Remembering and Forgetting in Gettysburg

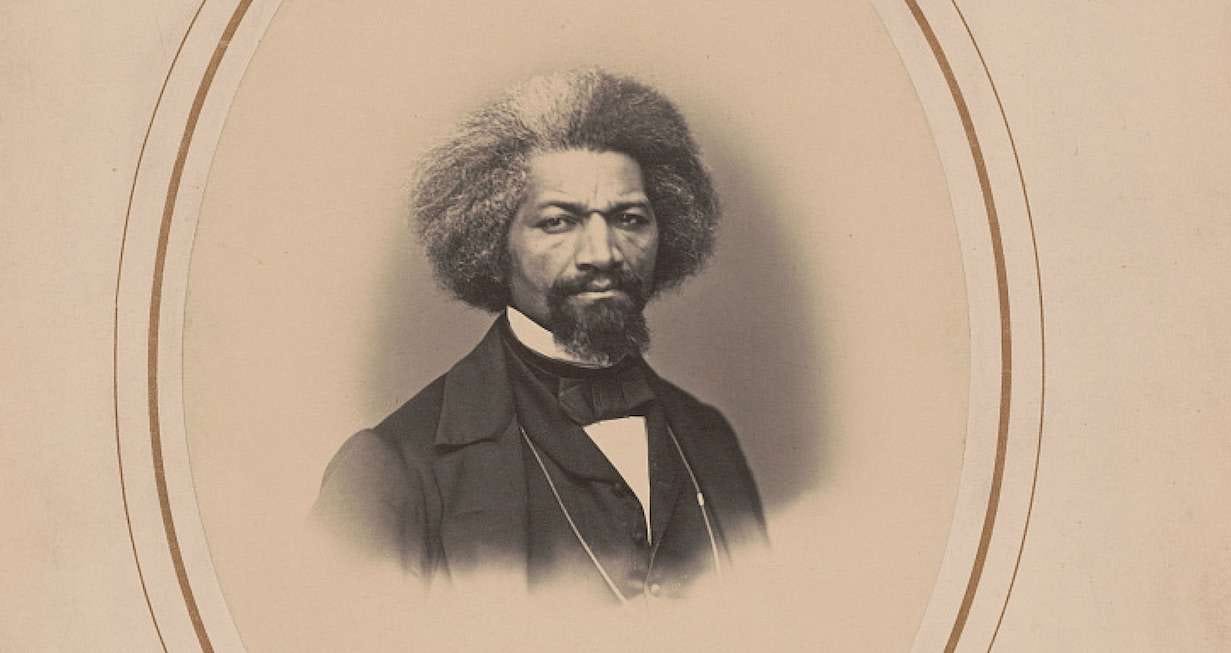

Frederick Douglass was unambiguous about the moral stakes of the American Civil War. To him, the conflict was not simply a dispute over federal authority or regional economic differences; it was a battle between a nation striving toward justice and a nation, whose “cornerstone” was rooted in profound moral evil. In his speeches, essays, and letters, Douglass repeatedly framed the war as a struggle between freedom and slavery, right and wrong, and ultimately democracy and tyranny.

