Should You Watch Ken Burns's Civil War Documentary? (Part 3)

I've always thought that Barbara Fields was the real star of this film.

Check out Parts 1 and 2 in the series.

Update: Click here for the outtakes from Barbara Fields’s interviews for The Civil War.

In 1990 the story of emancipation and the complex chain of events that led to the end of slavery were located at the periphery of the nation’s collective memory of the Civil war. For many white Americans, their understanding of emancipation was either influenced by the Lost Cause and reconciliations or wrapped up in an equally distorted picture of Abraham Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator.”

One of the things that I have always appreciated about The Civil War is the extent to which the documentary shatters this simplistic and misleading narrative. Burns does this in a number of ways. He references key moments during the war such as the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation in Boston and along the Sea Coast Islands as well as the actions of the enslaved themselves and the entry of roughly 200,000 into the United States Army. Morgan Freeman gives voice to Frederick Douglass, who appears thirteen times during the series and brief appearances from Susie King Taylor, Christian Fleetwood, and Lewis Douglass are included as well.

The most important element in this “emancipationist” narrative, however, is Columbia University historian Barbara Fields. We spend so much time assessing Shelby Foote’s impact on the series that we don’t fully appreciate the role that Fields played.

Let’s keep in mind that while women are prominent in the field of Civil War history today, this was certainly not the case in 1990—even less so for African Americans. You may have briefly caught a glimpse of historians Edna Greene Medford or the late Armstead L. Robinson in an episode of Civil War Journal, but that’s about it.

For the vast majority of viewers of The Civil War in 1990 this would be their first exposure to a Black female historian. It would also be their first exposure to a more complicated narrative that centered the enslaved and emancipation in the overall narrative of the war.

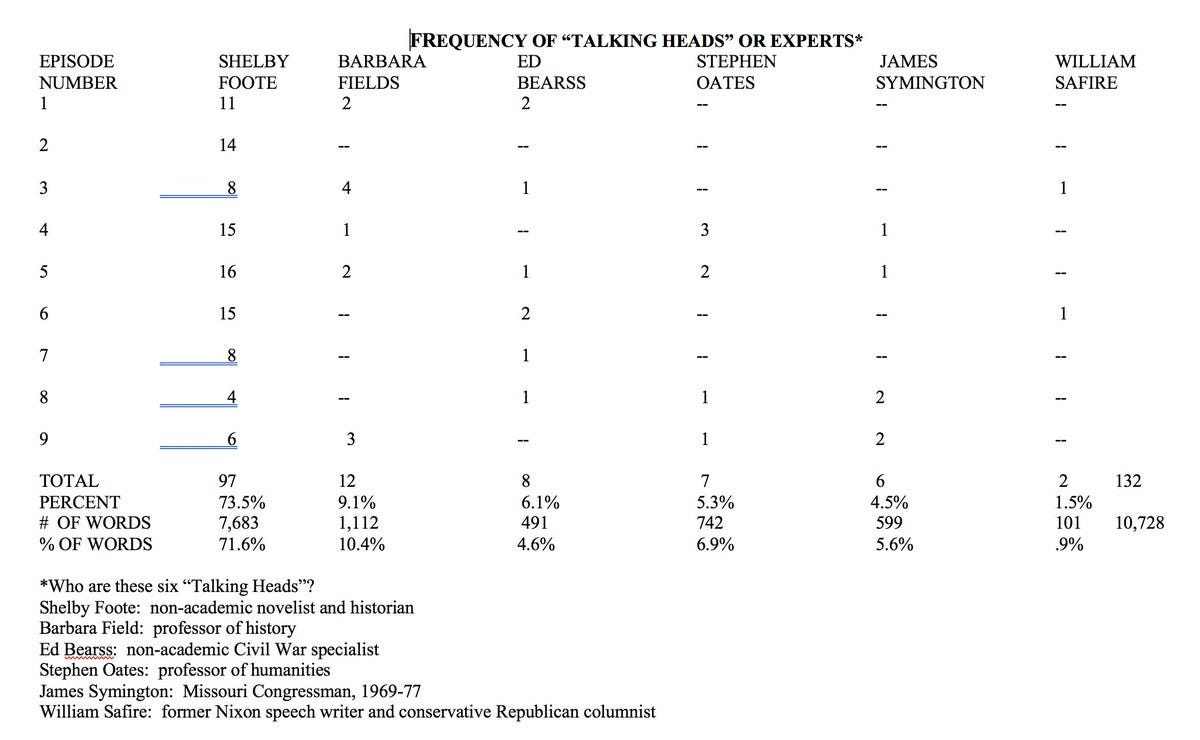

While we all know that Shelby Foote dominated the series as its most visible talking head, most people don’t appreciate the frequency of Fields’s commentary.

