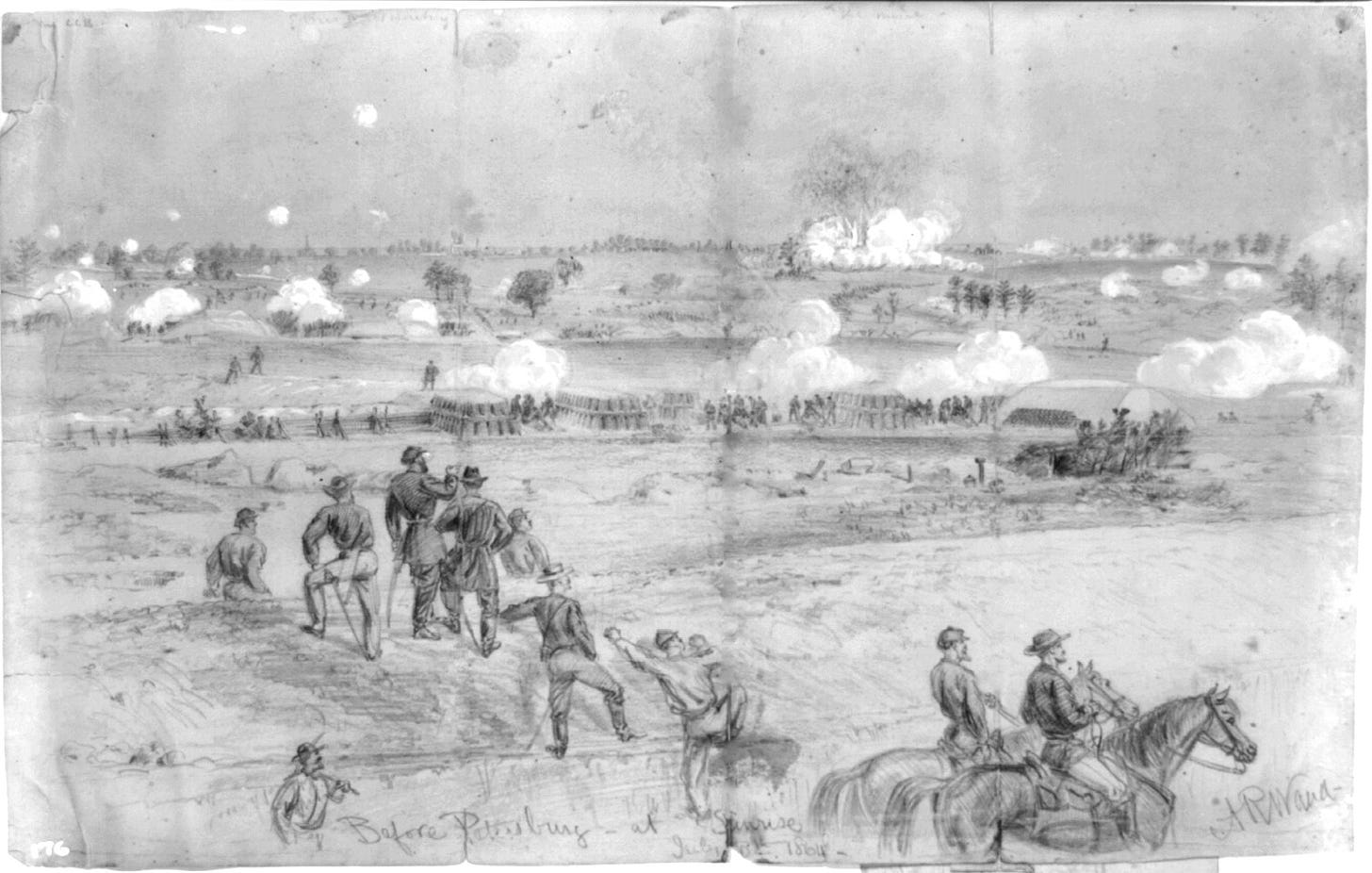

On this day in 1864, Major General Ambrose Burnside’s Ninth Corps detonated 8,000 pounds of gunpowder under a Confederate salient outside Petersburg, Virginia. The ensuing battle and eventual Confederate victory became known as the battle of the Crater.

In addition to the massive explosion that preceded the assault, the battle is also known for the presence of an entire division of United States Colored Troops. This was the first time in the War in the East that Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia faced off against a large number of African Americans. Upwards of 200 of these men were executed by Confederates both during and especially after the battle.

The battle was the subject of my first book, Remembering the Battle of the Crater: War as Murder (University Press of Kentucky, 2012), which focused specifically on how the racial aspect of this battle was remembered.

Here are a few facts about the battle that you may not be aware of, all of which are explored in my book.

The mine that was constructed by the men in the 48th Pennsylvania eventually measured 511 feet. The entrance that you see today is not the original entrance, but was constructed by the National Park Service. The original mine entrance was located further back.

