There’s a new movie out about what the next civil war might look like. Perhaps you’ve heard about it. I have not seen it and I probably won’t before it drops on Netflix or some other streaming service.

The movie is getting a good deal of attention at a time when many Americans are fearful of increased political division and violence. The movie appears to be doing an effective job of manifesting those fears, though it seems to me that it is just another excuse to blow up iconic monuments and buildings like the Lincoln Memorial and White House.

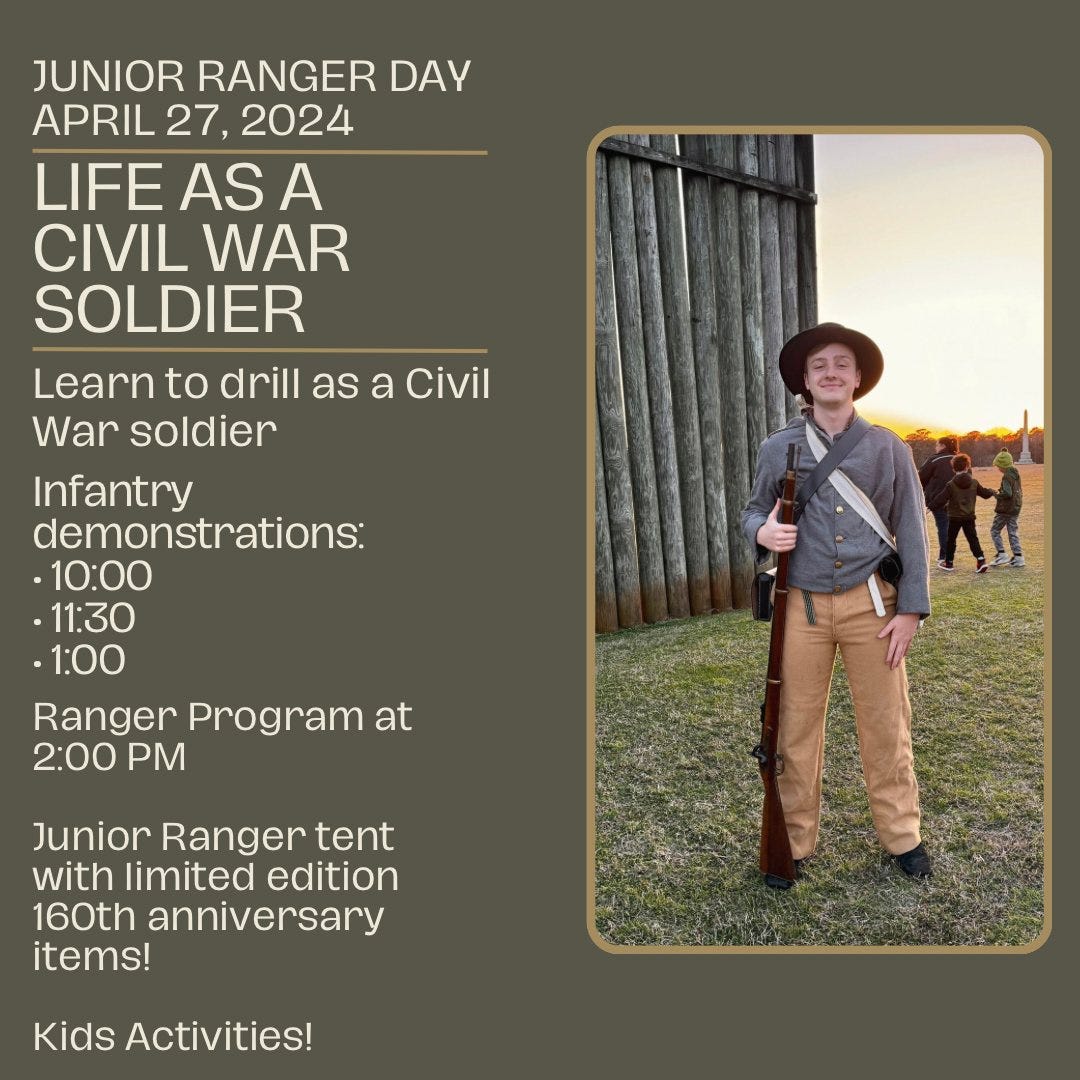

Contrast that with an event planned at Andersonville National Historic Site, where children will have the opportunity to drill as Civil War soldiers. That’s right. The Civil War’s most notorious prison camp, where close to 13,000 Americans died defending this nation and whose commandant was executed for war crimes, wants to give kids a taste of what life was like for Civil War soldiers.

