Correction: The article is referring to the state-developed course on African American history and not the AP course. Thanks to my friends at New American History for the correction.

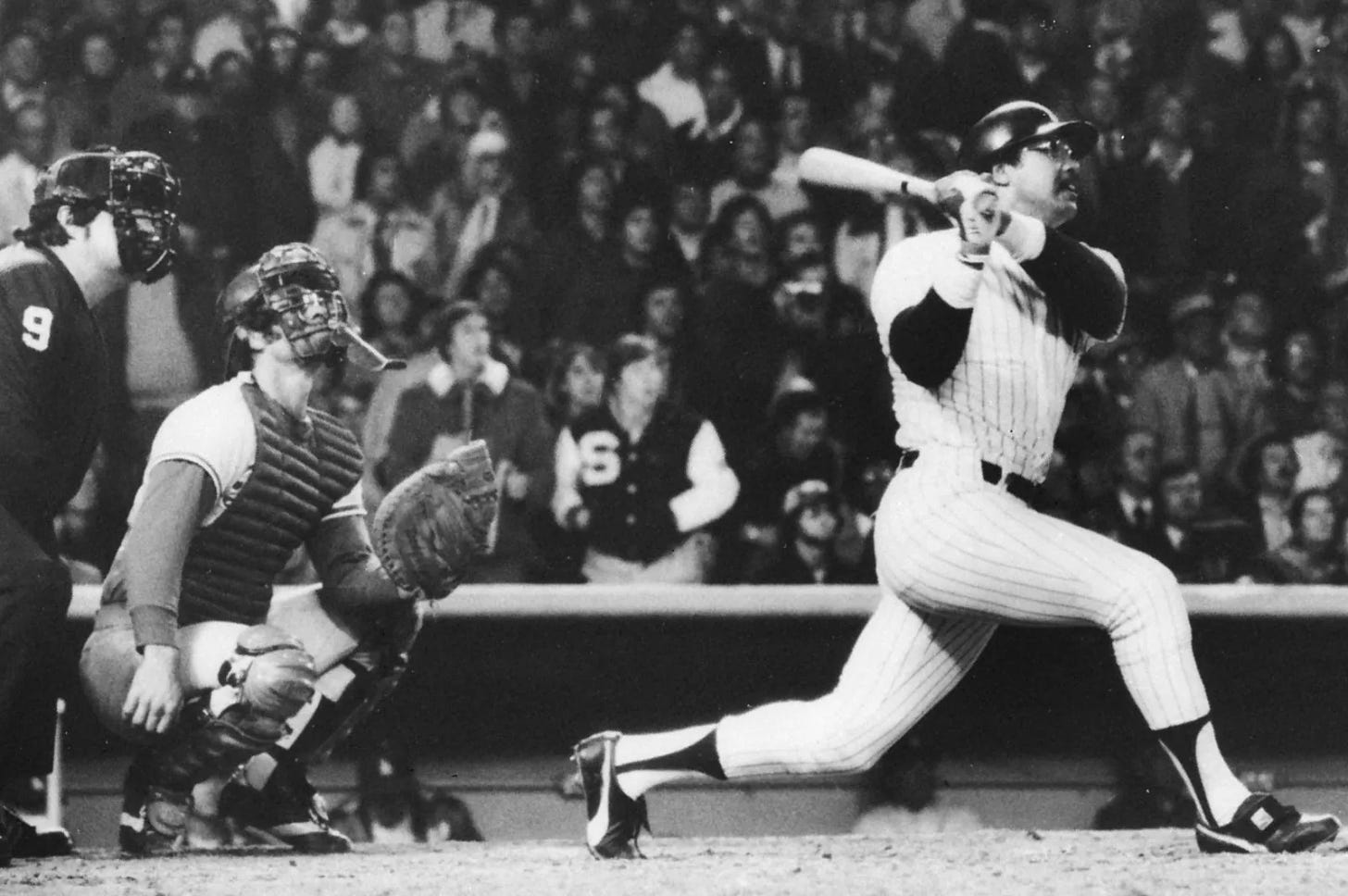

I’ve been thinking a lot about the interview with Reggie Jackson as part of his return to Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, for the Negro Leagues tribute game last Thursday. Jackson joined a panel of former players, including Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, and David Ortiz for a discussion about the history and legacy of the Negro League.

