Everyone is up in arms about the new state standards for the teaching of African American history that were approved this week in Florida. Seriously, what did you expect from a DeSantis administration right now? I have not had a chance to read the report in its entirety for myself, but I don’t doubt that it is problematic.

But that is the nature of this process. It’s political. That doesn’t mean that every attempt to craft new standards will end in complete disaster. There is evidence to suggest that the history standards recently passed in Virginia have some merit, but all of this overlooks one key fact.

This is a political process. It’s using the “study” of history to shape a certain way of thinking about the country that will hopefully translate into a certain kind of voter. Of course, it’s never explicitly stated, but that is the assumption that goes into the question and process of trying to decide what students should learn about the past and why. Democratic administrations appoint committee members who share a certain world view and Republicans do as well.

State history standards treat students merely as sponges whose job it is to absorb information rather than emphasizing how to think critically about the past. In other words, think like a historian.

Our focus shouldn’t be on what students ought to learn and regurgitate, but on professional development for teachers. We should be training our teachers in how to engage students in the process of thinking about and doing history at different grade levels.

The very idea of state history standards hearkens back to a time before the Internet when the primary vehicle of history education was the textbook and a school library of printed materials, including books and magazines that students would use to write reports and essays.

Today it makes little sense to try to standardize content given the amount of information that students can now access. We should be giving them the tools to sift through and evaluate digital sources.

Criticizing the DeSantis administration for using history to advance a blatantly political agenda, given his presidential ambitions, is perfectly justified, but it misses the bigger problem with the process itself.

As frustrating as it is, I like to remind people that these blatant attempts to censor the teaching of history for political purposes rarely succeed in the long term. In fact, the attempt to control what students learn through state standards is itself evidence that their architects are, once again, on the defensive.

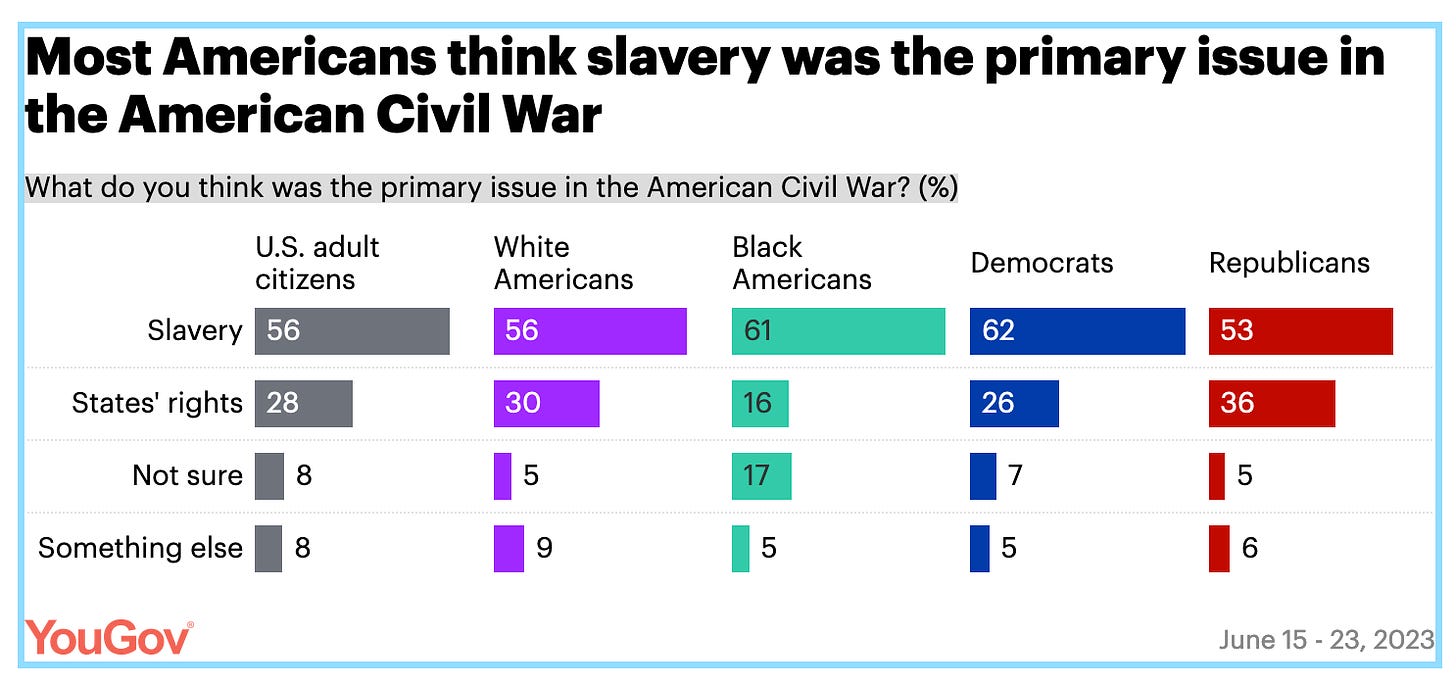

On the other hand, a new poll offers some interesting insights into how Americans think about the Civil War. This latest one from YouGov confirms a number of previous polls, especially in reference to the increasing acknowledgment that slavery was central to the war.

