It doesn’t take long when reading the letters and diaries of Civil War soldiers to appreciate just how fragile the bonds are that connect us to the people we love. Some of Robert Gould Shaw’s most touching letters were written during major holidays like Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Such letters cut through the routines of camp life and highlight those things that make life joyous and meaningful.

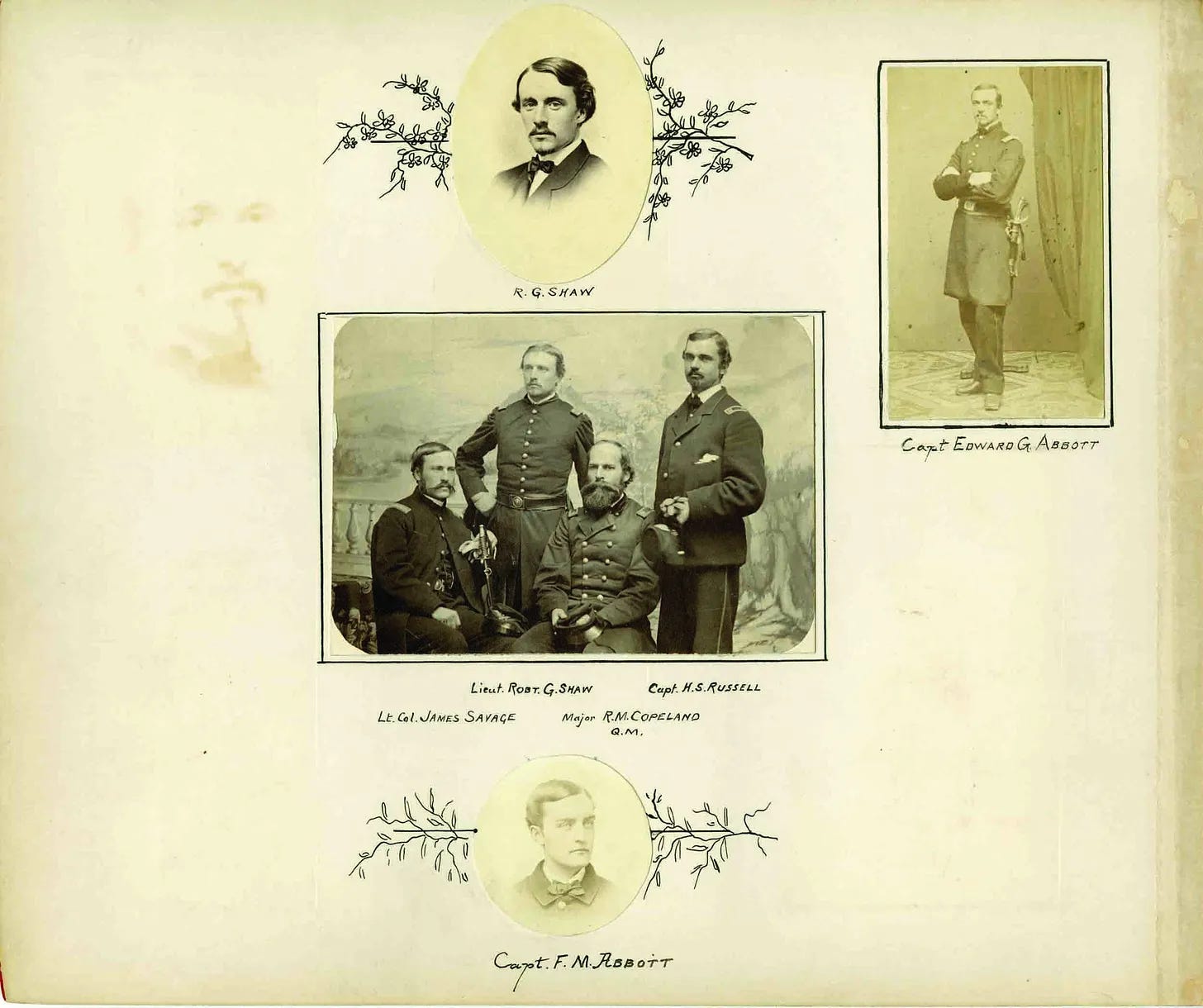

Shaw had formed a bond with many of his fellow officers since leaving Boston in June 1861 as part of the Second Massachusetts Regiment. Like Shaw, many were former Harvard students and hailed from some of Boston’s most elite and wealthy families. They shared a similar cultural and political outlook. In camp they relied on one another for support and comradeship.

