I am feeling overwhelmed after having spent most of the day following the story of Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts here in Beaufort, South Carolina. I was fortunate that NPS historian Christopher Barr blocked off his schedule to take me around. His knowledge of this history and the broader history of the Civil War and Reconstruction in and around Beaufort is extensive and his passion was evident at every step. Reconstruction Era National Historical Park is in very good hands thanks to Chris and his staff.

The highlight of the day was the Beaufort National Cemetery—one of the first national cemeteries established for fallen United States soldiers during the Civil War. Chris made it a point to remind me (on more than one occasion) that locals rightfully regard the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry and not the 54th Massachusetts as the first Black regiment raised by the U.S. military. The regiment was commanded by Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson. With that in mind we stopped at their section of the cemetery first.

It’s an emotional experience standing among formerly enslaved men from the region, who volunteered to fight for a nation that was not at all prepared to recognize them as citizens or even committed to the end of slavery in 1862.

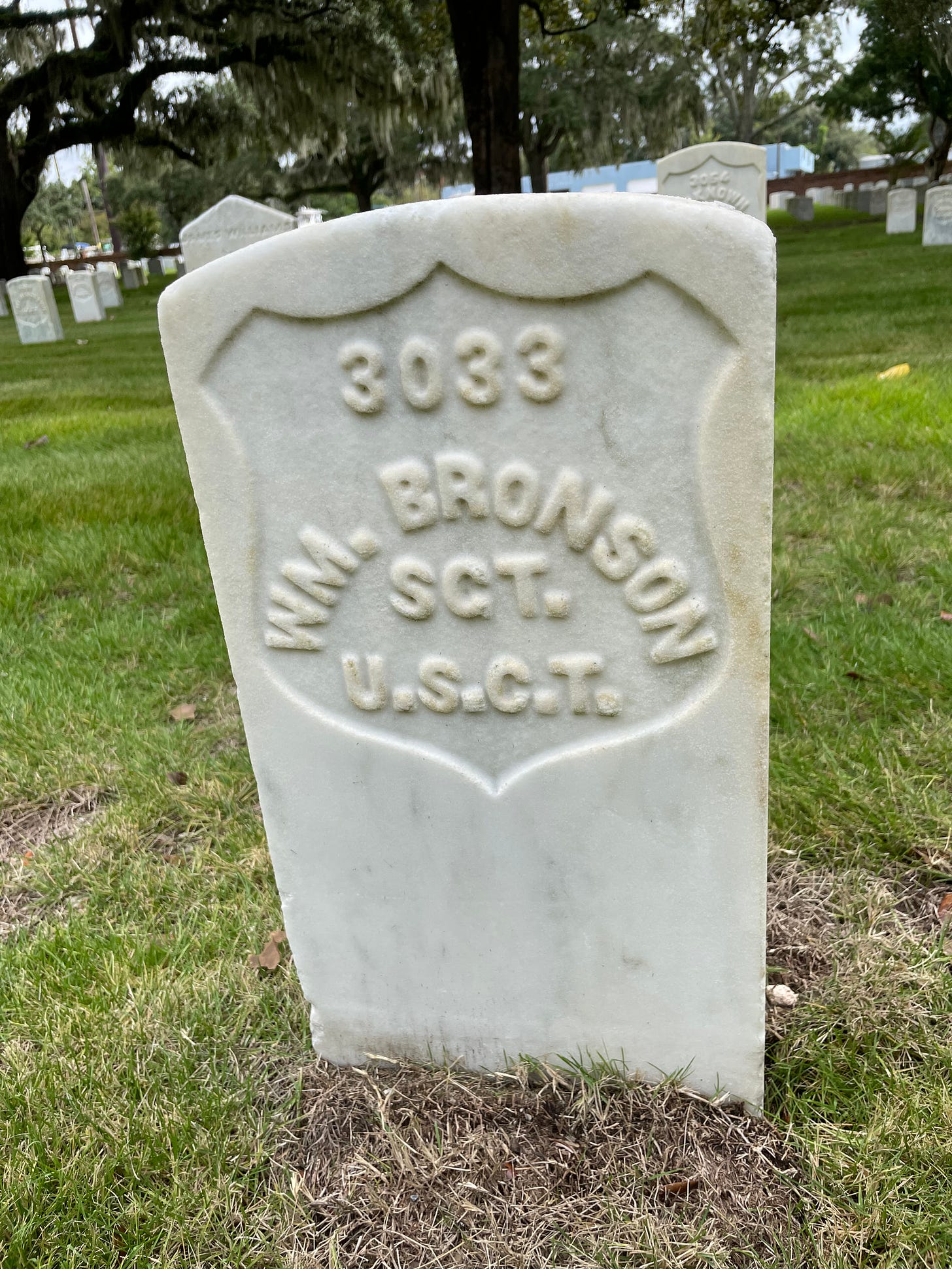

The regiment was unofficially formed by General David Hunter in May 1862. William Bronson was the first to enlist.

In other words, Bronson was the first of the first—the first enlistee in the first all-Black regiment raised by the U.S. military. I don’t mind admitting that I felt a chill go down my spine when Chris shared Bronson’s story with me.

This is a turning point in American history if ever there was one.

Bronson didn’t survive the war, but Sgt. Prince Rivers, who also served in the 1st South Carolina did. After the war he purchased property in downtown Beaufort that is now a parking lot. If I remember correctly, Rivers operated a liquor store on the site of the chocolate store. [By the way, the box of chocolates used in the movie Forrest Gump was purchased in that store.]

