I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that a new museum opened in 2020 and operated by the Sons of Confederate Veterans in Elm Springs, Tennessee includes exhibits that promote the Black Confederate myth. It will come as no surprise that the exhibit is incredibly misleading, but it is also incredibly predictable and lazy. All of the usual suspects and cliches show up.

As I demonstrated in my book, the Black Confederate myth was originally promoted to counter a burgeoning “emancipationist” narrative of the Civil War in the 1970s. If Black men fought as soldiers in the Confederacy, their advocates argued, then it couldn’t be the case that their ancestors fought to maintain the institution of slavery and white supremacy.

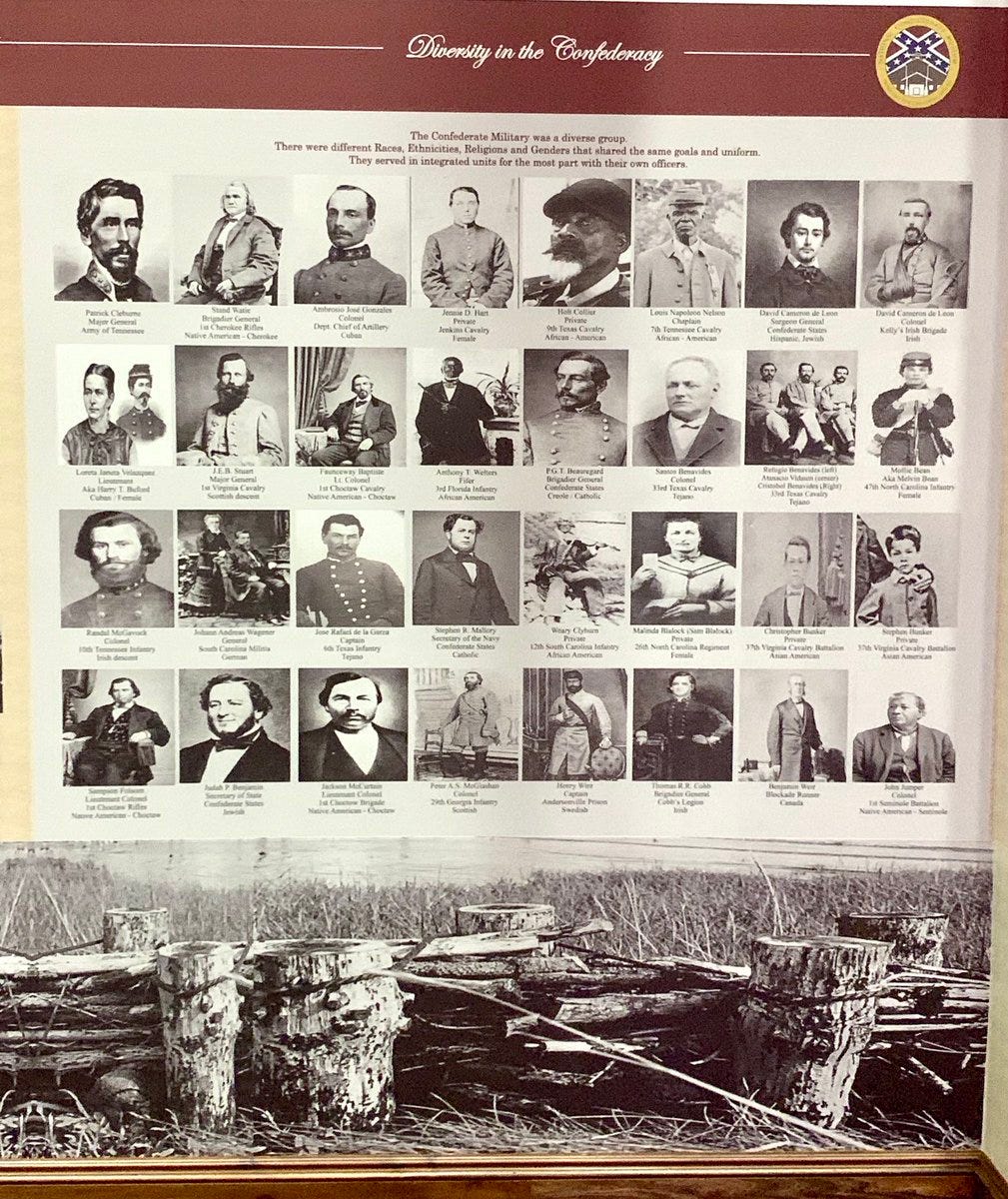

According to the Sons of Confederate Veterans, the “diversity” of the Confederacy shields it from these attacks.

