Teaching the Confederate Monuments Controversy

I was pleased to see this lesson plan on the Confederate monument controversy today in The New York Times. It does a great job of framing the current debate within the context of the police murder of George Floyd and other incidents on the racial front. Since June 2020 roughly 110 Confederate monuments and statues have been removed across the country.

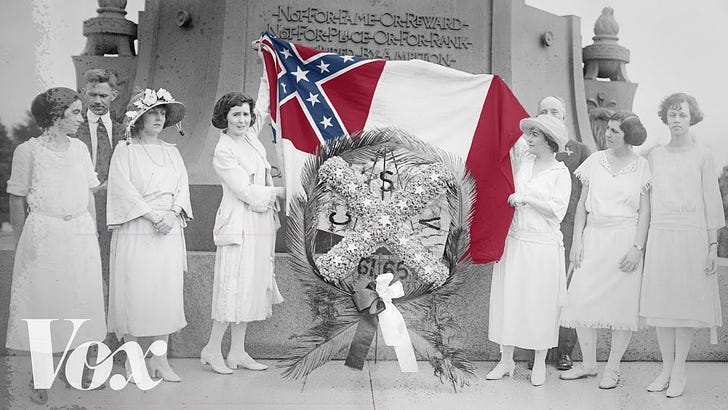

In this lesson plan, students are asked to respond to a series of photographs and information about where monuments currently exist, where they have been removed, and whether vandalism or “tagging” is ever justified.

I particularly appreciated having students survey their local monument landscape in order to get a better sense of who is honored and whose stories are commemorated. This allows students to better appreciate the stories that are missing from public spaces and whether or how this should be addressed. In addition, having students work together to design their own monument givea them some sense of the difficulty of deciding who or what to remember, what form it will take, and why the choice is justified.

With few exceptions, the public conversations that have taken place in local communities has left students on the sidelines. This is unfortunate given the fact that students today are exposed to a much richer and more inclusive historical narrative compared with their parents and grandparents. It is entirely reasonable for students to inquire and debate whether the current monument landscape reflects individuals and events that are deemed worthy of commemoration.

My only complaint is that this lesson plan fails to offer any historical framework for understanding the monuments themselves. This commemorative landscape didn’t just appear out of nowhere and the controversy surrounding their presence, in many cases, extends back to the very day these monuments were dedicated. Understanding this complex history is important in evaluating whether they should remain or be removed/relocated.

Here is a short video that can provide some context for students.

Teachers might also share a couple dedication addresses with students to better understand how white southerners interpreted these monuments during the Jim Crow era.

Here is arguably one of the most controversial addresses, delivered by Julian Carr in 1913:

The present generation, I am persuaded, scarcely takes note of what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo Saxon race during the four years immediately succeeding the war, when the facts are, that their courage and steadfastness saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South – When “the bottom rail was on top” all over the Southern states, and to-day, as a consequence the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern States – Praise God.

I trust I may be pardoned for one allusion, howbeit it is rather personal. One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.

Wiley Nash’s address in 1908 is also very helpful.

Engaging students to think critically about monuments is a wonderful way to remind them of the ways in which history and memory surround us. How we have chosen to remember and commemorate our collective past has often divided us, but it can also bring us closer together around a shared set of values.