Remembering and Forgetting Violence in Nat Turner's Virginia

People have strong views when it comes to Nat Turner.

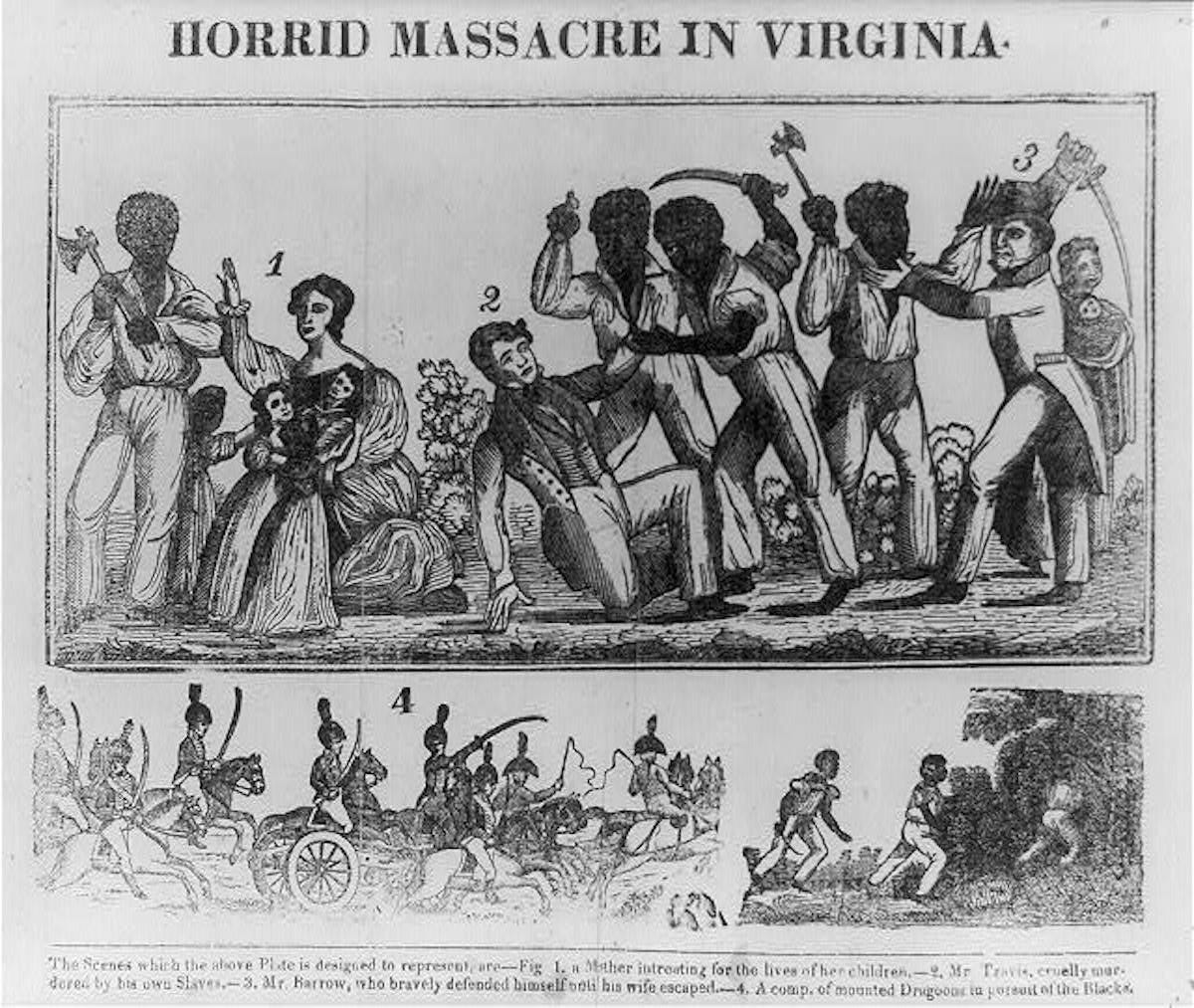

On August 22, 1831, Nat Turner led a group of enslaved people through Southampton County, Virginia in what proved to be the largest slave rebellion in American history. Over the course of two days, Turner and his band of followers killed over fifty white men, women, and children, sometimes in a brutal manner.

