I wrote an entire book about why it took so long for the Confederacy to finally pass legislation authorizing the enlistment of Black men as soldiers. This fact isn’t difficult to appreciate once you understand that the Confederacy’s primary goal was the defense and expansion of chattel slavery throughout the west and eventually to other parts of the western hemisphere.

Confederates defended their “cornerstone” throughout the war. During the debate over the enlistment of slaves as soldiers in early 1865, Major-General Howell Cobb of Georgia wrote to the secretary of war in Richmond:

The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong but they won’t make soldiers.

Cobb could not have been clearer as to the conflict between arming Black men and the purpose of the government that they were then desperately fighting to defend.

While Cobb’s argument was focused on the institution of slavery, he was essentially defended the moral underpinnings of the institution by casting African Americans as suited to their roles as chattel.

The Confederate government approved the enlistment of slaves as soldiers in mid-March 1865, much too late to make any difference to the outcome of the war. They simply could not imagine how to assign Black men to a role that most people believed was appropriate for white men only.

While it may sound strange to say, the United States operated under similar circumstances. The problem wasn’t slavery, though four Border slave states remained in the Union and Lincoln had to do everything he could to maintain their loyalty. That, of course, included refusing to enlist Black men as soldiers in 1861.

But it wasn’t simply the Border states that presented a challenge to such a project. A large percentage of the loyal white citizenry of the United States believed that the war should be fought by white men and the war’s goal should be limited to the preservation of the Union.

Neither side sought to recruit Black men into their respective armies in 1861. The United States and Confederacy followed different trajectories forward, based on a different set of wartime circumstances, but the racial attitudes of their white citizenry overlapped in significant ways.

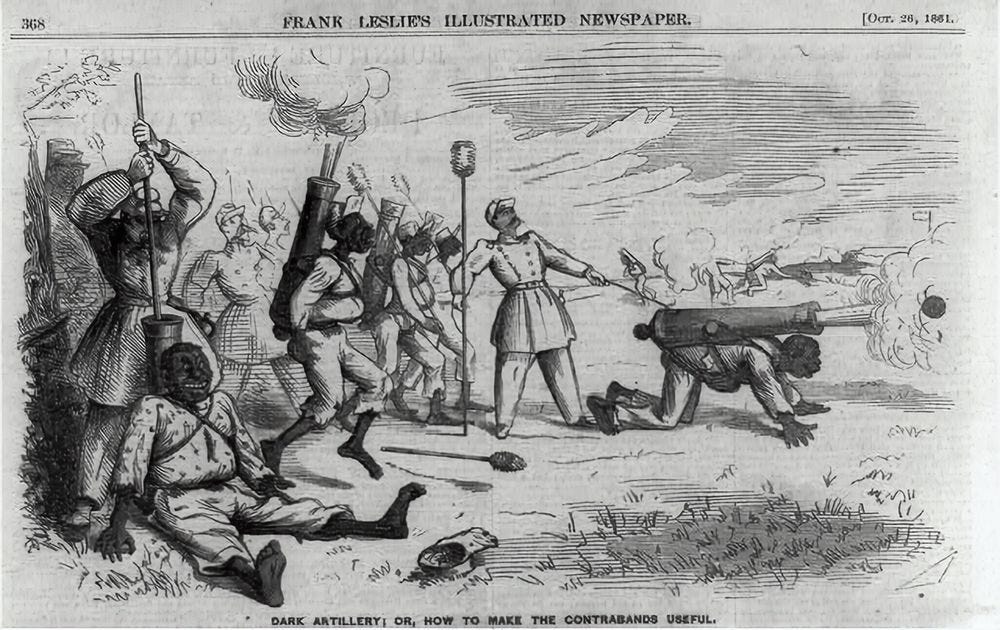

Consider this cartoon that appeared in the popular Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on October 26 1861.

By then, thousands of escaped slaves or freedom seekers had crossed into Union lines forcing the Lincoln administration and Congress to respond. In 1861, the United States began classifying all escaped slaves who had made their way to Union lines as “contrabands”—a murky status somewhere between freedom and slavery.

Frank Leslie highlighted the complexity of the contraband issue and the fact that the Union Army forced African Americans into service as domestic workers, field laborers, and construction workers—reinforcing the continued inferior status of African-Americans.

Of course, African Americans were not yet welcomed into the army as soldiers and this cartoon helps to explain why. While Lincoln had made a political calculation about the impact of opening recruitment to Black Americans, a pervasive racism made it next to impossible for most white Americans to imagine these men in uniform and carrying rifles.

In the coming weeks I am going to make good use of Substack live. The plan is to host one more session for all subscribers and then restrict it to paid subscribers only.

Upcoming sessions:

Books on Civil War military history for beginners (free)

Books on the history of Reconstruction for beginners (paid)

Books on the Black military experience for beginners (paid)

Download the app to take part and make sure to upgrade so you don’t miss a thing.

Leslie’s Black “contraband” capture a spectrum of racist tropes from the mid-nineteenth century, from their exaggerated physical features to their bare feet. Their smiles indicate that they are oblivious to the dangers that surround them. Most telling, they are depicted as disposable in their use as ‘cannon fodder.’

The cartoon offers a window into the limits of the imagination of most white Northerners, who refused or simply could not imagine these men as soldiers. But it also reflects how the war was already changing, in large part owing to the enslaved population itself, which refused to sit by passively. It was the enslaved population that helped to instigate the changes that gradually eroded the institution of slavery in the Confederacy and pushed the United States ever closer to a policy of emancipation.