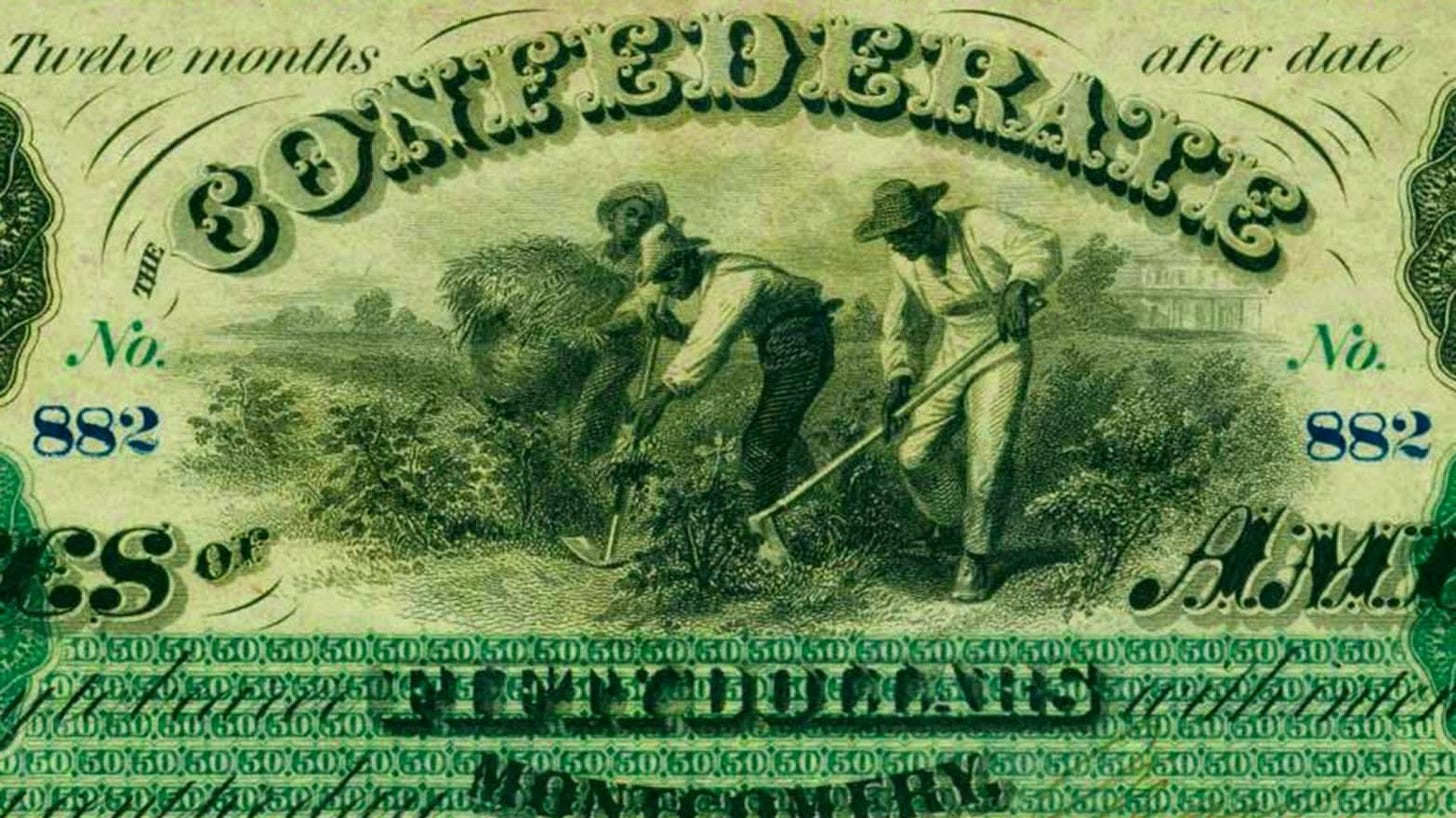

Douglass insisted that the Civil War was fundamentally a war about slavery. While many politicians initially attempted to portray the conflict as a fight to preserve the Union alone, Douglass believed such explanations evaded the central truth. The Confederacy was founded to protect and expand human bondage. For Douglass, this made the Confederacy undeniably wrong in moral, political, and spiritual terms.

He frequently quoted Confederate leaders’ own words as proof. In analyzing Vice President Alexander H. Stephens’s “Cornerstone Speech,” which explicitly stated that the Confederacy rested upon the idea that “the Negro is not equal to the white man,” Douglass argued that the South itself had declared the cause of the war to be slavery. Thus, he asserted, no one could claim the conflict was morally vague.

Douglass considered the United States the side of “right,” but his support came with criticism. The United States, he said, had tolerated slavery for too long and entered the war reluctantly, without a clear antislavery purpose. Early in the conflict, he chastised President Abraham Lincoln for hesitating to make the war explicitly about emancipation.

Yet Douglass also believed the United States held within it the promise of the nation’s founding ideals. He argued that the Declaration of Independence—though betrayed by slavery—contained principles of liberty that the Union could still redeem. When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Douglass declared that the war had at last become “a moral crusade for human freedom,” and he enthusiastically supported the Union cause.

Douglass maintained that the enslaved themselves were not passive victims in this struggle. They were central actors in deciding the war’s outcome. He urged formerly enslaved men to enlist in the United States Army, arguing that Black participation would prove their manhood, claim their citizenship, and help ensure that victory brought genuine liberation. When Black regiments finally fought, including the 54th Massachusetts, Douglass saw this as confirmation that justice and courage were on the side of freedom.

