Robert Gould Shaw awoke on September 18, 1862 within feet of roughly twenty dead “Rebel” soldiers. He had survived the previous day’s bloody fighting in and around the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland and along the Antietam Creek, which had left thousands of dead and wounded. It would be remembered as the single bloodiest day in American history.

The battle had brought to a close months of active campaigning for Shaw and the Second Massachusetts, beginning with the battle of Front Royal on May 23, followed by Cedar Mountain on August 9, and finally Antietam.

The war in 1862 had decimated the officer corps of the Second Massachusetts, many of whom Shaw counted as close friends.

Shaw characterized Antietam as the “greatest fight of the war,” but struggled to capture the scale of the violence in letters home. “Every battle makes me wish more and more that the war was over. It seems as if nothing could justify a battle like that of the 17th, and the horrors inseperable from it.”

President Lincoln would have disagreed with this assessment. Although the Army of the Potomac did not destroy Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia it did manage to push Confederates back across the Potomac into Virginia. After a summer of battlefield defeats and a Confederate offensive into Maryland it was close enough to count the battle as a victory.

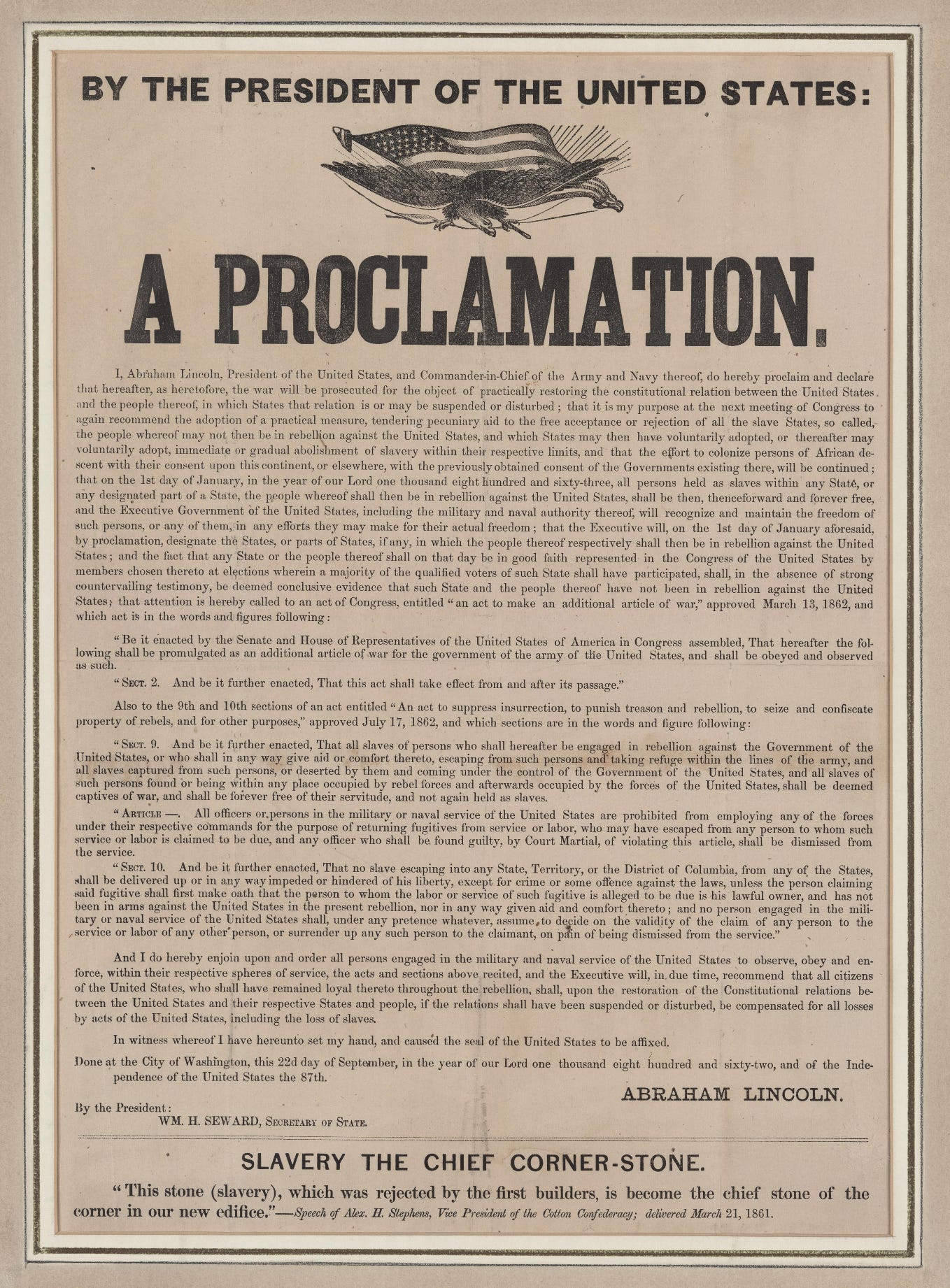

Five days later on September 22, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation gave the states in rebellion until the end of the year to surrender their arms with the intent to rejoin the Union. Failure to do so would result in the emancipation of all enslaved people living in areas not occupied by the United States army on the first of the new year and turn every soldier into a liberator of slaves. Wherever the army moved, slavery would be effectively abolished.