They relied on one another to survive the chaos and inevitable loss of war.

Shaw and his closest friends shared extended periods of time together between campaigns. They shared letters from their respective families, recited poetry, and read literature to one another. Here is one of those moments described by Shaw in November 1861.

We have had a cold, rainy, and intensely uncomfortable day, but I have a nice little stone fireplace in my tent, with a pretty high chimney outside, which make it draw finely, and keep the tent warm and dry. In this camp, mine happens to be one of the successful fireplaces (they often smoke), so that I have had company all day. We have been, from reveille until tattoo, talking and reading, and having quite a nice time. Stephen Perkins, Rufus Choate, and Captain Savage were the guests. The latter is one of the best men I have ever known, and, at the same time, he is one of the best officers, and a real brave fellow. One of the rarest articles to be found is a pure-minded man, and Savage is as much so as any woman.

This was about more than simply finding ways to occupy themselves. Shaw and his comrades were attempting to recreate their cultural world in the middle of an encampment. There conversations and reading material reflected a broader view of the world that reinforced their sense of themselves as elites and what it was that they were fighting for.

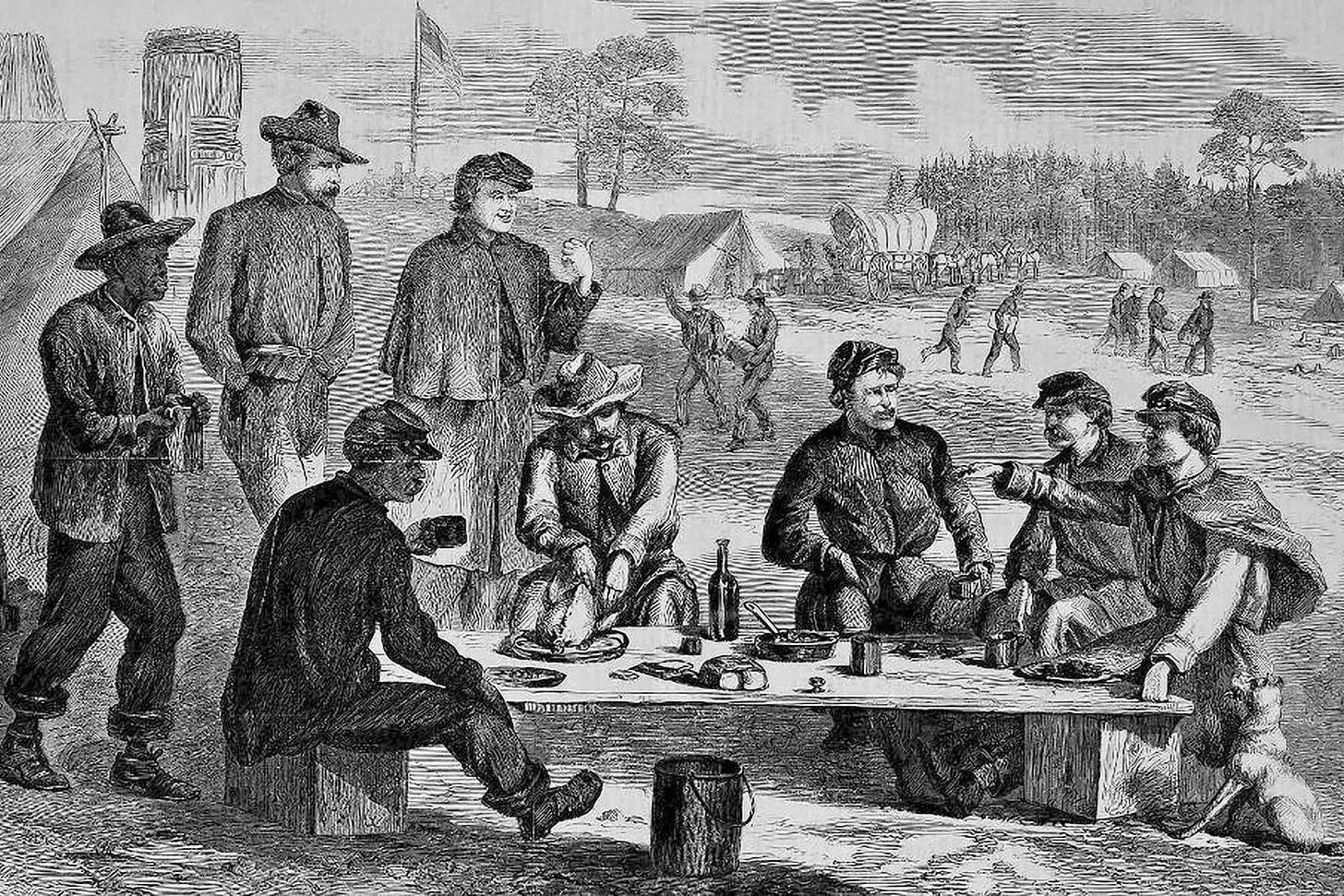

A few weeks later, Shaw and his fellow officers gathered for their first Thanksgiving away from home. Despite being away from home, it proved to be a joyous occasion. The regiment was still intact, not yet having experienced their first major battle. The men pooled their packages of cakes and other food items to round out their dinner.

We had a fine time on Thanksgiving. Day. The men enjoyed themselves very much. In the morning we had a divine service, after which there was a turkey-shoot; and at 12 1/2 P.M. the men had their dinner. Besides all the turkey and geese, they had nearly twelve hundred pounds of plum-pudding. The officers dinner was at 5 o’clock, and we enjoyed ourselves very much. Our mess-tent was gorgeously lighted with candles, bayonets serving for candlesticks, and the dinner was excellent. (November 23, 1861)

One year later, the scene was very different. All that was left was an empty table, memories, and an uneasiness as to what was to come.

