Yesterday I came across this tweet from historian Michael Beschloss.

There are any number of ways one could react to people who insist that, “Lincoln should have simply allowed the South to secede in 1861.” First, we could push back against the wording of the question itself. Not all of the Southern states seceded between December 1860 and May 1861. The slaveholding Border States of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware remained in the Union throughout the war.

We could point out that “the South” almost always means the white South and ignores roughly half the population of the slaveholding states in 1860-61. And if we are really on our A-game, we could point to the large pockets of Unionism throughout the South.

My larger problem is in failing to turn the question into an opportunity to learn a little history. Most people who speculate about what Lincoln should have done have no real understanding of why he did what he did. More to the point, few people have any sense of what the Union meant to the loyal citizenry of the United States in 1860-61.

Of course, we have a very clear picture of what Union meant to Lincoln and why he didn’t simply allow the Southern states to destroy the nation. You could wade through his careful examination of the creation and expansion of the nation and the relationship between the states and the federal government in his February 27, 1860 address at Cooper Union Institute in New York City:

You say we are sectional. We deny it. That makes an issue; and the burden of proof is upon you. You produce your proof; and what is it? Why, that our party has no existence in your section - gets no votes in your section. The fact is substantially true; but does it prove the issue? If it does, then in case we should, without change of principle, begin to get votes in your section, we should thereby cease to be sectional. You cannot escape this conclusion; and yet, are you willing to abide by it? If you are, you will probably soon find that we have ceased to be sectional, for we shall get votes in your section this very year. You will then begin to discover, as the truth plainly is, that your proof does not touch the issue. The fact that we get no votes in your section, is a fact of your making, and not of ours. And if there be fault in that fact, that fault is primarily yours, and remains until you show that we repel you by some wrong principle or practice. If we do repel you by any wrong principle or practice, the fault is ours; but this brings you to where you ought to have started - to a discussion of the right or wrong of our principle. If our principle, put in practice, would wrong your section for the benefit of ours, or for any other object, then our principle, and we with it, are sectional, and are justly opposed and denounced as such. Meet us, then, on the question of whether our principle, put in practice, would wrong your section; and so meet it as if it were possible that something may be said on our side. Do you accept the challenge? No! Then you really believe that the principle which "our fathers who framed the Government under which we live" thought so clearly right as to adopt it, and indorse it again and again, upon their official oaths, is in fact so clearly wrong as to demand your condemnation without a moment's consideration.

There is also his July 4, 1861 speech in which Lincoln spoke eloquently about the United States as the “last best hope of Earth” and the importance of maintaining free and fair elections.

This is essentially a people's contest. On the side of the Union it is a struggle for maintaining in the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men; to lift artificial weights from all shoulders; to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all; to afford all an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life. Yielding to partial and temporary departures, from necessity, this is the leading object of the Government for whose existence we contend….

Our popular Government has often been called an experiment. Two points in it our people have already settled--the successful establishing and the successful administering of it. One still remains--its successful maintenance against a formidable internal attempt to overthrow it. It is now for them to demonstrate to the world that those who can fairly carry an election can also suppress a rebellion; that ballots are the rightful and peaceful successors of bullets, and that when ballots have fairly and constitutionally decided there can be no successful appeal back to bullets; that there can be no successful appeal except to ballots themselves at succeeding elections. Such will be a great lesson of peace, teaching men that what they can not take by an election neither can they take it by a war; teaching all the folly of being the beginners of a war.

