Robert E. Lee and the Return of the "Loyal Slave" to West Point

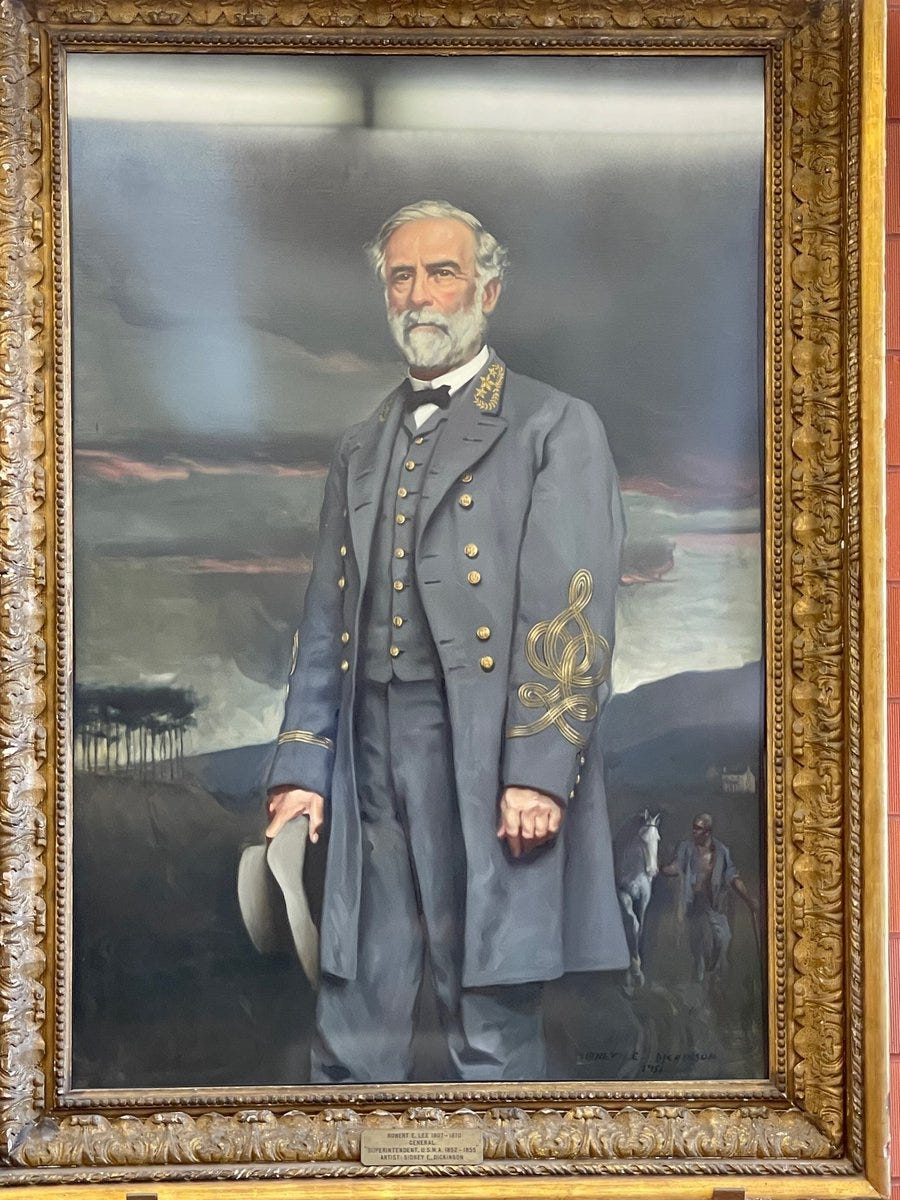

This week we finally got visual confirmation of the return of a portrait of Robert E. Lee to the Jefferson Library at West Point. It should come as no surprise that there was no ceremony to mark the painting’s return or apparently any other public notice from West Point.