As I’ve said before, this is a significant shift in our collective thinking compared to just a few decades ago.

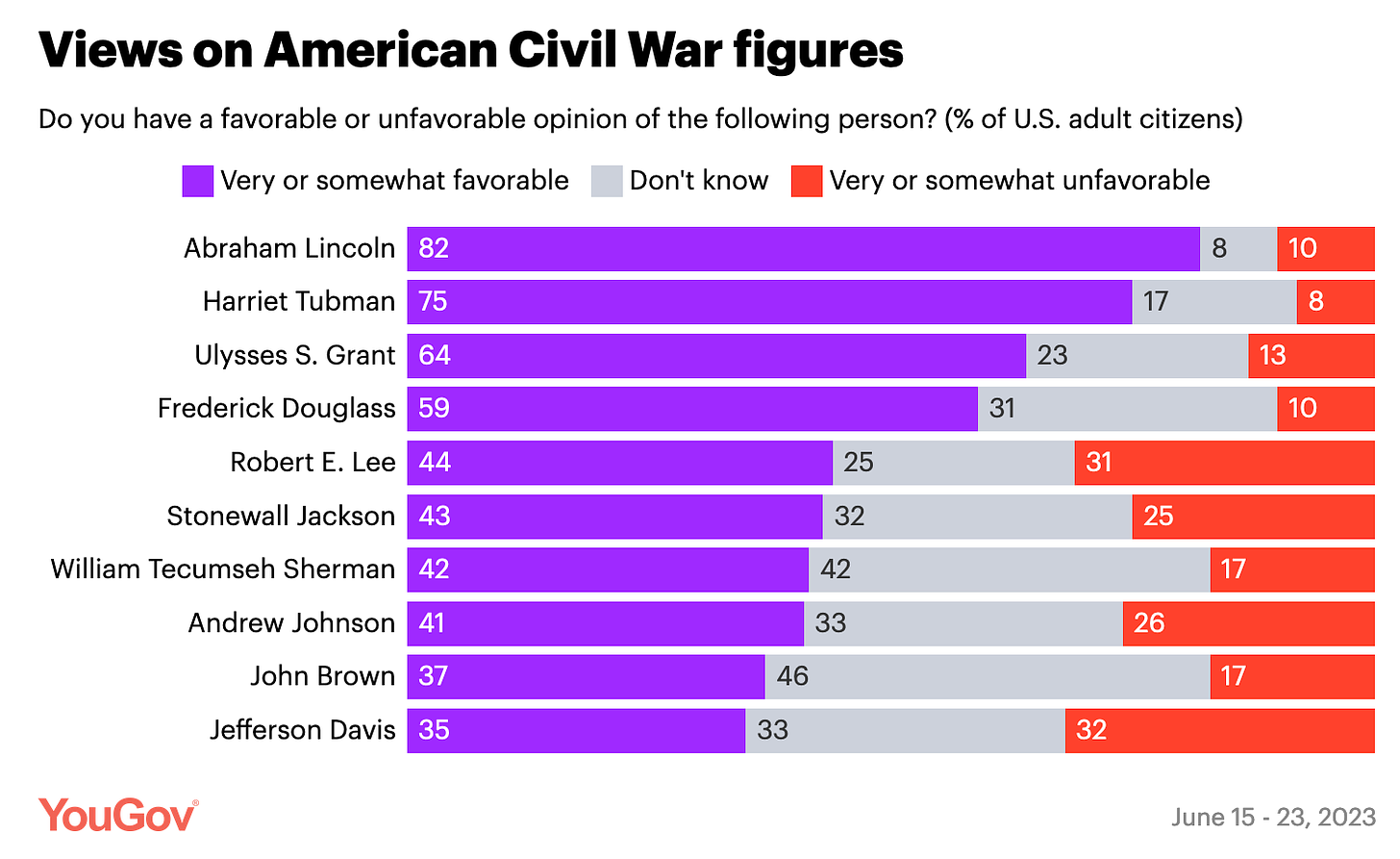

If you are looking for evidence of a waning influence on the part of the Lost Cause narrative, notice that Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson both fall below Lincoln, Tubman, and even Ulysses S. Grant. Grant’s rise is certainly the result of the increased attention he has received through a wave of new books and documentaries.