White Virginians managed to put down the rebellion and exacted revenge on the enslaved population through trials and executions. Turner escaped initial capture, but was eventually captured and executed a few months later, but not before doing numerous interviews, including one with lawyer Thomas Gray. His Confessions of Nat Turner—a supposed transcription of his interview with Turner—is the closest we can get to his own words and motivation for what transpired.

There is no question that Turner embraced violence as a means to free himself and the local slave population. How we evaluate his actions today, close to two hundred years later, can still elicit strong emotions and judgements. Quite often, however, these responses tell us more about how we choose to remember the past and the conditions under which violence is not only permissible, but how it impacts us personally all these years later.

I was reminded of this as I was reading a blog post at one of my favorite Civil War websites. The post was a review of a new book about Nat Turner that was started by historian Anthony Kaye and completed by Greg Downs after the former’s passing. I’ve only had a chance to read the introduction and a few sections, but it looks to be well worth reading.

It was the comments following the blog post, however, that caught my attention.

As one who grew up in Franklin/Southampton County, I have no difficulty understanding his murder of unarmed men, women and children asleep in their beds was a crime and not an act of war. Him being bat shit crazy doesn’t change that fact.

What Nat Turner did is no different than the attacks last October on Israel by Hamas. Targeting women and children is morally depraved. Terrorism for a “moral” cause is still terrorism.

Any examination of Nat Turner’s life reveals that he was a paranoid schizophrenic who became homicidal.

There is nothing special about these particular comments. It’s all too common when responding to Turner and even John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

The point here is not to defend or condemn Turner.

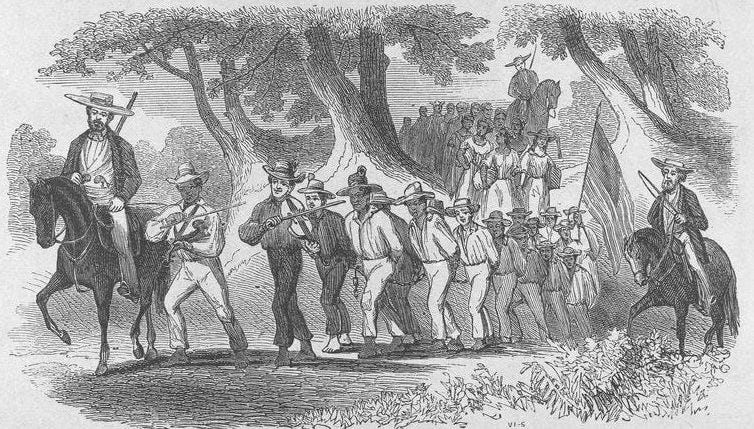

What I find fascinating is the apparent unwillingness and failure to place the violence and hatred that animated Turner and his followers within a broader historical context. Slave rebellions took place regularly throughout the broader Atlantic World at the end of the eighteenth and through the first few decades of the nineteenth century in places like Saint Domingue, Demerera, and Barbados. A few months after Turner’s Rebellion a much larger insurrection in Jamaica (“Baptist War”) involving 60,000 slaves broke out.

A slave rebellion near New Orleans in 1811 and the arrest of leaders like Gabriel in Richmond and Denmark Vesey in Charleston were easily recalled by white Southerners in 1831, who were in constant fear of slave rebellions—both real and imagined. They followed the news closely from around the region.

It’s interesting that, in contrast with Turner, we don’t have the same visceral reactions to the leaders of these and other slave rebellions. No accusations of anyone being “bat shit crazy” or “homicidal.”

And then there are the enslavers themselves. For some reason they fail to elicit the same type of responses that Turner attracts. Sure, we might admit that slavery was immoral, but where is the disgust and anger in response to the horrific forms of violence (both physical and psychological) that was enacted each and every day for hundreds of years in order to maintain the institution of slavery? Why am I doubtful that the above writers have never once referred to a slaveowner as “bat shit crazy” or “homicidal.” Is it because slavery was legal or because it was considered a “way of life”?