While the emphasis has mostly centered on the Confederate general, I want to focus on the representation of the enslaved man in the background guiding Traveller, Lee’s trusted gray American Saddlebred, which he rode through much of the war.

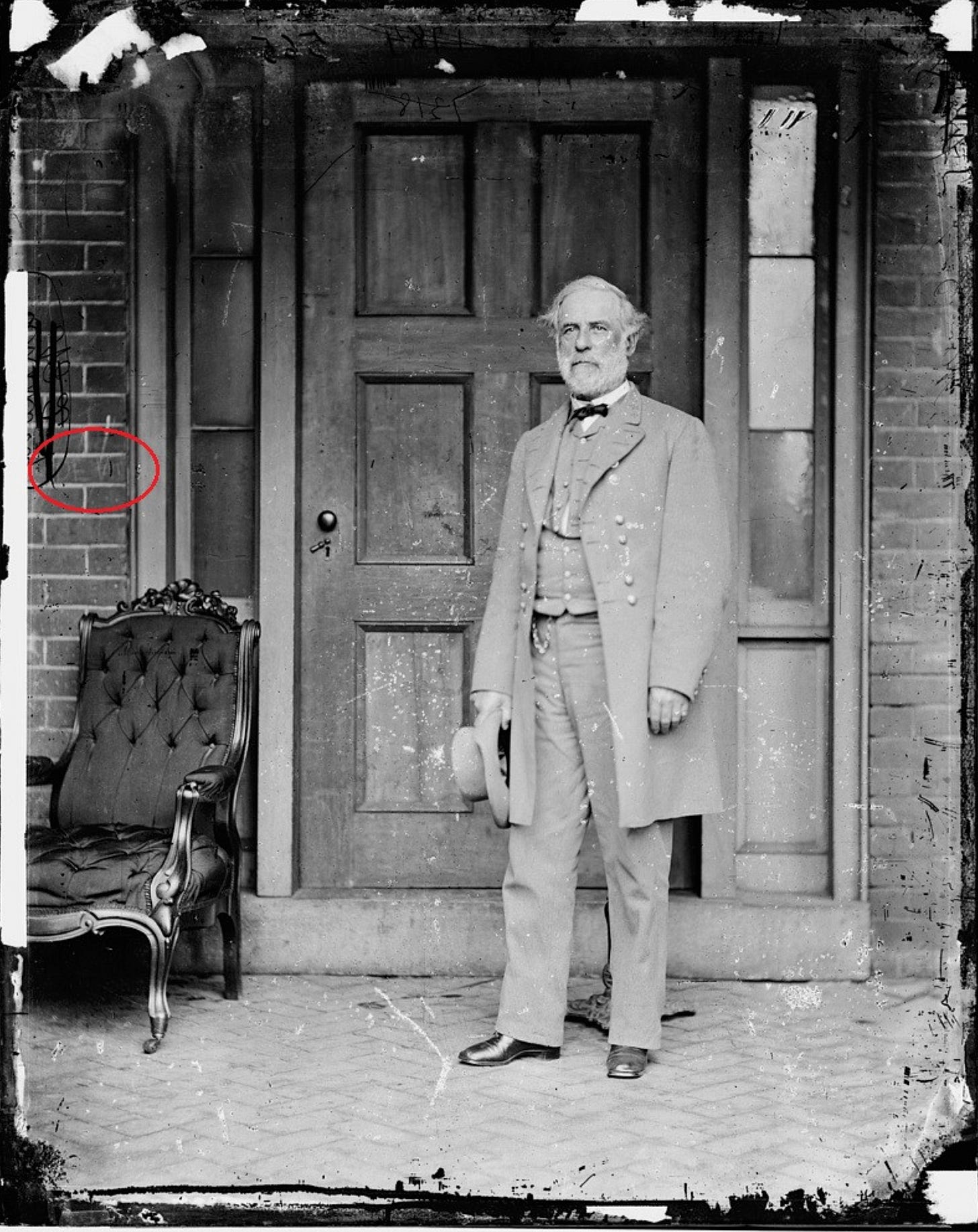

There are a number of ways to interpret the inclusion of this individual in the painting. Given that the painting is based on a a photograph of Lee, taken in Richmond, Virginia by Matthew Brady, on April 20, 1865, some people have suggested that the man is walking off in freedom.