Shaw received word about Lincoln’s proclamation and discussed its significance with his friends in camp and especially with his parents back home. It’s important to remember that Shaw did not interpret the scope of the proclamation and its likely impact in a vacuum. The proclamation followed a tug of war between Lincoln and commanders like John Fremont and David Hunter, who took steps to abolish slavery in their military districts only to have the president revoke their orders. A string of congressional acts and presidential orders relating to slavery and emancipation, beginning with the First and Second Confiscation Acts as well as an act abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C. in April 1862 gradually eroded slavery on Lincoln’s own terms.

Even more importantly, Shaw had personally witnessed the exodus of thousands of enslaved people, beginning with the arrival of Federal forces in the Lower Shenandoah Valley in July 1861 and again in February 1862. The arrival of the army functioned as a catalyst for enslaved people in the Valley and elswhere seeking freedom. Their actions, more than anything else, helped to undercut the institution of slavery and influence the views of Union soldiers, who had never experienced the horrors of slavery or interacted with the enslaved.

For Shaw, the question of what to do about slavery hinged almost entirely on its impact on military affairs and the course of the war. Shaw wrote home to his mother on hearing the news of the proclamation:

So the ‘Proclamation of Emancipation’ has come at last, or rather, its forerunner. I suppose you are all very much excited about it. For my part, I can’t see what practical good it can do now. Wherever our army has been, there remain no slaves, and the Proclamation will not free them where we don’t go. Jeff Davis will soon issue a proclamation threatening to hang every prisoner they tak, and will make this a war of extermination… The condition of the slaves will not be ameliorated certainly, if they are suspected of plotting insurrection, or trying to run away; I don’t mean to say that it is not the right thing to do, but that, as a war measure, the evil will overbalance the good for the present. Of course, after we have subdued them, it will be a great thing.

There is a good deal of tension that comes across in Shaw’s correspondence with his parents in 1861 and 62, especially around the issue of slavery and emancipation. For his parents the central goal of the war was the destruction of slavery. Military decisions, as far as they were concerned, should and must advance the goal of emancipation. They rarely distinguished between the moral question of emancipation and military expediency.

“Hesitancy is excusable in such a mighty question as the sudden emancipation of our poor slaves, even as a military necessity,” Sarah wrote to an overseas correspondent in July 1862, “but I wish Mr. Lincoln would dare to do right, and trust that our Heavenly Father would see that no evil should come of it.” “We are as a nation expiating dreadful sins of long standing, and we are being purified by fire, but the end will come.”

Shaw’s mother apparently responded to her son in a similar manner given his letter of October 5th:

Don’t imagine, from what I said in my last, that I thought Mr. Lincoln’s ‘Emancipation Proclamation’ not right; as an act of justice, and to have real effect, it ought to have been done long ago. I believe, with you, that the closer we adhere to Right and Justice, the better it will be in the end, and that, if we want God on our side, we must be on His side; but still, as a war-measure, I don’t see the immediate benefit of it, and I think much of the moral force of the act has been lost by our long delay in coming to it.

Mother and son occupied two very different perspectives on the question of emancipation, the former influenced by a lifetime’s embrace of reformist principles and the latter by the challenges that the war itself posed on the ground day in and day out.

For Shaw, the question of whether the proclamation was “right” or “an act of Justice” was not ultimately what mattered to him at the front. What mattered was whether it would bring the nation one step closer to military victory. In that sense, Shaw subscribed to what I believe was the dominant view of slavery and emancipation in the summer of 1862 within the rank and file.

I don’t believe that Shaw ever fully embraced his parent’s abolitionist zeal before his death leading a Black regiment in the assault on Battery Wagner on July 18, 1863. As a young boy he announced to his parents that he ‘did not want to be a reformist.’

Shaw’s eventual acceptance of the colonelcy of the 54th Massachusetts can only be understood if we look closely at how he struggled to make sense of a constantly shifting political, social, and racial landscape during those first 18 months of the war—including moments like today’s 160th anniversary of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Very interesting. Another reminder that people are complex.

This nuance adds great interest to Shaw's story. Thanks!

While I sympathize with Sarah Shaw's passion, acting boldly and trusting God to handle the fallout isn't terribly practical. In quite a different historical setting, Philip II used to tell his commanders to count on God in the same way; one of them pointed out that God would "tire of working miracles for us", as the fate of the Armada proved.