The final chapter of my biography of Robert Gould Shaw explores how he was remembered and commemorated in the years after the Civil War. It is not an exhaustive survey of Civil War memory surrounding Shaw. The chapter ends with the dedication of the Shaw/Fifty-fourth Massachusetts memorial in Boston in 1897 and is followed by a short epilogue to close things out.

Much of the chapter is centered around Rob’s mother, Sarah Blake Shaw, who worked tirelessly to help shape and defend his legacy.

One of the many ways that Shaw was remembered throughout this period was through mass produced illustrations/lithographs. Here is a brief overview of some things I’ve been thinking about.

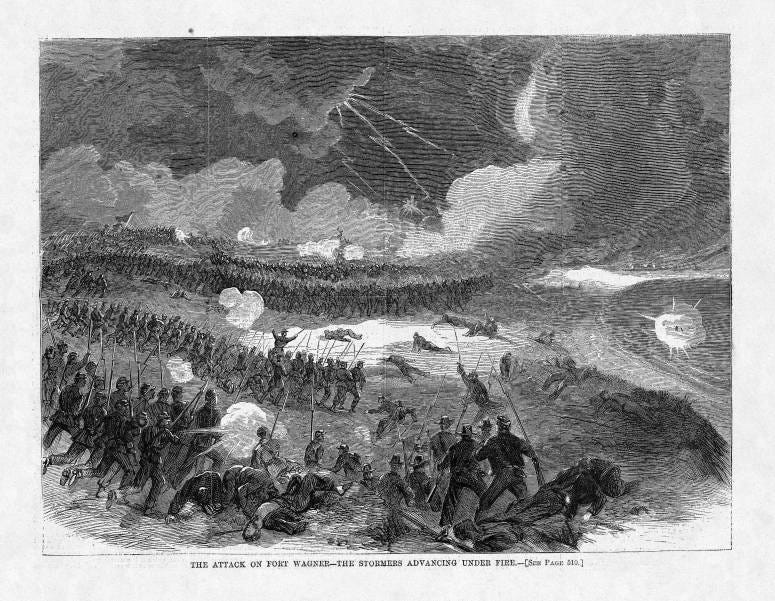

A number of pictorial representations of the assault on Fort Wagner appeared shortly after Shaw’s death beginning with Harper’s Weekly’s depiction of the assault, which appeared in its pages on August 8, 1863. The perspective of the illustrator from the rear of the assault, suggests that the nation’s attention had yet to focus on the charge of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts.