As you can see, someone—likely a Union soldier—etched the word “devil” next to the entrance of the Lee family home.

As for the painting, which was completed in 1952, it is unlikely that the Black man depicted was intended to represent emancipation.

We could also interpret it as representing the extent to which Lee and the Confederate army relied on slave labor during the war. Indeed, Confederate armies relied on thousands of enslaved laborers to free up as many white soldiers as possible to carry a rifle. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia may have included upwards of 10,000 slaves when it crossed into the free state of Pennsylvania in late June 1863.

This is also unlikely.

What we are looking at is a representation of the Lost Cause narrative’s celebration of the “loyal slave.” Lost Cause authors, according to historian Chris Graham, “consistently described slavery as a benevolent institution in which white and black southerners engaged in a reciprocal relationship that secured a domestic peace that abolitionists threatened.”

As I demonstrate in my book Searching for Black Confederates this narrative was easily extended into the war as thousands of slaves accompanied their enslavers into the army as body servants or what I call “camp slaves.” These men performed vital functions in camp and on the march and came to their master's aid on the battlefield without question.

After the war, these men were welcomed to veterans reunions and monument dedications as representative of the “loyal slave”—a narrative that now made it possible for former Confederates to deny that their government’s sole purpose was the protection and expansion of slavery.

Stories and images of these men could be found in books and articles written by some of the South’s most popular writers as well as on numerous Confederate monuments dedicated at the turn of the twentieth century.

