I first met Myra Chandler Sampson online back in 2010. At the time she was working tirelessly defending the history of her famous great grandfather. Silas was what you might have called the poster boy for the Black Confederate myth.

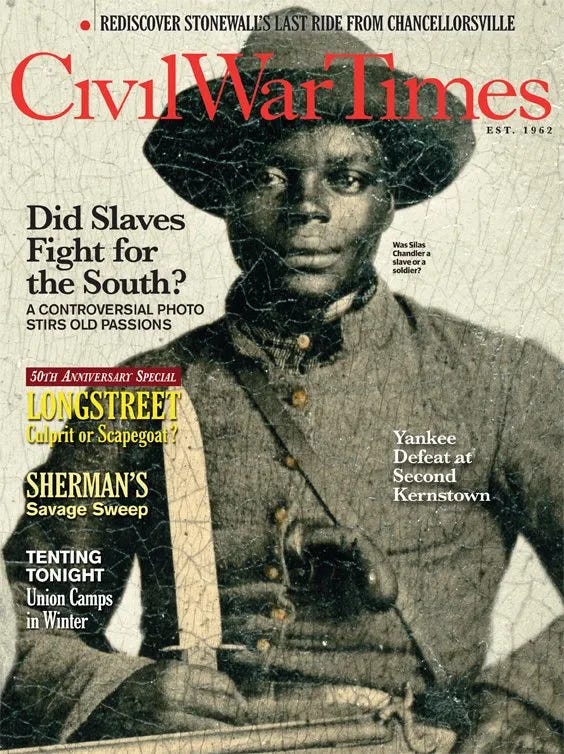

The photograph of Silas and Andrew Chandler, both wearing Confederate uniforms and brandishing numerous weapons, could be found on hundreds of websites purporting to demonstrate the existence of large numbers of Black Confederate soldiers, who served bravely alongside their white comrades in integrated regiments.

I had only recently discovered the subject, but by 2010 it had become the most popular and divisive subject on my blog.

Myra regularly traveled to her ancestor’s grave in West Point, Mississippi to remove Confederate flags and the Southern Cross of Honor, a commemorative medal awarded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to honor Confederate veterans for their service during the American Civil War.

West Point was where Silas and his wife Lucy were enslaved and it’s where they made a life for themselves after the war for their children, which laid the groundwork for generations of Chandlers to follow. It is a story of achievement in the face of unspeakable challenges, beginning with enslavement and continuing through Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era.

Despite the uniform and weapons, Silas never ‘served’ the Confederacy or fought as a soldier in the Confederate army. Like thousands of other Black men, Silas went to war, attached to his enslaver, as a body servant or what I call camp slave.

The two of us stayed in touch and in 2012 co-authored an article that appeared in the 50th anniversary issue of Civil War Times magazine. The article is one of my proudest achievements as a historian and writer. What a thrill it was to see Silas featured alone on the cover of the magazine.

A few years later the two of us were interviewed for and even slated to appear on an episode of History Detectives devoted to the famous photograph of Andrew and Silas. Unfortunately, we didn’t appear in the episode, but our research and knowledge of the story helped to further debunk the myth.

In 2014, the photograph was sold to the Library of Congress for an undisclosed amount by one of Andrew Chandler’s descendants. Silas is clearly and accurately described on the website as an enslaved body servant.