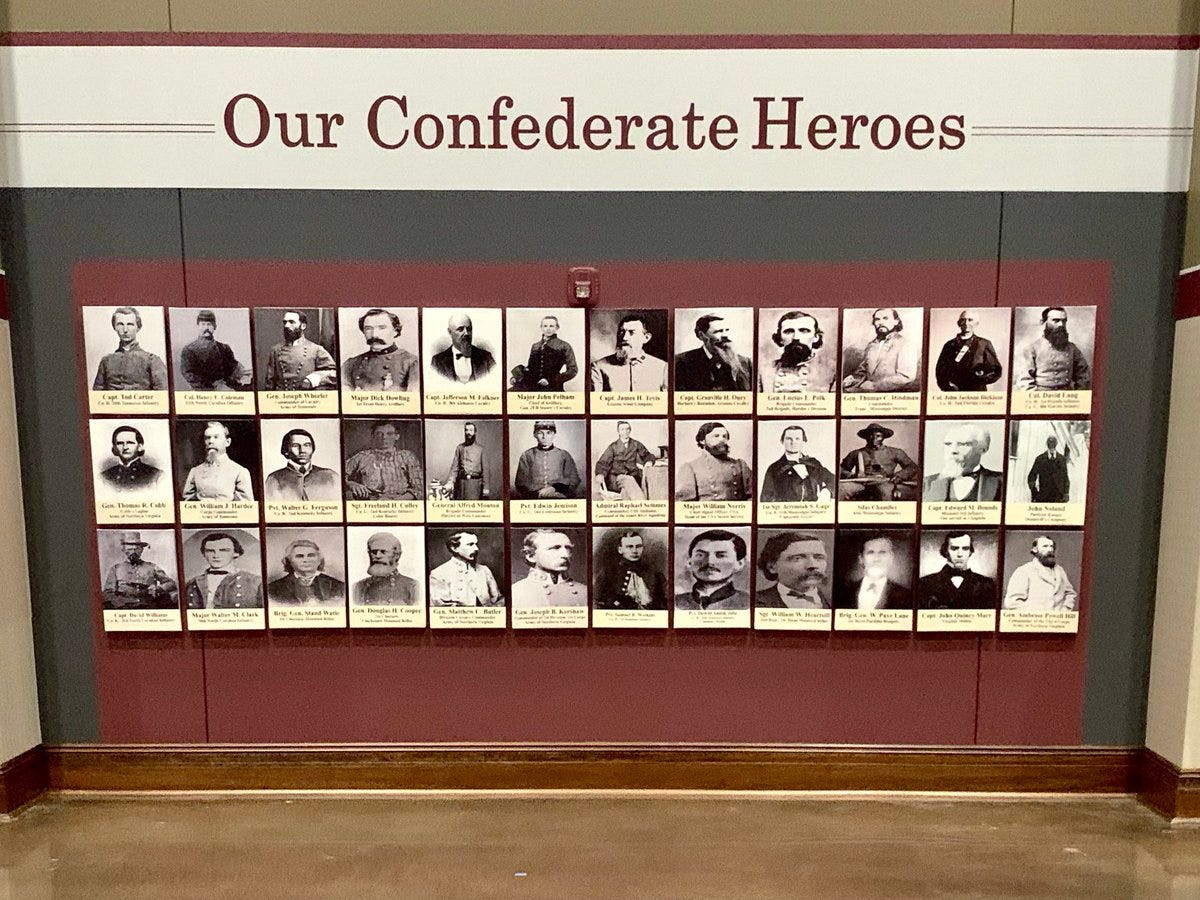

Welcome to the National Confederate Museum.

There is not a single Black individual included in these panels that can remotely be claimed to have fought for the Confederacy. They were all enslaved as body servants or what I call camp slaves.