This gets back to my initial point that we have a responsibility as students of history to place Turner’s violent rebellion within a broader system and culture that sanctioned horrific violence that was meted out to men, women, and children on a daily basis.

What troubles me most about the kinds of accusations made against Turner is that they echo the arguments made by enslavers in the wake of Turner’s rebellion. Accusing Turner of being a “paranoid schizophrenic” undercuts any argument against slavery. As Kaye (and Downs) point out: “If a fanatic sparked the rebellion, then the rebellion was no indictment of slavery or even of the specific enslavers in the Cross Keys neighborhood; the rebellion was solely the product of an insane mind.” (p. xv)

Thanks to all of you who tuned in to my most recent Substack live discussion. This will be the last live chat open to all subscribers. You will need to upgrade to a paid subscription to continue to receive notifications. I’ve received very positive feedback thus far and I am excited to continue our discussions. In addition to upgrading…

…make sure to download the app to your iPhone or Android.

There is no evidence that Turner was insane. One aspect of this new book about Turner that is particularly helpful is the authors’ exploration of Turner as a “particular kind of [Methodist] prophet.”

This Methodist surge was part of a disruption in the colonies in the late eighteenth century that created openings for prophets claiming direct revelation from God. Responding to the political transformations of the colonial Revolution against Britain and the religious upheavals of the subsequent Second Great Awakening, Baptists, Methodists, and other sects grew too dramatically to be forced into any sort of sanctioned form. Many white and Black prophets claimed to have received commands from God, some couched in the common evangelical language of warfare. Many prophets like Nat, Methodist, a denomination with a particularly strong fixation on the imagery of religious warfare. In this era, unaffiliated prophets like Joseph Smith and Robert Matthews, both influenced by Methodism, claimed to found entirely new branches of Christianity, while the former Baptist William Miller became convinced he had discovered the precise date of Christ’s Second Coming and thus of the apocalyptic warfare to follow. (p. xvii-xviii)

I appreciate this deep historical context because it helps us to better understand how broader religious and cultural forces shaped his outlook and helped to frame his own role in in trying to bring an end to slavery. This is even more important in light of the amount and nature of historical sources about Turner.