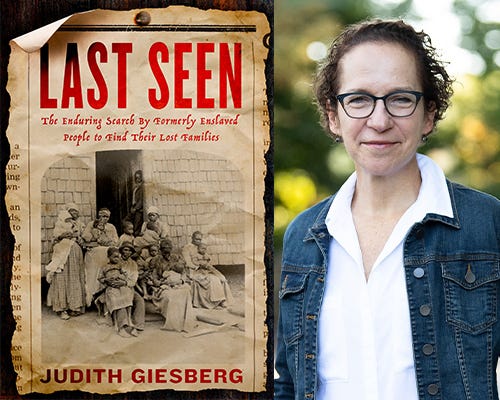

Join the Civil War Memory Book Group

Our next meeting will take place on January 11, 2026 at 8PM EST. We will meet to discuss Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families by Judith Giesberg.

Note: The book group is open to PAID SUBSCRIBERS ONLY. Upgrade now to join.

Throughout his public writings, he emphasized that enslaved people fleeing plantations, supplying intelligence, and joining the Union cause made the Confederacy’s defeat possible. This, he argued, demonstrated that history itself aligned morally with the Union, not the slaveholding South.

When the Union prevailed, Douglass saw the outcome as a vindication of the side of right. He believed the Civil War had answered definitively the questions of who was right and who was wrong. The United States had fought, however imperfectly, for human freedom, while the Confederacy had fought for the perpetuation of slavery. “No war was ever more just,” Douglass said, because it destroyed the institution that contradicted the nation’s founding principles.

Douglass offered the following observation during an 1878 Memorial Day address:

Nevertheless, we must not be asked to say that the South was right in the rebellion, or to say the North was wrong. We must not be asked to put no difference between those who fought for the Union and those who fought against it, or between loyalty and treason…

But the sectional character of this war was merely accidental and its least significant feature. It was a war of ideas, a battle of principles and ideas which united one section and divided the other; a war between the old and new, slavery and freedom, barbarism and civilization; between a government based upon the broadest and grandest declaration of human rights the world ever heard or read, and another pretended government, based upon an open, bold and shocking denial of all rights, except the right of the strongest.

Good, wise, and generous men at the North, is power and out of power, for whose good intentions and patriotism we must all have the highest respect, doubt the wisdom of observing this memorial day, and would have us forget and forgive, strew flowers alike and lovingly, on rebel and on loyal graves. This sentiment is noble and generous, worthy of all honor as such; but it is only a sentiment after all, and must submit to its own rational limitations. There was a right side and a wrong side in the late war, which no sentiment ought to cause us to forget, and while today we should have malice toward none, and charity toward all, it is no part of our duty to confound right with wrong, or loyalty with treason. If the observance of this memorial days has any apology, office, or significance, it is derived from the moral character of this war, from the far-reaching, unchangeable and eternal principles in dispute, and for which our sons and brothers encountered hardship, danger, and death….

… though freedom of speech and of the ballot have for the present fallen before the shot-guns of the South, and, the party of slavery is now in the ascendant, we need bate no jot of heart or hope. The American people will, in any great emergency, be true to themselves. The heart of the nation is still sound and strong, and as in the past, so in the future, patriotic millions, with able captains to lead them, will stand as a wall of fire around the Republic, and in the end see Liberty, Equality, and Justice triumphant.

I thought about Frederick Douglass and this speech as I watched the livestream of Gettysburg’s annual Remembrance Day parade this weekend, which commemorates Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.”

It’s a festive occasion. Local residents and visitors line the streets as white and Black Union reenactors march passed. In recent years, I’ve waited patiently for the Confederate reenactors to appear, along with Gettysburg College historian Scott Hancock and his trusted sign.

Scott appears at the 45:00 minute mark.

I like to think that Scott is channeling Douglass for the benefit of the crowds gathered, who would likely prefer to ignore such uncomfortable thoughts. But this army not only “fought for slavery.” While in Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863, the army kidnapped hundreds of free Black residents and forced them south to depots for sale into slaveery.

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was a slave-catching army.

It's Time To Push Out Confederates From Gettysburg For Good

Imagine if one of the first things we acknowledged about the Confederate army, when it entered Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863, is that it included thousands of enslaved men. It would change how we think about the campaign, its outcome, and its place in the broader trajectory of the war.

Scott’s personal crusade is even more important this year as African-American history—specifically the history and legacy of slavery and race—remains under assault by the Trump administration both here and abroad.

Now more than ever, as we approach the 250th anniversary of this nation’s birth, all of us need to find ways to channel the courage and defiance of Frederick Douglass and stand up for truth in history and memory.

Douglass's insistance that we not confound right with wrong feels particuarly relevant when watching Confderate reenactors march in commemoration of Lincoln's address. The fact that Lee's army actively kidnapped free Black Pennsylvanians adds a layer that many visitors probably never consider when they watch these parades.

Just wondering, to what extent were enslaved people part of, or used to support, the state militia and forces in the South during the American Revolution?