After Foote, Fields was the most visible talking head in the series and one of only two academic historians interviewed—the other being Stephen Oates. While Foote’s commentary falls on a wide spectrum of topics, Fields was largely confined to the story of emancipation and its legacy and the experience of African Americans. That narrow focus, in many ways, makes her comments more memorable than many of Foote’s colorful stories of owls scaring soldiers on sentry duty or Nathan Bedford Forrest’s daring escape before the surrender of Fort Donelson in April 1862.

Barbara Fields makes her first two appearances early on in Episode 1:

BF: For me the picture of the Civil War as a historic phenomenon is not on the battlefield. It’s not about weapons. It’s not about soldiers except to the extent that weapons and soldiers at that crucial moment joined a discussion about something higher: about humanity, about human dignity, about human freedom.

BF: If there was a single event that caused the war, it was the establishment of the United States in independence from Great Britain with slavery still a part of its heritage.

Both comments prepare viewers for a story that will go far beyond the popular narrative of battles and leaders. It also anticipates the ways in which Burns will integrate the story of emancipation into the more traditional military narrative. Battles and campaigns both influenced and were influenced by events elsewhere, including, as we shall see, the actions of the enslaved themselves.

Fields appears four times in Episode 3, which focuses on emancipation in 1862.

BF: It could have been a very ugly filthy war with no redeeming characteristics at all. And it was the battle for emancipation, and the people who pushed it forward – the slaves, the free black people, the abolitionists, and a lot of ordinary citizens – it was they who ennobled what otherwise would have been meaningless carnage into something higher.

BF: The slaves understood that that war was about slavery before it was a war… They made a nuisance for the army and they also made an issue that the army had to deal with. And if they army had to deal with it, the War Department had to deal with it. If the War Department had to deal with it, Congress had to deal with it. That means that every fugitive slave who made a nuisance of himself to the local commander eventually made a figure of himself to the Congress of the United States.

BF: I lose patience with the argument that because of someone’s time his limitations are therefore excusable or even praiseworthy…It is not true that it was impossible in that time and place to look any higher. Think of Wendell Phillips who, commenting on Abraham Lincoln’s proposal to colonize black people out of the country, was sarcastic. He said, “Colonize the blacks! A man might as well colonize his own hands or when the robber is in his house, he might as well colonize his revolver.”

BF: It’s hard to separate one issue from another. Obviously Lincoln had to win the war. He had to keep his respectability as president of a country that would not allow itself to be defeated by a group of rebels. So that was always an issue and it was especially an issue, of course, in 1862. He could not let himself be made a fool and the Union be made a fool by standing up for principles that could not be vindicated on the battlefield.

There are a couple themes here that are worth considering.

It is clear that Fields believes that the only outcome worthy of the sacrifice of so many on the battlefield was one that included the end of slavery—a point she alludes to in the first episode. This was specifically true for enslaved people, including those who eventually enlisted, as well as the abolitionists and those United States soldiers who were transformed after having been exposed to the horrors of slavery for the first time. Again, this is a point-of-view that had for a long time been overshadowed by a Lost Cause/reconciliationist narrative.

But while this was certainly true for those referenced above, Fields overlooks the fact that for the vast majority of the loyal citizenry of the United States, the preservation of the Union was the ultimate goal and was viewed as a higher calling and one worthy of the sacrifice.

I suspect that one of the reasons why Fields was so adamant in pushing this particular narrative is because at the time she was working with the Freedmen and Southern Society Project, which documents that role that enslaved men and women played in steering the nation toward emancipation. The wealth of documents collected will give you a sense of what Fields means in stating that the “slaves understood that that war was about slavery before it was a war.” [Do yourself a favor and spend some time perusing the wealth of documents at FSSP.]

This self-emancipation theory would have been brand new to white viewers of the series at the time and should not be minimized.

The embrace of emancipation as the war’s most important consequence and the actions of the enslaved in helping to bring it about also helps us to better understand her position re: Lincoln, colonization, and Union, though this is one of those places where I wanted to hear more from Fields.

Having demonstrated the role the enslaved played leading up to the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Fields drives home (Episode 4) the choice that many former slaves and freed Blacks made to enlist in the army.