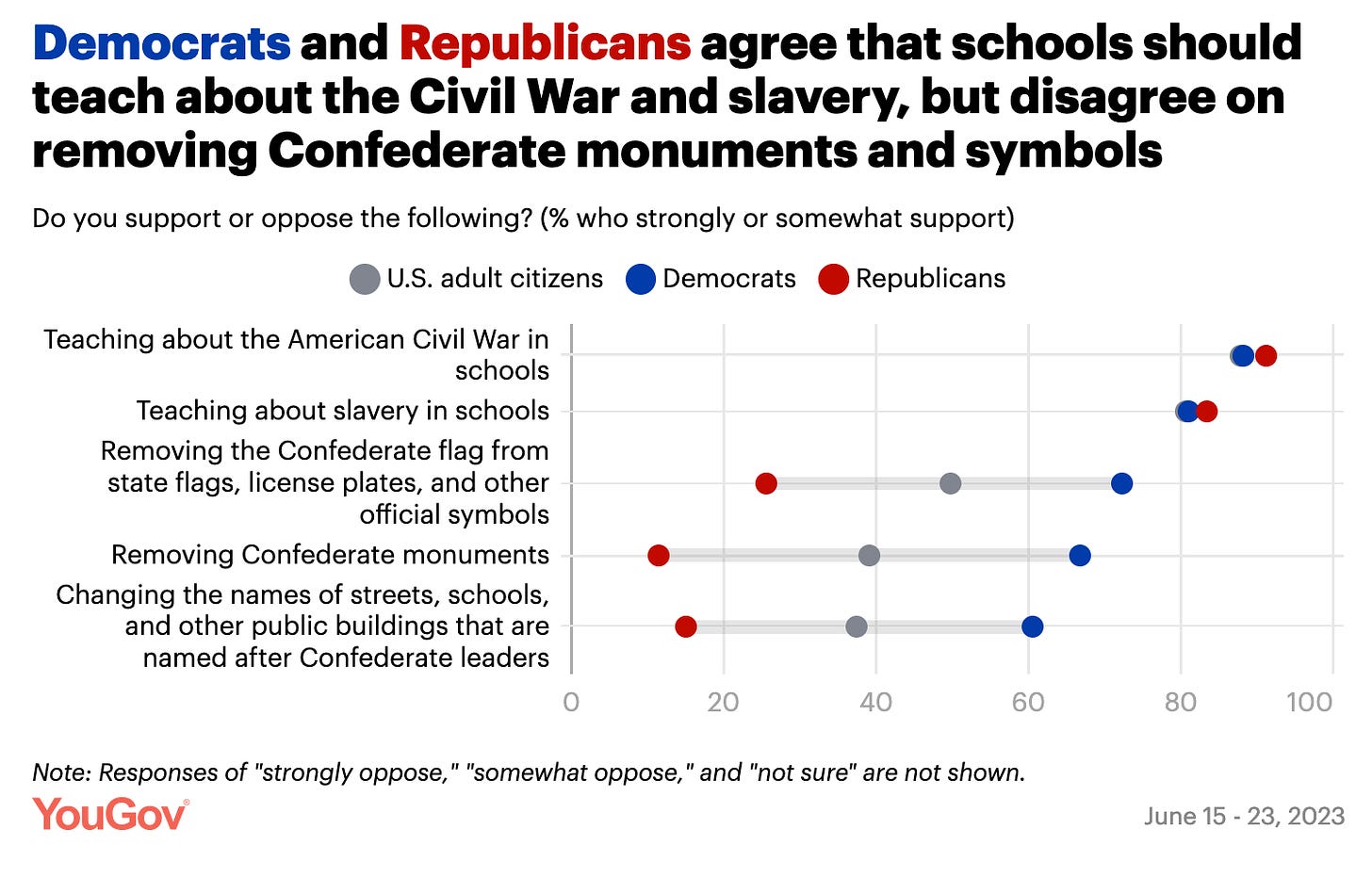

No surprise to see that the politics of Civil War memory is illustrated most clearly in connection to questions about the ongoing debate about Confederates symbols like the battle flag and monuments.

I have not had a chance to read the full report, but again these results reaffirm similar polls in recent years.