bubbling up to the surface of my brain (what's left of it!)--and led me to send this email.

Thanks,

George Lamplugh, Ph.D. (Emory, 1973); The Westminster Schools, Atlanta, Ga. (1974-2010); and author of his own blog, "Retired But Not Shy": https://georgelamplugh.com/2022/04/02/reflections-on-race-part-2-teaching-civil-rights-15/