BF: The people most affected by the Emancipation Proclamation obviously did not receive it as news because they knew before Lincoln knew that the war was about emancipation and moreover they knew, as perhaps Lincoln did without fully realizing it, and certainly as many people today do not realize, that the Emancipation Proclamation did nothing to get them their freedom. It said that they had a right to go and put their bodies on the line if they had the nerve to believe in it and many of them had the nerve to believe in it and many suffered for that.

The comment alludes to the treatment that many Black soldiers experienced at the hands of Confederates on the battlefield as well as the discrimination they faced in the Union army—all of which are explored further in the series.

Fields makes two appearances in Episode 5, the first in the introduction. She is followed immediately by the narrator David McCullough and a poem recited by Daisy Turner (age 104), the daughter of former slave, Alex Turner.

BF—When a black soldier in New Orleans said, “Liberty must take the day, nothing shorter,” he said, in effect, that when we count up those who have died, when we survey the carnage, it must be for something higher than Union and free navigation of the Mississippi River… During the summer of 1863…a convention of free black people demanded the right for… black men to take part in the struggle as soldiers. And their key resolution said, “It is time now for more effective remedies to be thoroughly tried in the shape of warm lead and cold steel duly administered by 100,000 black doctors.”

DM—Early in the war, a fugitive slave named Alex Turner had made his way north and joined the 1st New Jersey Cavalry. In the spring of 1863 he guided his regiment back to his old plantation at Port Royal, Virginia and killed his former overseer.

When the war was over he went to New England and found work as a logger. In 1883, his daughter Daisy was born.

DT: Dear Madam, I am a soldier,/ And my speech is rough and plain,/ I’m not much used to writing,/ And I hate to give you pain,/ But I promised I would do it,/ And he thought it might be so,/ If it came from one that loved him/ Perhaps it would ease the blow./ By this time you must surely guess/ The truth I feign would hide,/ And you pardon me for rough soldier words,/ While I tell you how he died.

This sequence is incredibly powerful and points to a much longer narrative of slavery to freedom. The story of Alex Turner is a literal reminder that the only way to end slavery by 1863 was to kill it. In Turner we see one of countless examples of how the actions of the enslaved transformed the war and, in turn, their own lives. The appearance of his daughter in the film must have driven this point home for viewers and also serve as a reminder of how close we still were to the war and slavery in 1990.

One final comment from Fields before I wrap this up. It comes at the end of Episode 5, much of which is focused on the Gettysburg Campaign.

BF—Many of the Union soldiers who began with stereotypical assumptions about black men, who assumed that they couldn’t fight, and they would hand their weapons over to the enemy, that they would run and so on, had their minds changed in the grimmest circumstances. And some of the documents that tell the story of how people’s ideas were transformed are not the sort of documents that you enjoy reading because they speak of how people became companions in death, of how white soldiers learned to respect their black comrades when they watched how they reacted as people all around were being killed, being butchered.

I think this is one of the ways in which The Civil War anticipated future scholarship. Historians have written a good deal in recent years about the ways in which Union soldiers were impacted by confronting enslaved people. I’ve written about this in connection to Robert Gould Shaw, who would eventually command the first Black regiment raised in the North.

You may also want to read Chandra Manning’s book, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War as well as Kristopher A. Teters, Practical Liberators: Union Officers in the Western Theater during The Civil War and Jonathan Noyalas, Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley During the Civil War Era. Perhaps the authors were influenced to pursue these topics by Fields and the film.

I am going to consider Fields’s final comments in the next installment, which will look at how Ken Burns interprets the end of the war and its legacy.

Thanks for reading.

This is eye opening. I was unaware of Ms. Fields and her work before reading this. I look forward to seeing and reading more from her, she has an important and little heard perspective. Ken Burns was smart to include her.

Thanks so much for such a great post.

Kevin, loved this series on Burns, especially this installment on Fields. One thing I found interesting is the number of times that Burns used Foote and Fields edited back-to-back to subtly show some disagreement, particularly when discussing the causes of the war. It should also be noted that Fields' work with the Freedom project and her high-profile comments about emancipation in the Burns series played a role in the "who freed the slaves" debate that caused even James McPherson to weigh-in in the 1990s. That debate pulled me in, as I felt like there had to be a middle ground, but I also felt that blacks did more to turn the conflict into a war of emancipation than just create a "contraband" problem that Lincoln had to solve (which Fields emphasizes). Thus, my own book (to some degree) was sparked by Fields’ comments in the series.