The museum collapses the distinction between slave and soldier and casts them as a ‘band of brothers’ fighting a common enemy. It is an extension of the Lost Cause belief that enslaved people remained loyal to their masters and the Confederacy right to the end of the war.

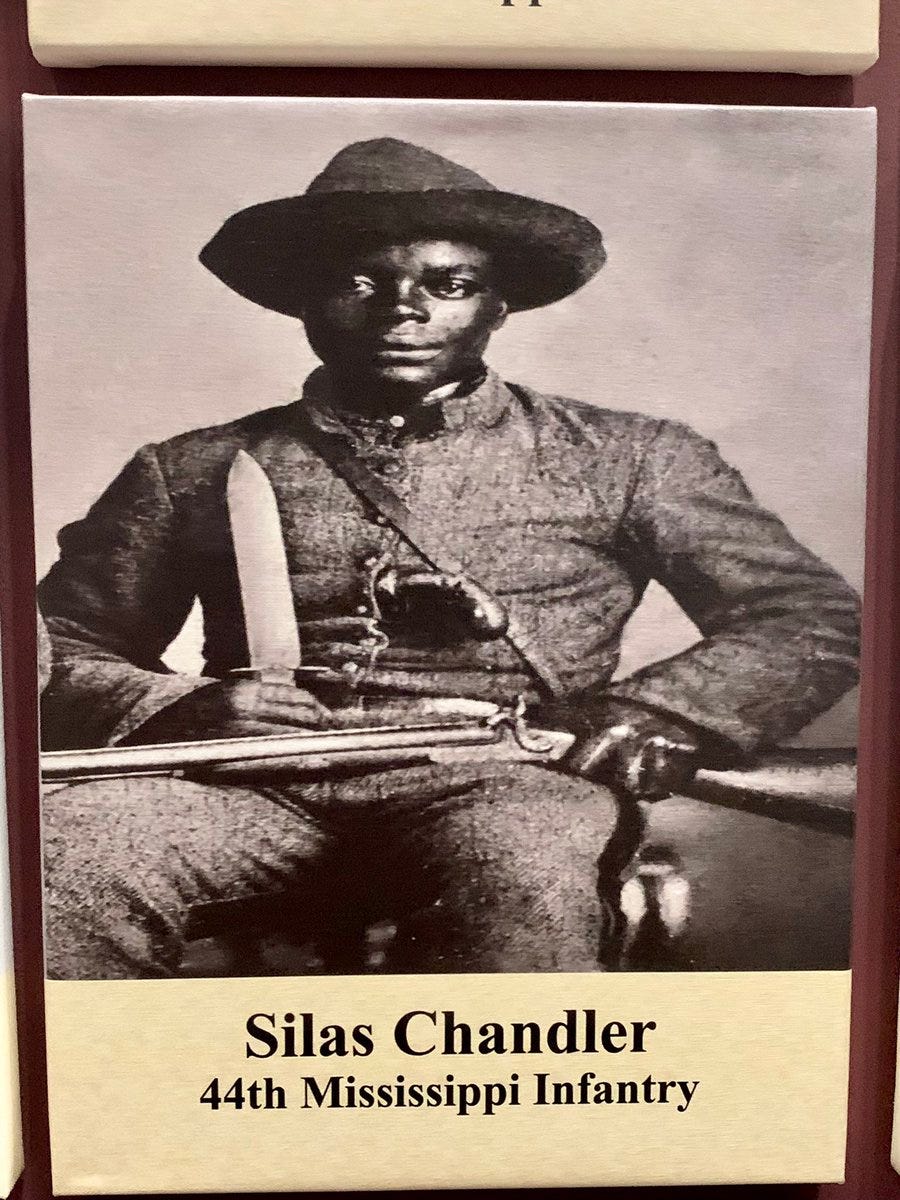

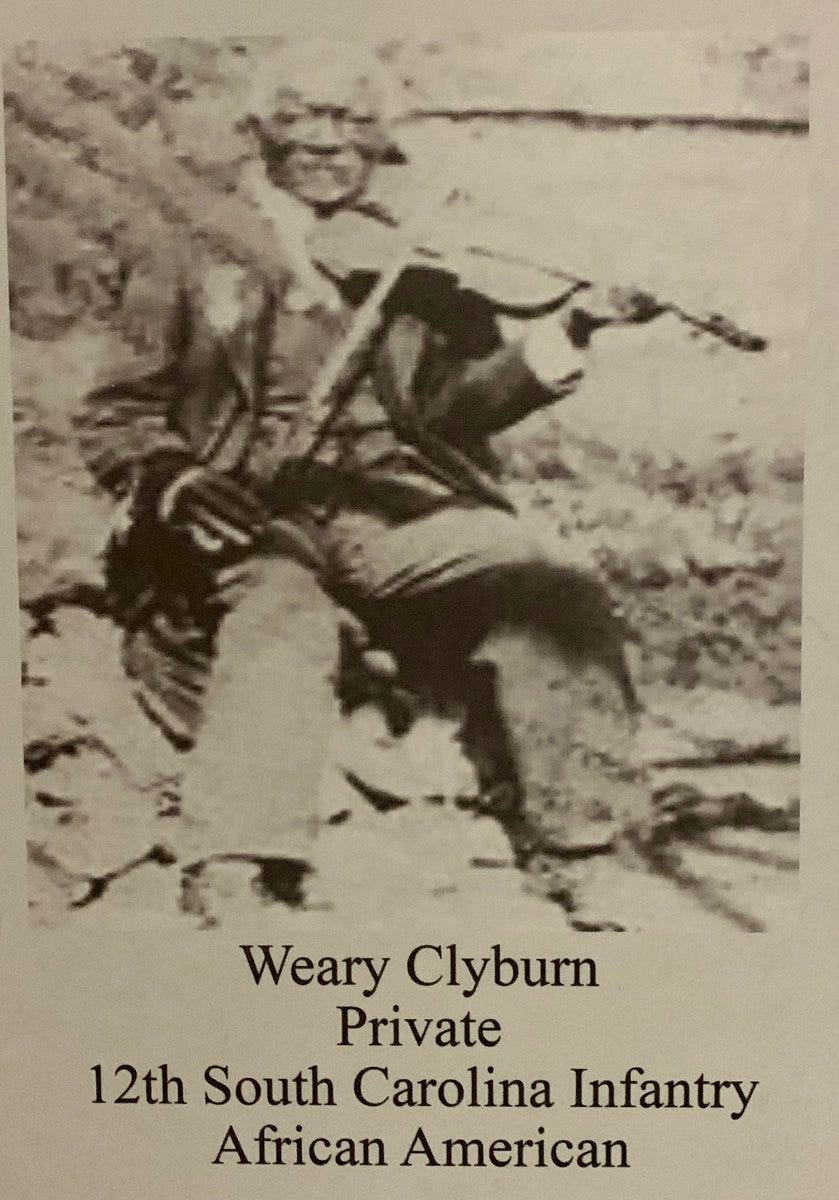

What I find laughable is that they include Silas Chandler and Weary Clyburn.

Most people have given up on trying to cast Chandler as a soldier. The evidence is so overwhelming so as to be irrefutable. Chandler was my entry into this subject. In fact, the first piece I ever published on this subject was co-authored with Silas’s great-great granddaughter for Civil War Times magazine ten years ago.

Silas did not serve as a soldier in the 44th Mississippi Infantry, but the man who owned him did.

The same holds true for Weary Clyburn. I’ve written extensively about Clyburn over the years. The SCV has not only distorted this man’s personal story, but also took advantage of his descendants by purchasing a new military gravestone for Clyburn that included a reference to the 12th South Carolina Infantry. Again, Clyburn didn’t fight as a soldier in that regiment, but the man who owned him did.

In 2014 the SCV held a memorial ceremony for Mattie Rice Clyburn, the daughter of Weary Clyburn, claiming her as a bona-fide ‘daughter of the Confederacy.’

Eight years later and watching this still makes me sick to my stomach.

It’s important to recognize that this particular exhibit and especially the museum itself are an indication of just how far the Lost Cause narrative has fallen in recent years. It reminds me of the large Confederate battle flags that in recent years have been placed along highways throughout the South.

Not too long ago Confederate flags flew atop state capitol buildings and in public spaces. The Lost Cause was enshrined in hundreds of monuments, public holidays and other public celebrations. Those days are long gone.