Rivers purchased a magnificent home just across the street from the parking lot. Many of you will be happy to hear that historian Steve Berry is currently working on a biography of Rivers.

The extent of Black property ownership in and around Beaufort makes this an ideal place to explore the ‘slavery to freedom’ narrative and the broader history of Reconstruction, but as Chris rightly pointed out, it also has its challenges given that the story of Black property ownership after the war (especially on St. Helena’s Island) is an exception to the rule.

Back at the cemetery we stopped at a relatively new grave plot. In 1987 the remains of nineteen Black soldiers in the 55th Massachusetts were discovered on Folly Beach on Folly Island. The regiment was encamped there in the summer of 1863. Two years later their remains were reinterred in Beaufort National Cemetery.

On May 1, 1865, roughly 10,000 Black Charlestonians commemorated the 260 Union soldiers buried at the Washington Race Course, a Charleston horse track that had been converted into an outdoor prison for captured Northerners. Historian David Blight wrote the following about what took place that day:

The day’s events began around 9 a.m. with a parade led by about 2,800 Black schoolchildren, who had just been enrolled in new schools, bearing armfuls of flowers. They marched around the horse track and entered the cemetery gate under an arch with black-painted letters that read ‘Martyrs of the Race Course.’ The schoolchildren proceeded through the cemetery and distributed the flowers on the gravesites.

Other attendees entered the cemetery with even more flowers, as the schoolchildren sang songs including ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ and ‘John Brown’s Body.’

‘When all had left,’ Redpath wrote, ‘the holy mounds — the tops, the sides, and the spaces between them — were one mass of flowers, not a speck of earth could be seen; and as the breeze wafted the sweet perfume from them, outside and beyond, to the sympathetic multitude, there were few eyes among those who knew the meaning of the ceremony that were not dim with tears of joy.’

The dedication ended with prayers and Bible verses from local Black ministers, followed by speeches from Union officers and Northern missionaries, a picnic on the racecourse and drills by Union infantrymen, including some African American regiments. The observance didn’t end until sundown.

According to Blight, this is very likely the first documented celebration of what became Decoration Day and later Memorial Day.

Imagine my surprise when Chris walked me to a memorial on site honoring the “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

These soldiers are buried in unmarked graves nearby. The reinterments of these men in the years immediately following the Civil War took place as part of a broader federal reburial effort that also incluced nearby Morris Island, where the 54th Massachusetts and Robert Gould Shaw assaulted Battery Wagner on July 18, 1863.

As all of you know, Shaw’s body was buried in a mass grave with his Black men. Confederates intended this as an insult, but Shaw’s family considered it an honor and refused to have his body removed when the opportunity arose. Robert’s father laid out his family’s demands in a letter to military officials in South Carolina:

We would not have his body removed from where it lies surrounded by his brave & devoted soldiers, if we could accomplish it by a word. Please to bear this in mind & also, let it be known, so that, even in case there should be an opportunity, his remains may not be disturbed.

The federal reburial effort on Morris Island likely included the removal of Shaw’s body to an unmarked grave in the Beaufort National Cemetery.

The marble posts are the unmarked graves that you see in these two photographs below. I did my best to hold it together emotionally. I’ve followed Shaw’s path now for more years than I want to count. Though we can’t be certain that he is buried here, there is a good chance that I walked within a few feet of his remains.

Finally, we stopped at the section of the cemetery where members of the 54th Massachusetts are buried.

Charles K. Reason enlisted in Company E of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry on March 29, 1863 in Syracuse, New York. He was wounded in the assault on Battery Wagner and died of his wounds at one of the hospitals in Beaufort, South Carolina on July 27, 1863.

Dr. Esther Hill Hawks was with him when he died, and in one of her final conversations with him, he declared: As soon as the government would take me I came to fight, not for my country, I never had any, but to gain one.

There were roughly 15 hospitals operating in Beaufort at the time. After the failed assault on Wagner, most of the wounded men in the 54th Massachusetts were brought to Hospital No. 6, also known as “The Castle.” [Notice the witness tree in the front yard to the right of the stairs.]

An outbuilding behind the home served as a makeshift morgue for the soldiers. Charles Reason’s body, along with his fallen comrades, would have been moved here after they succumbed to their wounds.

I am going to bring this post to an end. I am still processing everything that I’ve seen today so stay tuned for additional reflections and many more photographs. I’ve used the word “overwhelming” a number of times over the past few days to describe my experiences here, but it really is appropriate.

For now I want to thank Chris Barr once again for taking the time to show me around. Chris and everyone else in the NPS system perform an invaluable service for all of us. They are the caretakers of some of our most important historic sites and natural resources across the country. The looming federal shutdown will directly impact this employees and their families. They deserve so much better.

Here’s hoping that our elected leaders can once again figure a way out of a mess of their own doing.

The brother of my great-great-great grandfather is one of the "Martyrs of the Race Course". Isaac Rice and his twin brother Abraham were POWs in Andersonville and were moved to Charleston when Sherman was getting close. Isaac died in Charleston September 24, 1864 and was buried along with others in an unmarked grave. He now lays in Beaufort with the others. He is mistakenly identified as M.L. Rice

Great stuff, Kevin. That park needs more publicity. I'm surprised, given the location, how reasonable the hotel costs are. We have an unscheduled trip to that part of the country in our indefinite future, and I may insist on a detour there. Looking forward to the book.