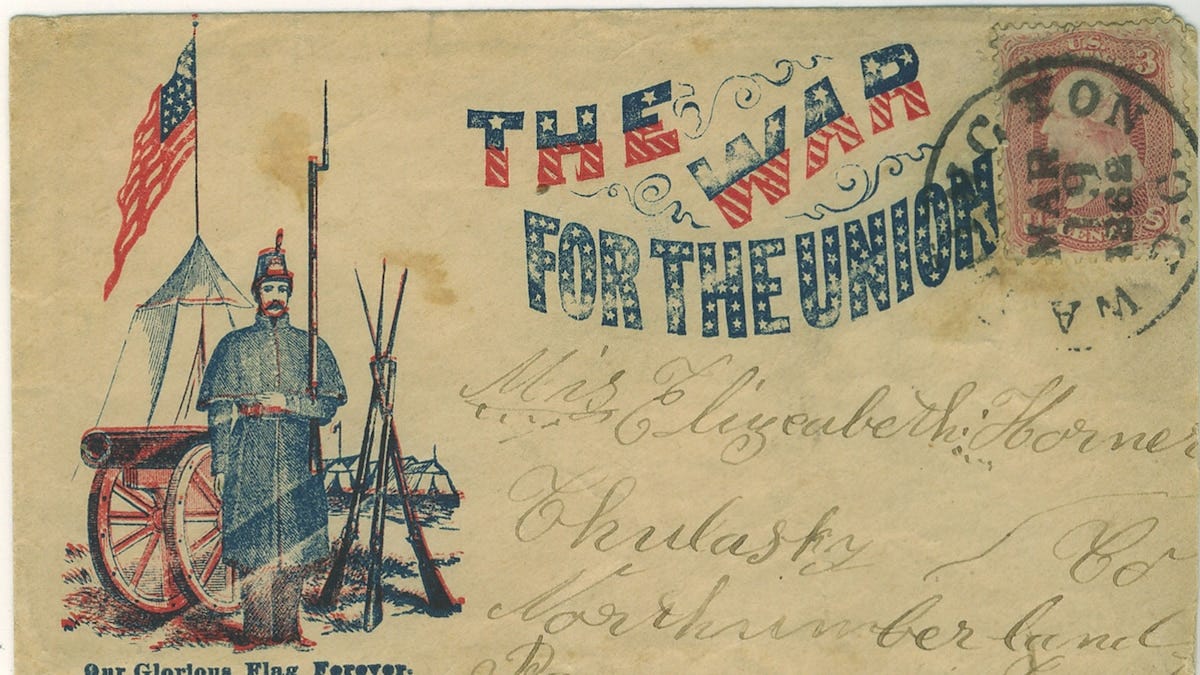

But this question isn’t just about Lincoln. We also need to know something about why tens of thousands of loyal Americans volunteered in the opening months of the war to help save the Union. Why were young men from states as far away as Wisconsin and Maine—states that were under no immediate military threat and would likely never be—willing to give their lives in this cause?

Historian Gary Gallagher is right that few Americans today have any sense of what Union meant to the vast majority of Americans during the Civil War. His book The Union War is a wonderful place to begin to put the pieces together, but here is how he sums it up:

Anyone interested in why the mass of northern people supported crushing the rebellion, even at hideous cost, must come to grips with the crucial fact. Union was key, and for many in the loyal states it had a meaning that extended far beyond the United States. Victory meant keeping aloft the banner of democracy to inspire anyone outside the United States who suffered at the hands of oligarchs. It meant affirming the rule of law under the Constitution and punishing slaveholding aristocrats whose selfish actions had compromised the work of the founding generation. And it meant establishing beyond question a northern version of the nation—of America, of the United States—that left control in the hands of ordinary voting citizens who were free to pursue economic success without fear of another disruptive sectional crisis. (p. 34)

Finally, and arguably most importantly, the question of whether Lincoln should have done x or y treats him as a means to an end. It uproots Lincoln and much of the rest of the population from history itself to help someone make an argument that has very little, if anything, to do with history.

Encouraging a response to the question above invites sloppy thinking. Just read through the responses to the Beschloss’s tweet. This was a great opportunity to ask people to step back from the question itself and think about the importance of historical context.

It’s hard enough just to try to figure out what happened and why. What do you think?

I understand where you're coming from, Kevin, regarding this being the wrong question. If we look at the question, though, what it's asking in reality is why didn't Lincoln ignore his oath of office and his constitutional duty, and why didn't he usurp Congressional authority? Lincoln had no authority to allow states to secede. The Constitution gives Congress the authority to admit states, therefore Congress has the authority to release states from the Union, not the President. The President is charged with executing the laws, including the laws that make states part of the United States. Had Lincoln not resisted secession he would have been derelict in his duty. The answer, then, as to why Lincoln did not allow the states of the confederacy to leave the United States is Lincoln had integrity.

Was "peaceful separation" even possible? Lincoln's platform was restricting slavery to where it already existed. Both he and the slaveholders were clear that this would in due course make slavery uneconomic. The slaveholders demanded the right to extend slavery anywhere in the Territories and the yet-to-be-conquered West. The North generally wanted the same lands for free settlement. Therefore "peace" with the Confederacy would surely have been followed by wars over possession of the new western lands.