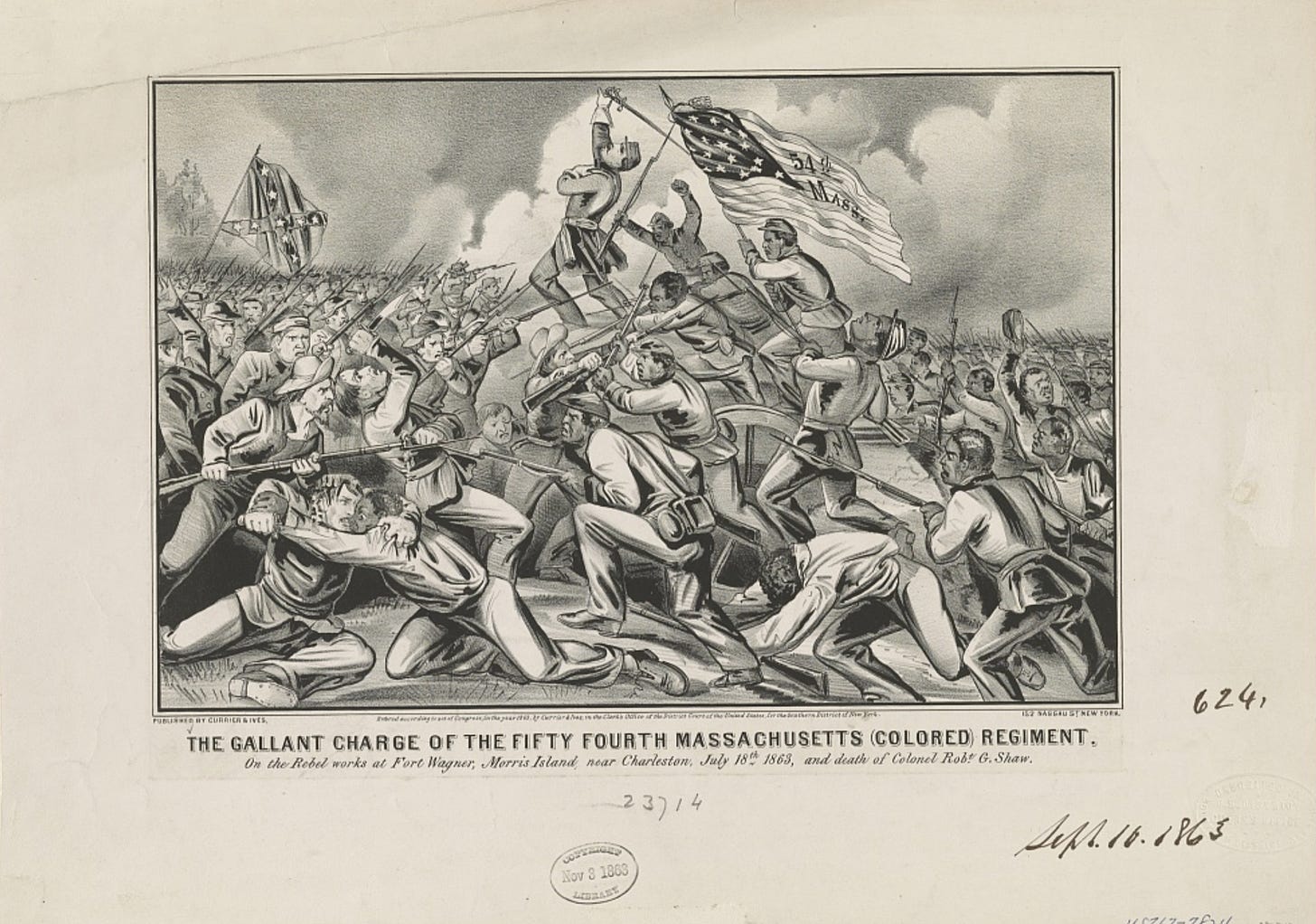

Shortly thereafter, “The Gallant Charge of the 54th Massachusetts (Colored) Regiment,” from Currier & Ives was released with its focus on Shaw and the national flag at center surrounded by his men and poised to breach Fort Wagner’s defensive walls. This served as the foundation for future prints.

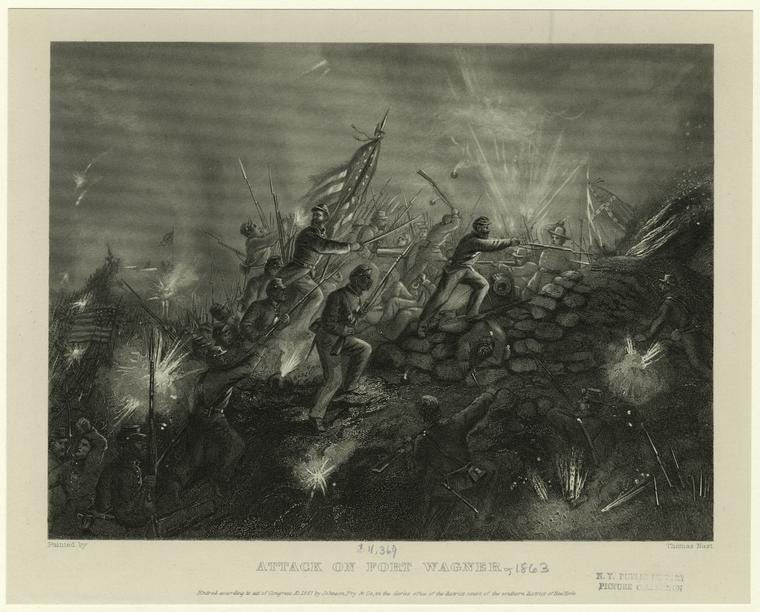

In 1867, the illustrator Thomas Nast produced “Attack on Fort Wagner” for Evert A. Duyckinck’s National History of the War for the Union Civil, Military, and Naval. Though Shaw is depicted inaccurately with sideburns, the print accurately highlights the confusion of night time fighting and close hand-to-hand combat.

For Nast, this wartime scene fit into a larger body of work that “emphasized freedmen’s potential in American life” and reminded the American people of the wartime sacrifices that justified the rights and privileges of full citizenship for African Americans.