That was anything but inevitable in 1861 when this particular issue appeared. As I have noted on this site before, the Civil War could have ended with slavery largely intact and without Black military enlistment. That the war didn’t end in a timely manner forced white Northerners to reconsider the enlistment of Black men, even if their racial views lagged woefully behind.

Frank Leslie’s cartoon is a time capsule that reflects both the changes wrought by war during its first year and the continuity of most people’s racial outlook. Looking forward from 1861, we can see the radical change that was just around the corner, which few people could have anticipated.

Slavery was abolished in 1865, but the racism reflected in this cartoon outlasted the war and would return in the twentieth century as African Americans once again sought to fight for the United States in both World War I and World War II.

Can we learn from the past?

Thanks for this post.

What an appalling cartoon, with those cannons. That’s not a complaint or criticism. It’s just a statement about something that in my view is necessary for people to see. It’s appalling, but I’m glad that I now know about it.

And I was glad to see this statement: “It was the enslaved population that helped to instigate the changes that gradually eroded the institution of slavery in the Confederacy and pushed the United States ever closer to a policy of emancipation.”

As I’ve said here before, and elsewhere, my view is that that crucial factor in the political evolution of emancipation is too little recognized.

But nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that Americans will esteem the Civil War‘s multitudes of freedom-striving, emancipation-forcing slavery escapees. Just not yet.

"Can we learn from the past?", Kevin asks.

As a fair number of commentators have said, such as Churchill, America has always done the right thing, but only after it has tried every other alternative!

After reading this column and the comments, this occurs to me as a strong corollary to that quip: "Americans may remember their history, but only after first refusing to learn anything from it."

Kevin: your post is even more fittingly ironic than I realized when I started this comment!

Countless examples stain US military history post-CW: the mistreatment of Pilipinos after The Philippines were taken from Spain. Unsure what-who these new colonials were, American political cartoonists caricaturized "Negro" stereotypes and slurs on them. Despite having been Catholicized by the Spanish for three centuries or so, President McKinley withdrew his pledge to grant them colonists their freedom until further colonization "Christianized" them!

Little need be cited about the faux New Jersian who resegregated the federal civil service and US Navy. Over the next quarter-century, African Americans were again deemed incompetent to serve as warriors (except in Buffalo Soldier cavalry units) until extreme military necessity compelled FDR to authorize the 761st Tank Bttn, the Tuskegee Airmen, and sailors but only if they all were segregated.

My uncle enlisted right after Pearl Harbor and like all Nisei, was shunted into a service battalion until FDR finally liked the idea of a "suicide battalion" of Nisei in 1944. Unc was trained as a medic but not assigned until he got into the new 442, as a rifleman. Issei and other Asians were allowed to serve in the US Navy earlier (my grandfather served on the USS Kearsarge in 1906), but only in roles such as busboys and kitchen help, or like the actor Mako in 'Sand Pebbles', mechanics' assistants. My three uncles who served all got and used their GI Bill benefits. The African American vets who lived in the Deep South were cheated by the Congressmen who prevailed on federal bureaucrats to redline residential zones or simply write these vets as unqualified for the benefits and loans.

Back to Pilipinos, the young men performing West Coast farm labor and factory work weren't allowed to enlist, until 1942 when a regiment of Fil-Am infantry were recruited. It was so immediately oversubscribed that a second regiment was allowed. Congress promised, again, that The Philippines would have both independence as a stalwart American ally but also dual citizenship. Immediately after the war, the nation got its independence (just how much it was to set up the anti-Red defensive screen off the Asian continent, you can guess). Congress reneged on the promised Citizenship and veterans benefits in 1946. (My wife was on Rep Nancy Pelosi's staff in 2009 when Pelosi got veterans benefits for by-then very elderly WW2 vets through Congress, when the GOP wasn't looking. We helped in the effort and were proud to walk with an honor guard when the ceremony in their honor was held here in San Francisco. Memory only took 63 years and a consummate politician who cared!)

One of our acquaintances is Betty Reid Soskin, the 102-year old NPS ranger who retold how she finally was allowed into the war factories; however, she and other Black women were denied factory production line work and relegated to clerical duties. Surprise? racism here, there, now, then, everywhere and every time!

Soskin said she once met a young sailor at a weekly party she and her then-husband hosted for Black sailors at Port Chicago -- that was on the weekend before the nuclear-level detonation of ammo transport ships occurred there. Stories circulated that these sailors were treated by Southern officers as slaves, even holding races to see which ship's laborers could carry their ammo loads faster up the gangplanks and into the holds. 70 years later, Soskin was still bothered by the memory of the young sailor who paid his respects to his hostess, as he had to report to duty at Port Chicago.

Using Black servicemen to race with live ammo in a military port, in July 1944? The 1864 pro-Confederate cartoon showing slaves used as cannon carriages proves that Confederate/Southern memories are entirely and perfectly circular! This brainless and soulless circuit required 80 years. (In 1994 the feds recognized the memory of these sailors with a memorial; "On July 17th, 2024, the Port Chicago 50, along with the 208 men who initially refused to work and were subsequently court-martialed, were officially exonerated by the Secretary of the Navy." (NPS webpage)

Another 80 years. In the local news this summer there was coverage and I think one of those 208 court-martialed sailors was still alive to attend.

Rueful thanks, Kevin !!