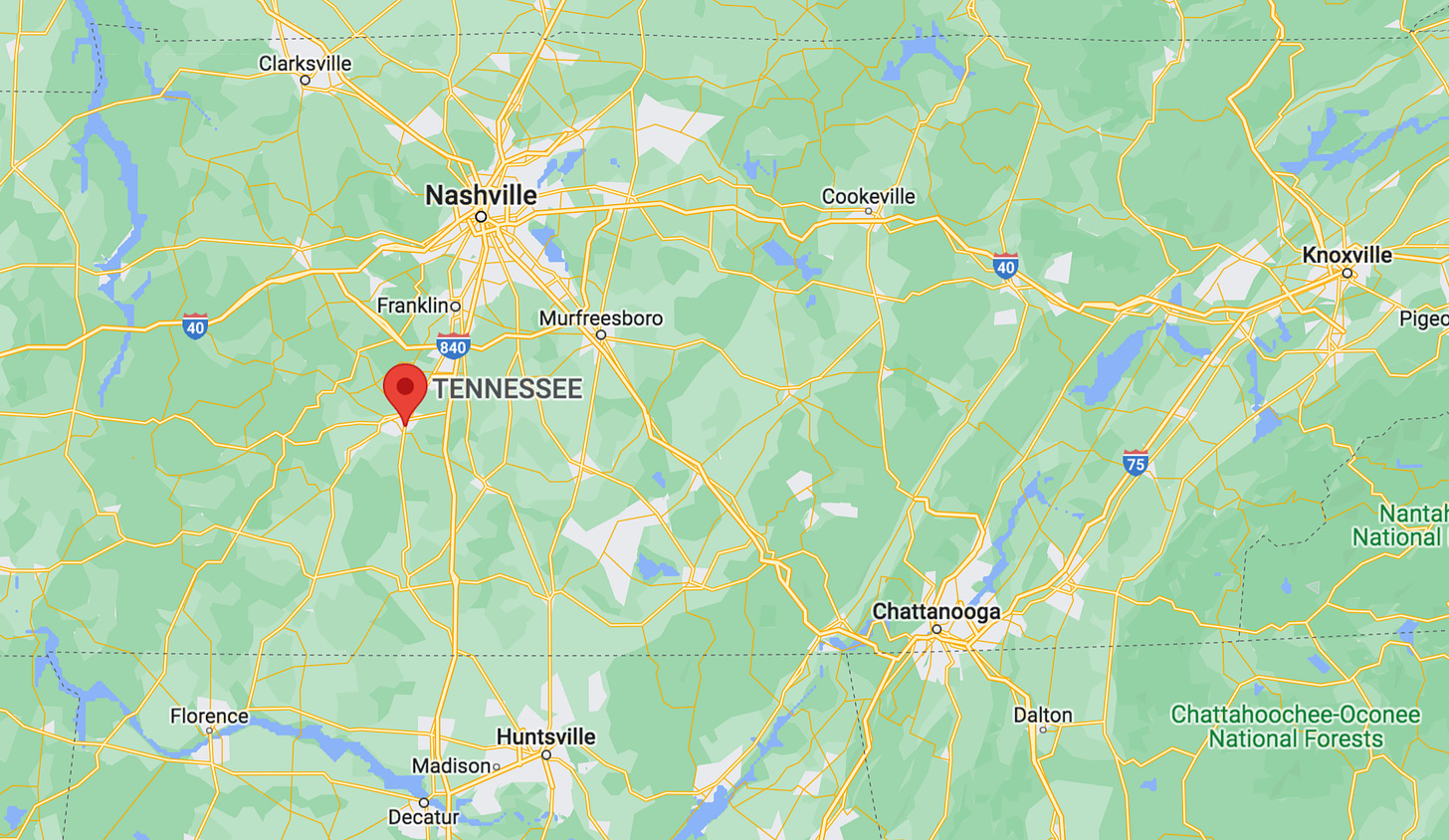

Today you have to travel to central Tennessee for your Lost Cause fix.

[Thanks to @liz_july4th on twitter for providing me with the above photographs from her recent visit.]

What’s ironic to me is that this museum is in east Tennessee, which on the whole had little use for the confederacy and actively worked towards ridding itself of the rebels.

Henry Wirz too. Classy.