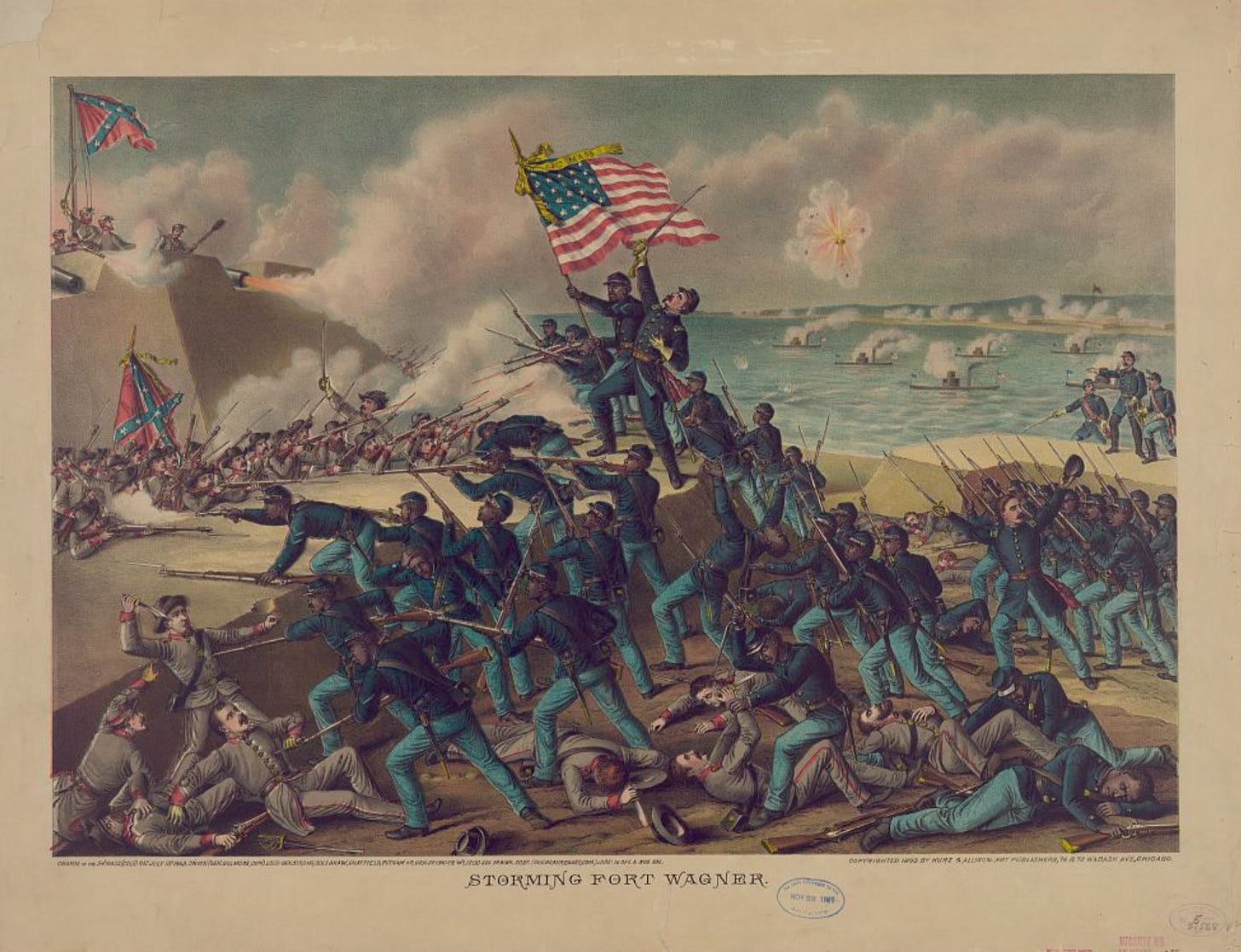

In 1890, the Chicago-based print maker Kurz & Allison released the colored lithograph “Storming Fort Wagner.” The choice to inaccurately depict the assault on Fort Wagner as taking place in full daylight allowed the illustrator to more clearly depict details such as soldiers wrestling one another to the ground and Black soldiers plunging their bayonets into the chests of Confederate soldiers.

Like the Currier & Ives print, Kurz & Allison feature Shaw at the center of the action, sword unsheathed, leading his men into the fort at the very moment he is shot. William Carney stands defiantly next to him holding the national flag.

The racialized nature of the fighting is vividly portrayed as it would be again, even more dramatically, with the release of The Fort Pillow Massacre in 1892. The scene centers on the Confederate massacre of United States Colored Troops and defenseless Black civilians at Fort Pillow, Tennessee on April 12, 1864. It should be noted that there is little evidence that Black civilians were massacred.

The attention focused on Shaw in these mass produced prints, however, did not always explain their popularity, especially among African Americans. The Richmond Planet, a Black newspaper founded by John Mitchell Jr. in 1883 offered the Kurz & Allison print to its readers.

A small number of Black Virginians had served in the Fifty-fourth and Black soldiers had liberated the seat of the Confederate government in early April 1865 after it had been abandoned.

Mitchell likely anticipated sales based on an interest in the depiction of Black soldiers and Carney rather than Shaw and marketed the print accordingly. “[H]ere is where the 54th Massachusetts regiment won undying fame. Colonel Carney is on the breast-works waving the flag of the union. Look at the Confederates. They pour shot into the colored troops. The rebel flag waves from the breast-works. Cannon belch forth their deadly contents. The colored troops do not falter.”

The misidentification of Carney as a colonel renders Shaw’s absence that much more conspicuous, but also speaks to racial pride among African Americans and an intense focus on Black soldiers at a time when their place in the nation’s Civil War memory was gradually receding.

For Black Richmonders specifically, the memory of emancipation and Black military service was quickly being overshadowed by the dedication of Confederate monuments throughout the city, including one honoring Robert E. Lee in 1890.

This is a fine conclusion, and the illustrations will reinforce your argument. Looking forward to this book.

Thanks for posting this. It would have been interesting to me anyway, but it was all the more interesting because I once heard David Blight telling how moving he finds the Boston memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that you mention in the first paragraph.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/47/Robert_Gould_Shaw_Memorial_%2836053%29.jpg