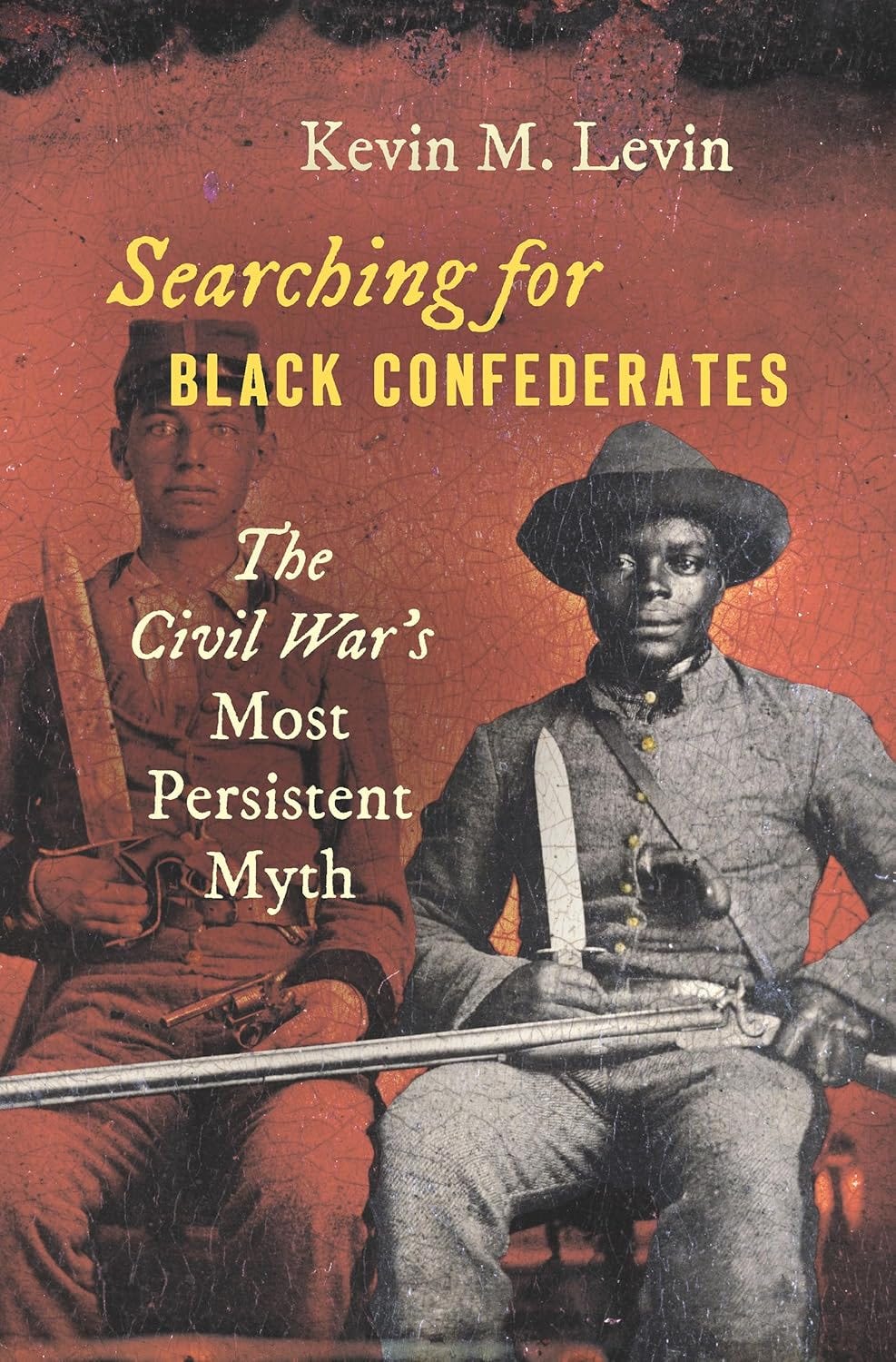

Finally, in 2019 the image of Andrew and Silas was featured on the cover of my book Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. One of my favorite moments from the release of the book was having the opportunity to sign and send a copy to Myra, who, in turn, shared it with the rest of her large family.

I love how the book jacket designer managed to bring Silas out from behind the shadow of his enslaver.

The work that Myra and I did to challenge the Confederate heritage community and that helped to clarify this subject for the general public has made a difference. Sure, you can still find the photograph misinterpreted on websites and social media by some of the same individuals and organizations, but you are just as likely to find a reference to my book or one of the other sources mentioned above.

I hadn’t heard from Myra in quite some time, but just the other day she messaged me with some wonderful news.

In October of last year, the city of West Point held a ceremony dedicating Mayhew Street with a new name that honors Silas Chandler. They just got around to putting the sign up.

I couldn’t be happier for Myra and the rest of her family. Mayhew Street is the street where Myra and her siblings were born and raised. Mt.Herman Baptist Church, which Silas helped to construct after the Civil War is also located on this street.

Notice that the sign does not identify him as a Black Confederate or attempt, in any way, to place Silas within a pro-Confederate narrative.

Silas survived the Confederacy and he managed to survive the Lost Cause as well.

Twenty Years of Blogging

For those of you who are new to my writing here at Civil War Memory it might be appropriate to point out that this year marks twenty years of blogging. I started writing online in early November 2005. Civil War Memory began on Google’s blogspot platform before migrating to TypePad and later WordPress. In 2022 I moved here to Substack.

I mention it because my relationship with Myra, our work together and the countless other opportunities that I have enjoyed as a historian, educator, and writer would not have been possible without my blogging and without dedicated readers like you.

Thank you.

Somehow, "lovely" is the first adjective in my head as I think of Myra and her family devotion.

Myra is noteworthy and it's sad if her identity can't be fully disclosed. I've downloaded the magazine article she and KML wrote. I wonder what she does with the, uh, um, trash, Confederate diehards leave on her ancestor's grave?

Let's take our victories where - where - and however they arrive.

Happy 20th anniversary! And thank you for honestly telling the story of our history.