There is no evidence that the Fourth Division of United States Colored Troops engaged in any specialized training before the assault. Such claims have been used to suggest that if they had been utilized in the first wave, the assault would have been successsful.

Most of the United States soldiers were able to avoid the crater itself to occupy a complex chain of traverses and entrenchments in the Confederate line.

Though the massacre of Black soldiers by Confederates is well documented, there is evidence that USCTs also executed Confederates who tried to surrender. These incidents offer different perspectives on the battle. I explore this subject in a collection of essays titled, From Cold Harbor to the Crater, edited by Gary Gallagher and Caroline Janney.

Captured Black soldiers who were not executed were either sent to Confederate prisons or claimed by local slaveowners.

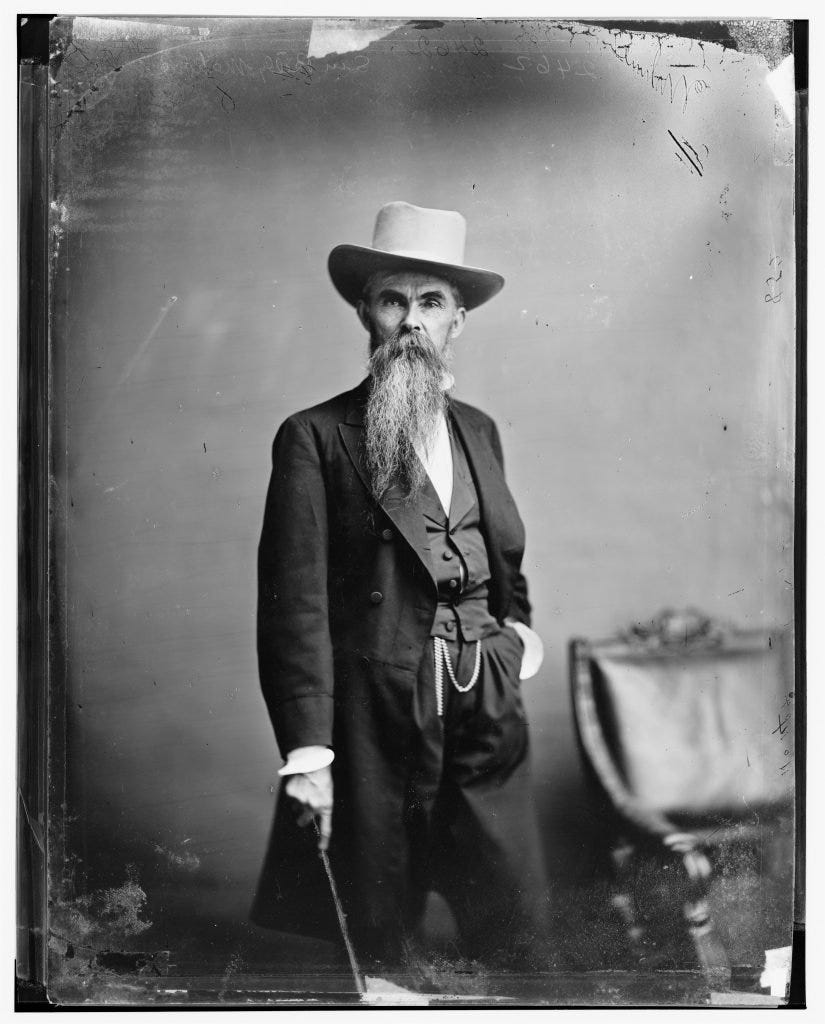

Confederate general William Mahone, who led the counterattack that resulted in the retaking of the Crater and securing victory that day, went on after the war to consolidate a numbrer of railroad lines. Later he led one of the most successful bi-racial third parties in history called the Readjusters. Between 1879 and 1883 Readjusters controlled Virginia state government. African Americans voted in large numbers and served in elected office at every level throughout the Commonwealth.

For a few years in the 1920s, the Crater battlefield was part of an 18-hole golf course. Tourists were still given access to what was left of the crater itself.

Historian Douglas Southall Freeman attended the 1903 Crater reenactment with his father and credited the event with sparking his interest in Civil War history. Freeman later provided live commentary for a large crowd who attended the 1937 reenactment on the battlefield in Petersburg.

When Black high school and college students challenged segregation in Petersburg in the 1960s they chose to do so at the public library, which was then located in William Mahone’s former home. A student touched off the protest by requesting a copy of Douglas Southall Freeman’s Pulitzer-Prize winning biography of Robert E. Lee.

It’s a fascinating story. As always, thanks for reading. Have a great weekend.

As always, Kevin, thoughtful and fascinating. Thank you!

Being retired now, I often lose track of the calendar, so I had no idea it was the 30th. I had forgotten that you pointed out that the existing mine entrance is not the actual one. Most studies of the Crater that I read in my distant past focused on the building of the mine, and did not do a very good job of discussing the evolution of the battle itself. And the classic studies of the fight give not even a hint of the executions of USCTs (that I recall). And I had no idea of Mahone's interesting postwar career until I read your book.