Public memory of Robert Gould Shaw is tied, almost exclusively, to the brief period he spent in command of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment—the first Black regiment raised in the United States in early 1863. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s beautiful monument celebrating Shaw and the 54th on the Boston Common and the 1989 Hollywood movie Glory are largely responsible for this.

One of the things I am trying to emphasize in my biography of Shaw are the roughly nineteen months that he spent in the Second Massachusetts. Shaw was commissioned a second lieutenant and was eventually promoted to captain after the battle of Antietam.

This period, in my view, is absolutely essential to understanding his personal struggle to agree to take command of the 54th and the brief period in which he was in command of the regiment before his death in July 1863.

At the center of this section of the project are the ways in which comradeship and friendship helped to shape Shaw’s experience in the Second Massachusetts.

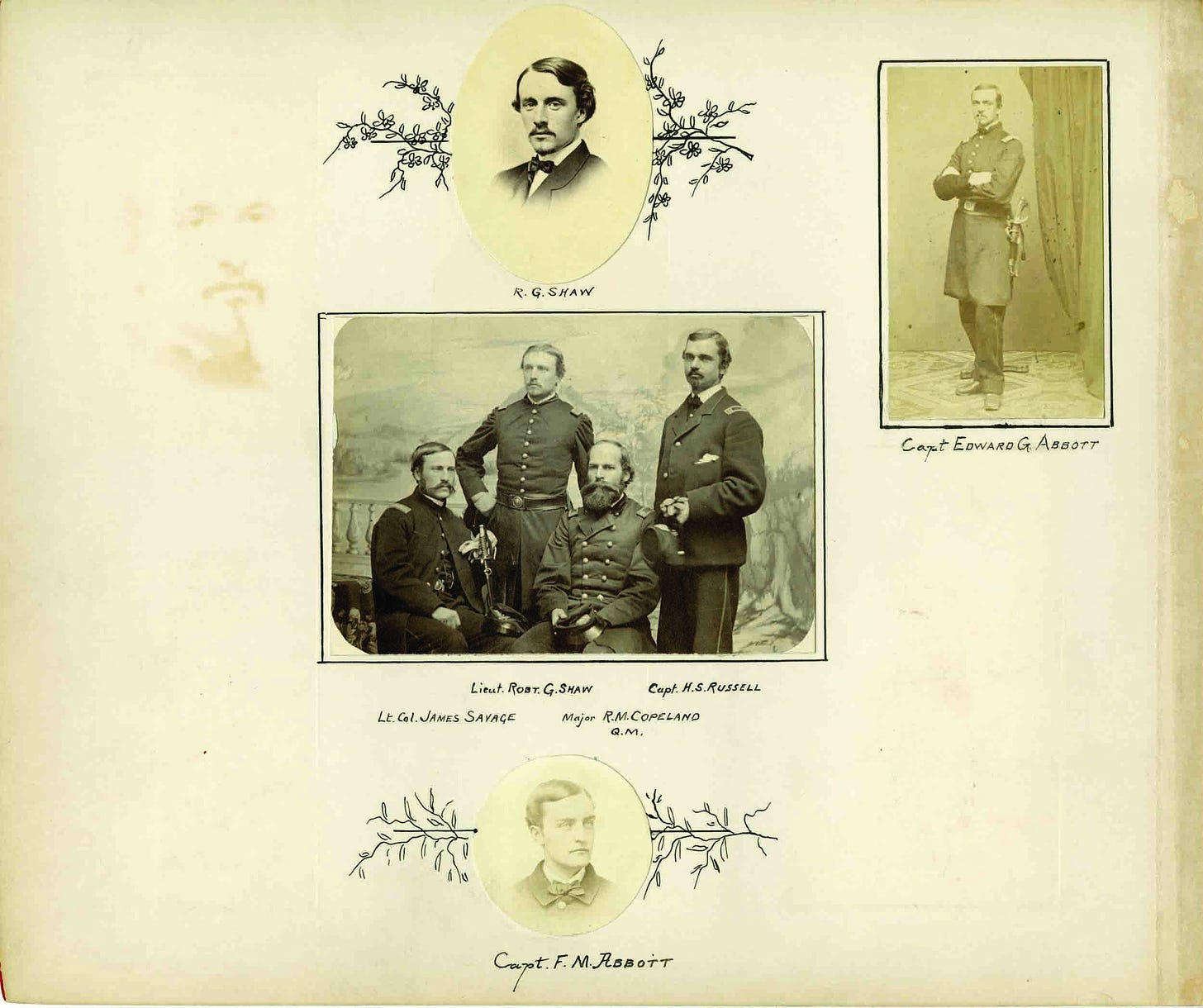

The image above of Shaw alongside his fellow officers point to some incredibly important friendships that were nurtured during this period of the war. I’ve been reading as many letter/diary collections from these men to get a feel for life in the regiment and more specifically their interactions with one another.