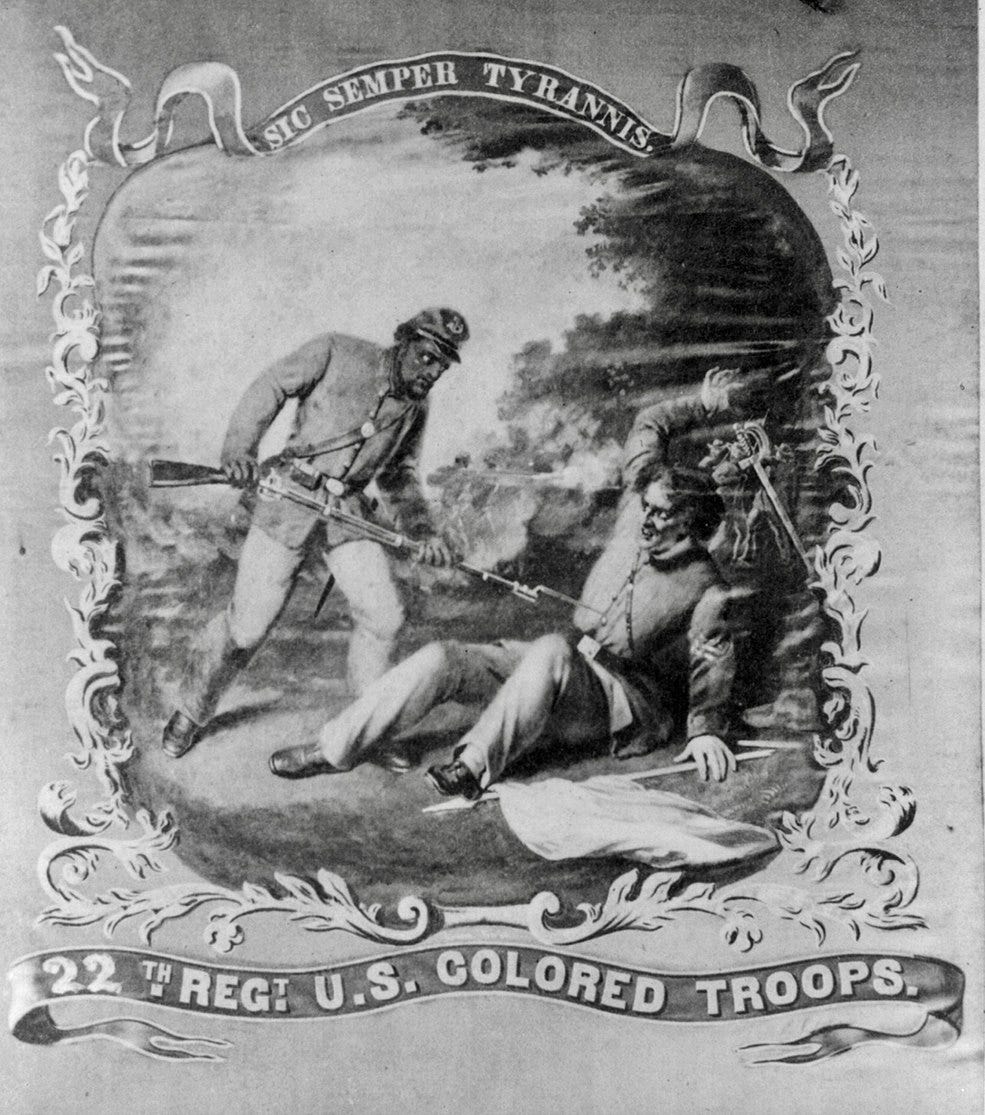

Roughly thirty years later thousands of formerly enslaved men took up arms to defeat the Confederacy and end slavery. Many of these regiments sang songs like “John Brown’s Body” as they marched through the plantations on which they and their families were once shackled and tortured. (See Christian McWhirter’s book Battle Hymns.)

Confederates viewed these men as engaged in a slave uprising. From a certain perspective, they were. It is likely that many of the Black soldiers from Southampton County, Virginia and the surrounding area found strength in the stories they heard about another warrior, who once fought for freedom.

In the broader context, I always think of the story of Denmark Vesey in Charleston, of whom I imagine Nat Turner was somewhat aware. Denmark, who had purchased his freedom, just happened to be a member of the AME church which would become the current-day "Mother Emanuel," where nine people in a Bible study were murdered by Dylann Roof in 2015.

But in terms of the obvious longstanding failure to realistically consider the perspective of what it was like to be enslaved and its effects on the psyche and the "accepted" belief system that made any slave "uprising" a result of "bad" men, I think forward to the case of Trayvon Martin just a few years ago.

I confess that I don't have any idea what was said or not said in the courtroom, but knowing that the "stand your ground" defense in Florida was used for George Zimmerman, an "upstanding" gentleman in his neighborhood who was later accused of domestic violence by a partner, I remember wondering why the prosecution apparently failed to point out that 17-year-old Trayvon was entitled to "stand his ground" first. I would think the fact that his father was a resident in the neighborhood, entitled to his "ground," meant that the same rights to that ground would have passed to his child. But no. Trayvon, a 17-year-old boy who happened to be Black and wearing a hoodie on his way home with candy from a convenience store, had no right to defend himself first apparently. In my mind, George Zimmerman violated Trayvon Martin's ground and when Trayvon responded, he shot and killed him. Zimmerman lost his right to "stand his ground" the moment he ignored the advice of the police who told him to stay home.

I won't pretend that I believe violence is ever excusable except in clear cases of self-defense. And I won't pretend that if you attack someone I love that I won't respond with violence. I can't speak to the moral fiber or mental illness of Nat Turner or Denmark Vesey, but I do understand that there comes a time when desperation turns into violence. And 400 years of feet on the necks of African human beings and their progeny forced to labor in intolerable circumstances and live in squalor under threat of death to fill the pockets of their "masters" is far more than enough to break the camel's back.

I'm going to forward this to Brian Rose. He's working on a photo project related to this topic. He is the author of "Monument Avenue." I see he's using a quote you gave him for that book! https://www.brianrose.com/monument.htm