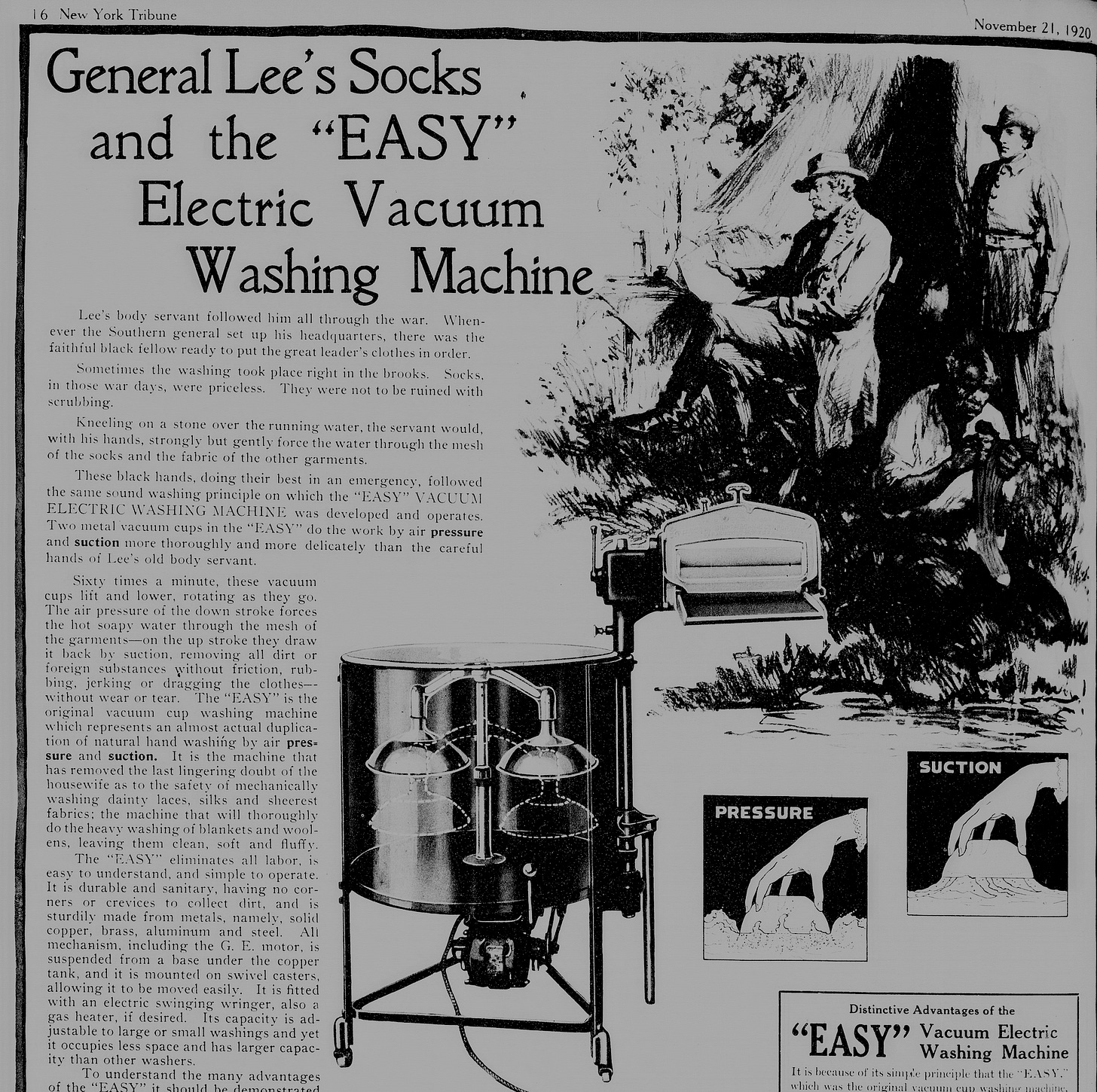

Even advertising agencies used the image of the “loyal slave” or body servant to sell various products. This one appeared in the pages of The New York Times in 1920

Both the image of Lee and the body servant in the pages of a major newspaper point to the widespread popularity and embrace of the Lost Cause narrative.

It should come as no surprise that African Americans might try to benefit or even profit from a close association with Confederate veterans and especially the memory of Robert E. Lee himself. As I document in my book, former body servants profited in numerous ways by playing the role of the “loyal slave” at various commemorative events. Some outright lied about their roles and connections to high-profile generals during the war.