The fighting in the spring and summer of 1862 had devastated the junior-officer corps in the Union army, including the Second Massachusetts. A number of Shaw’s closest friends had either been killed or wounded at the battles of First Winchester, Cedar Mountain, and Antietam. He was lonely and emotionally drained. The strong feelings of loss are palpable in everything Shaw wrote during this period.

On this day in 1862, Robert Gould Shaw sat down in his tent near Sharpsburg, Maryland—the sight of the bloody battle of Antietam fought just two months earlier—to share a few words about his Thanksgiving celebration with his family back home.

Yesterday was Thanksgiving, and we managed to have a very pleasant day. There would have been no drawback, if we hadn’t missed from the table so many faces which were there last year at this time. This made the dinner a very quiet affair compared with most bachelor parties. Besides the seven officers killed last summer and this autumn, there are a good many at home wounded and ill; so that the society is materially changed since we came out. It is very strange and unfortunate, that the officers that have been killed were the very best we had, both as comrades and as military men. No doubt, after a man is dead his virtues only are remembered, but in our case the dead ones really were the best. (Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune, p. 263)

It’s a heartbreaking letter, whose sentiments were repeated in thousands of other letters sent home to family’s across the country to mark the day’s festivities.

The one bright spot during this period for Shaw was his engagement to Annie Haggerty. The two would marry the following May in New York City, just three weeks before Shaw sailed to South Carolina as the colonel of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts.

Roughly eight weeks later, Shaw was killed while leading his regiment in the assault on Battery Wagner.

I hope all of you have the opportunity today to spend Thanksgiving with friends and family, but I am also aware that for some of you this may not be possible. In that case, I wish for you a day of peace and comfort.

Happy Thanksgiving to all of you.

I’ve been to the memorial to Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts in Boston. It’s a moving and fitting memorial to a brave group of patriots. Thank you for this essay, and Happy Thanksgiving to you.

Very nice essay. I think one of the historian’s roles is to help people of the present see the past through the eyes of the people of the past. You are good at doing that.