I have a great deal of respect for the work that National Park Service historians and other employees do to maintain and interpret some of our most important historic sites around the country, but this seems highly inappropriate.

A former park ranger at Andersonville posed the following in response:

I can't imagine Manzanar National Historic Site inviting the public to learn how to march like the Army Military Police guarding the internment camp or a generic "World War II soldier." I'd be surprised if Sand Creek National Monument brought kids in to drill like Colorado militiamen. I doubt anyone would rebuild HMS Jersey, where Americans were imprisoned during the Revolutionary War, so that kids could learn about life as a British sailor. And here the U.S. government encourages children to dress up as guards at the deadliest Confederate prison.

I can’t say whether children will actually be wearing Confederate uniforms, but that’s not really the point here. Union soldiers didn’t drill at Andersonville. They starved. They fell victim to disease. They died.

There is nothing wrong with holding an event to teach the public about the life of the Civil War soldier, but context and place matter. Perhaps this program will reenact Union soldiers, who ‘crossed the line only’ to be shot by Confederate guards.

This is certainly not the worst thing that can happen at a historic site, even at a place like Andersonville. The employees certainly didn’t intend to be insensitive. In fact, I suspect that they would be hard pressed to even explain why someone would take issue with this program.

That said, I can’t help but contrast the public conversation surrounding the movie Civil War, the insistence that it be taken seriously and with all the violence that it portends and our long history of overlooking or making light of the violence of our real civil war.

We don’t need a Hollywood movie to dramatize the dangers and brutal violence of a possible civil war. We could just look more closely and honestly at the one we actually fought not too long ago.

My friend and fellow historian Evan Kutzler once worked at Andersonville as a park ranger. I quoted him in the post. He just posted this piece, which he wrote five years ago. It turns out that this event will fall on the anniversary of the first Decoration Day at Andersonville in 1869:

Government "shutdowns," of various kinds, hurt people and some of the suffering at Andersonville in 1868 and 1869 was the product of laying off federal employees. It was also a factor—among many—leading to the first Decoration Day at Andersonville in 1869.