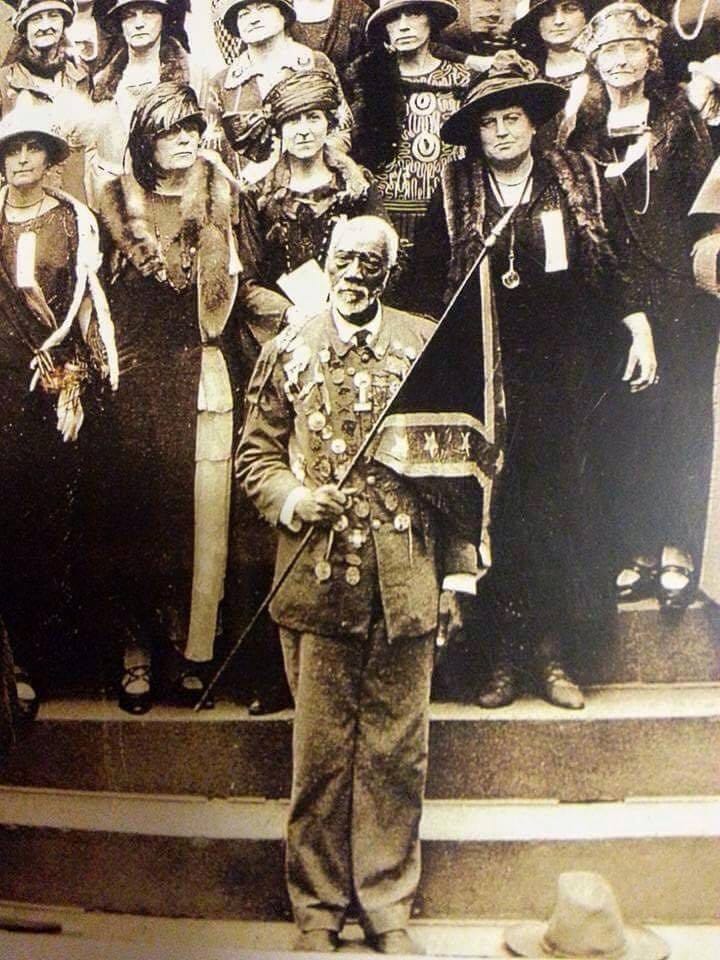

William Mack Lee is a case in point. Following his ordination as a Baptist Minister in Washington, D.C. in the 1880s, Mack Lee used reunions and other veterans' events to raise money for his church and congregation. He presented himself as a Lee family slave and as a “cook and servant” to none other than Robert E. Lee himself throughout the entire war. Mack Lee used every opportunity at reunions to raise money, including charging 50 cents for each photograph taken. He “sang his old plantation songs to appreciative audiences—so appreciative that they will stock his pantry for the coming winter.” Lee's popularity took him to the Georgia House of Representatives, where he addressed the body “wearing a coat of Confederate gray" and "declared his perfect faith in the white man of the South doing the right thing for his race.”

In 1918 Mack Lee published a biographical pamphlet that once again placed himself at the center of the war with General Lee. The pamphlet includes a number of historical inaccuracies. In addition to claiming to be a former Lee family slave, Mack Lee also placed himself with R. E. Lee at First Manassas in July 1861 and as a cook for Confederate generals “in de Wilerness” on July 3, 1863. In attendance were Stonewall Jackson and George Pickett as well as Lee. The pamphlet aligned Mack Lee with the central tenets of the "loyal slave" narrative: “The fact that the war had set him free was of small moment to him, and he stayed with his old master until his death”—again, stressing the theme that Mack Lee's devotion and service was not to the state or nation, but to his owner, personally.

What proved problematic for Mack Lee was not anything factual in his account; indeed, almost nothing in his pamphlet can be verified and it is unlikely that he was anywhere near a Confederate camp during the war. Rather, it was the claim that he and R.E. Lee were “real friends” and that the general confided in Mack Lee that attracted concern.

In 1927 the editor of Confederate Veteran magazine, E.D. Pope, offered a direct response to the claims made by Mack Lee under the heading, "More Historical “Bunk.’” “The ridiculousness of the claim to have been a ‘real friend’ of General Lee,” argued Pope, “is only equaled by the absurdity of the stories told by the old negro.” He went on to suggest that, “If General Lee ever made a confidant of anyone with whom he was associated it is not known, and much less he would have revealed himself to a negro servant.”

Historical slights and exaggerations could be tolerated, but the relationship depicted by Mack Lee with the great Confederate chieftain went too far and directly challenged the racial hierarchy of the postwar South.

As I recall, somewhere around fifteen Black men claimed to have been Lee’s body servant during the war. I still possess a large file of emails from people, who have written me over the years that there ancestor was Lee’s body servant.

Even after having been revealed to be a fraud by real Confederates, neo-Confederates, including the Sons of Confederate Veterans, continue to embrace Mack Lee as one of their own, going as far as to dedicate a headstone in his honor.

An understanding of real history has never been their strong suit.

The return of the portrait of Robert E. Lee to West Point is an insult to every Black American, who has served or will serve this nation.

At a time when the Trump administration is actively suppressing the work of public historians and the history of American slavery, the decision to highlight one of the most harmful historical myths in American history should be roundly condemned by all of us.

The story of “faithful bondsmen” cries out for treatment by novelists.

With Trumps efforts to change how the Smithsonian portrays slavery, it's almost as if the portrait says do it this way.