Most of these men hailed from elite families and attended and/or graduated from elite schools like Harvard. They shared similar assumptions about the purpose of the war, including what should be done about slavery and how civilians should be treated, but they were also challenged to think anew about these and other issues as the war dragged on.

The photograph and letters that I have read also point to a level of intimacy between these men. Shaw joined with some of the men above as messmates, a topic that is brilliantly explored by historian James J. Broomall in connection to Confederate soldiers:

A soldier’s messmates formed the center of an extended military family from which men drew strength by replicating their distant homes in military camps. (pp. 49-50)

Shaw and his closest friends shared extended periods of time together between campaigns. They shared letters from their respective families, recited poetry, and read literature to one another. Here is one of those moments described by Shaw in November 1861.

We have had a cold, rainy, and intensely uncomfortable day, but I have a nice little stone fireplace in my tent, with a pretty high chimney outside, which make it draw finely, and keep the tent warm and dry. In this camp, mine happens to be one of the successful fireplaces (they often smoke), so that I have had company all day. We have been, from reveille until tattoo, talking and reading, and having quite a nice time. Stephen Perkins, Rufus Choate, and Captain Savage were the guests. The latter is one of the best men I have ever known, and, at the same time, he is one of the best officers, and a real brave fellow. One of the rarest articles to be found is a pure-minded man, and Savage is as much so as any woman.

This was about more than simply finding ways to occupy themselves. Shaw and his comrades were attempting to recreate their cultural world in the middle of an encampment. There conversations and reading material reflected a broader view of the world that reinforced their sense of themselves as elites and what it was that they were fighting for.

Many of these same men gathered for their first Thanksgiving away from home. The men pooled their packages of cakes and other food items to round out their dinner.

Besides all the turkey and geese, they had nearly twelve hundred pounds of plum-pudding. The officers dinner was at 5 o’clock, and we enjoyed ourselves very much. Our mess-tent was gorgeously lighted with candles, bayonets serving for candlesticks, and the dinner was excellent. (November 23, 1861)

Thanksgiving dinner one year later, however, looked very different.

Yesterday was Thanksgiving, and we managed to have a very pleasant day. There would have been no drawback, if we hadn’t missed from the table so many faces which were last year at this time. This made the dinner a very quiet affair compared with most bachelor parties. Besides the seven officers killed last summer and this autumn, there are a good many at home wounded and ill; so that the society is materially changed since we came out. It is very strange and unfortunate, that the officers that have been killed were the very best we had, both as comrades and as military men. No doubt, after a man is dead his virtues only are remembered, but in our case the dead ones really were the best. (November 28, 1862)

Many of Shaw’s closest friends had been killed or seriously wounded at Cedar Mountain and Antietam. Shaw personally helped to prepare the bodies of four fellow officers after the fighting at Cedar Mountain and “had them packed in charcoal to go to Washington, where they” were “put in metallic coffins.” He took a lock of hair from each individual to share with their family and friends.

The loss of so many friends in such a short period of time was, to say the least, unsettling. His close-knit circle of friends had gradually diminished leaving him with fewer people to discuss subjects ranging from the changing scope of the war, including emancipation to whether he should accept new opportunities outside of the regiment.

As 1862 came to a close, Shaw was still serving in the Second.

“A man is or should be very loath to leave a regiment in which he has gone through as much as we have in this,” Shaw wrote to his sister Effie, “especially when it is such a one as ours.” “I have had a great many discontented moments, when I have thought I wanted to change, but when it came to deciding, I never went.” (November 21, 1862)

The bonds of comradeship and a shared experience exercised a good deal of influence on his decision to remain. That, of course, changed in early February 1863 when he was offered the colonelcy of the 54th Massachusetts.

Having read Shaw’s correspondence, I don’t think it is a stretch to characterize his hesitancy to accept the Governor John Andrew’s offer as a personal crisis. The death of so many close friends such as James Savage, who fell in battle at Cedar Mountain, left Shaw with fewer people to discuss what was an incredibly difficult decision. The remaining friendships, that were strengthened as a result of the hardships of camp life and especially battle, were difficult to sever in favor of a new command.

There is no question that his parents, especially his mother, were influencing factors as well, but there were plenty of moments before and during the war when they differed and Shaw held firm to his position.

Disappointing his parents or his fiancee was not the issue. Before any decision could be made, before Shaw could accept a new command that included so many unknowns, needed first to come to terms with the events of the previous nineteen months.

Very interesting, Kevin, and you share a valuable perspective on Shaw.

I look forward to the book, Kevin!