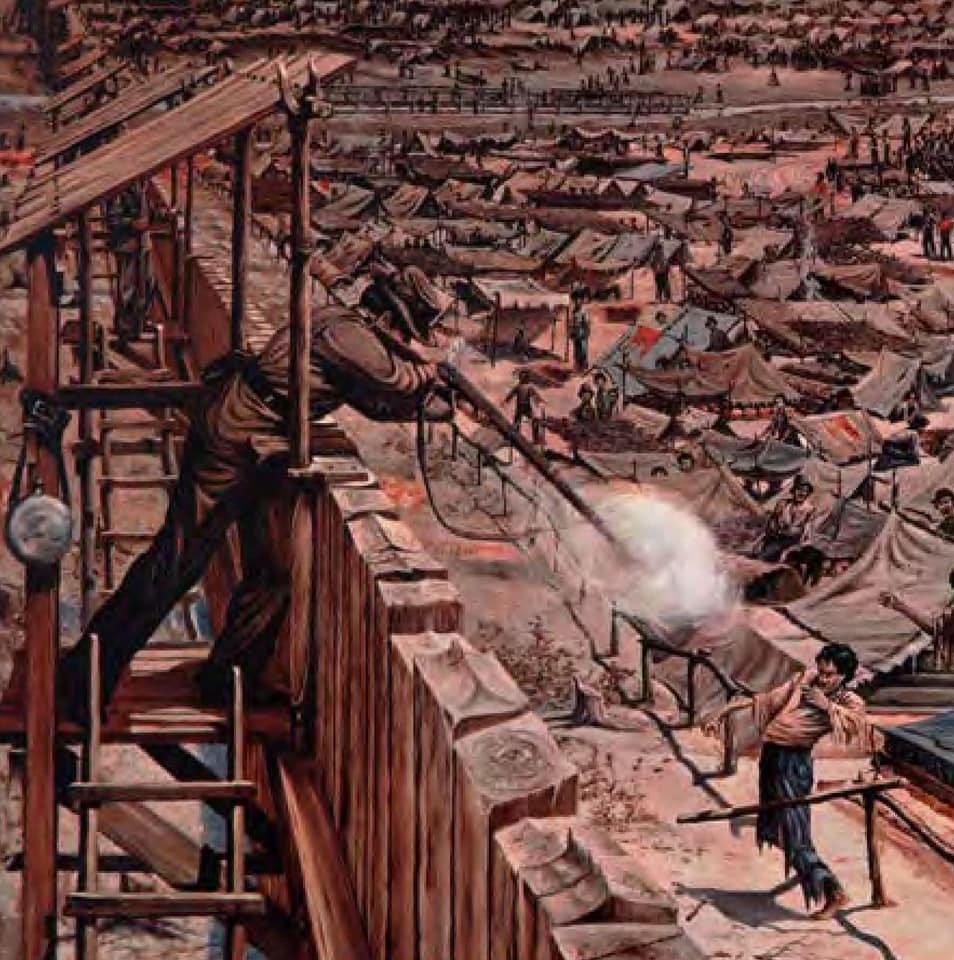

At the beginning of 1868, two hundred freedpeople lived at Andersonville and were engaged in landscaping a new Andersonville National Cemetery that never saw use. These monthly government jobs paid lower than local contracts negotiated by the Freedman's Bureau, but working at Andersonville had its benefits: it was not plantation work; there was a school nearby; and since summer 1865, it had been a safe place for families. However, the new cemetery plan went against government instructions to minimize costs and, when the Quartermaster General discovered its scale and cost, most of these laborers lost their jobs. Most chose to stay at Andersonville anyway.

Violence was never far off. The freedpeople at Andersonville participated in peaceful elections in November 1867 and April 1868, but that July white county authorities sanctioned—and participated in—a raid that evicted scores of men, women, and children from their homes at gunpoint. Those who remained or returned took caution, armed themselves, and posted sentries to ward off night raids by disguised men on horseback. Despite threats of being fired, the remaining cemetery workers organized a "Grant Club" and that September marched through the streets of the Andersonville town. Making good on his threat, the cemetery superintendent, a Democrat, fired them but then rehired them later that afternoon. The workers got revenge in 1869 when they reported that the superintendent had been illegally renting out government mules. All in all, the Andersonville march in September 1868 could have been much worse. In Camilla, at the southern end of the same congressional district, marchers protested the ousting of twenty-eight black representatives from the Georgia State assembly. White men shot dozens down. Still, things were getting worse at Andersonville. Elections that November were a mess. At the beginning of 1869, the Ku Klux Klan drove off a northern minister with a death threat. It remained a dangerous time.

It was with this recent experience that black students at Sumter School, preparing for spring examination exercises, learned that white Georgians were planning to decorate the graves of Confederate guards on Tuesday, April 27, 1869. These rebel graves were adjacent to Union graves and on the other side of a small wooden fence. Students reached the cemetery at 7:30 a.m., approximately twenty minutes before sunrise in an era before Daylight Savings. Preempting the Confederate mourners, students spreads oak leaves and flowers on the 13,000 Union graves and the graves of Confederate guards. “The ladies and gentlemen who came during the day from Macon and Americus covered their soldiers’ graves with beautiful bouquets,” a northern teacher wrote, “but had none for the martyred sons of the Union.”

Decoration Days were much bigger in the following years and involved thousands of people making their way to Andersonville. Yet the first Decoration Day at Andersonville stands out because it was performed after a year of firings, protests, threats and violence. It was also an act that could be interpreted in several ways. Was it an act of forgiveness? Was it an assertion of moral superiority? Was it a continuation of subtle subversion perfected under slavery but still applicable in the violence and recent backsliding of Reconstruction? Perhaps it meant different things to the forty-five or so students who participated.

Bravo for calling out this grotesque perversion of what can actually be an honorable method of sharing and building Civil War memory: reenactments. I've never beeen to one, but I'm a close correspondent on Civil War memory matters with Erik Curren, a scholarly impersonator of General Grant. Erik has a Ph.D. in English and, as I say, he brings scholarly scrupulousness to his portrayal.

https://usgrant200.com/historic-interpreters/erik-curren/

(As to that movie, if I'm correctly informed, it doesn't bother with attempting, in fiction, to base itself on any coherent political grounding. It just seeks to inflict a random sense of horror. Well, there's a certain category of American that might include some who need to see the movie to motivate them to think twice. I'm talking about swaggering, goofball special-ops wannabes in their special-ops costumes and with their big ol' intimidating war weaponry. But maybe their number is now actually small, with many of them already in jail because of their 1/6 betrayals of America. And maybe most of the rest will recognize that they have a nice couch, a nice TV, and a nice fridge with beer in it, and will just stop the violence-threatening self-beclowning.)