At one point Rodriguez asked Jackson to reflect on what it means to return to Rickwood Field. In 1967, before he joined the majors, Jackson played with the Birmingham A’s in the Double-A Southern League as one of the few Black players on the team.

This wasn’t the first time Jackson reflected on the racism he experienced during his time in Birmingham, but it clearly took the other panelists by surprise and likely much of the viewing public.

I can’t help but think of Jackson’s honest and emotional assessment of his time in Birmingham alongside the news out of Virginia that the Department of Education proposed dozens of changes to the African American History course.

The proposed revisions are an example of how political decisions have the potential to impact classroom content. The documents show that the review offered more than 40 suggestions to the curriculum outline and course content. Many proposed changes focused on language, like changing the term ‘racism’ to ‘discriminatory practices.’ Others were more substantial, like striking a definition of “Black joy” and removing lessons on implicit bias and equity.

Here are a few screenshots from the report:

The contrast between Jackson’s history lesson and the lessons that the state of Virginia doesn’t want students to learn couldn’t be clearer.

Jackson refused to water down the racism that he experienced as a player and he also refused to censor himself, using the N-word more than once.

The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled. Fortunately I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me get through it, but I wouldn’t wish it on anybody. I walked into restaurants and they would point at me and say ‘a n***er can’t eat here.’ I would go to a hotel and they would say, ‘a n***er can’t stay here.’

But as blunt and honest as Jackson was in his response, at no point did he suggest that the day was not worthy of celebration. He never asked viewers to turn the televisions off. Jackson was asked a question and he responded in the only way that he knew how.

Any reasonable person watching must have acknowledged the sincerity of his response as well as the necessity of sharing it with the audience.

Anything less from Jackson would have disgraced the memory of those African-American ball players, who suited up to play America’s favorite pastime and he knew it.

Politicians today are working hard to censor the teaching of American history by taking the sting out of some of the most important historical subjects surrounding the history of race and white supremacy.

But if a baseball legend and great American like Reggie Jackson had to endure the pain and humiliation of racism, as he lived out his dream, our students have the responsibility to understand the long history of why and the ways in which it persists to this day.

Couldn’t agree more about Reggie killing it. A few months ago I watched an autobiographical video on Prime (I think) in which Reggie pulled no punches about his treatment in general and in Birmingham in particular. In April I was traveling solo in Alabama and went to Rickwood Field during their prep for the MLB game. I met the young man, Jabreil Weir who is the groundskeeper and more. He took me around the stadium (it was closed) for a personal tour! He was so knowledgeable and so reverent about the place—“the holy grail of baseball’. He talked about meeting Reggie and other icons in person during his (ongoing) tenure there. I came away from this place (and the Negro Southern League Museum, in town) with a much better understanding of and appreciation for the depth of racism in our recent history as well as the noble resistance against it. Visit Birmingham. There is so much to learn there.

While we're here on this, I've always found it somewhat interesting that the racism early Black players faced is typically confined to the story of Jackie Robinson and all he went through... but no one else. For example, I never heard much of Willie Mays, Roy Campanella, or Willie McCovey dealing with overt racism from fans or other players.

Then several years ago, I read the book "Carrying Jackie's Torch" by Steve Jacobson. It told the stories of the players who came after Robinson and the things they went through. It even included the story of how Ken Griffey, Jr. was subject to racist heckling in the minors. And after the game, the hecklers were waiting for Griffey in the parking lot.

Anyway, as far as Reggie Jackson sharing his story, I can't help but think that all of the men at that desk with him would have heard the same thing had they been there in Birmingham in 1967. They can consider themselves very lucky that they didn't have to deal with that level of racism. But what's interesting today is that there are fans who love some of these Black and Brown players because they play for their teams and do things that win ball games and championships. Yet those fans harbor racist attitudes. An Black individual who performs to my satisfaction is OK, but not Black people as a whole group.