Placing the Question of 'Why They Fought?' in Perspective

When exploring the question of what the United States was fighting for in Vietnam, we don’t get bogged down in the question of what motivated individual soldiers. Most people acknowledge that the majority didn’t volunteer at all, but were drafted to fight in a war against Communism.

The same holds for our understanding of WWII. The United States was fighting fascism in Europe and Japanese imperial ambitions in the Pacific. Countless numbers of books have shed light on the experience of the private soldier, but even here we don’t allow the motivation of any individual soldier(s) to steer us away from the stated goals of the United States government beginning in 1941.

The Civil War is the exception to this rule. For some reason, our understanding of the goals of the Confederate States of American and United States are inextricably bound up in the question of why soldiers fought. This bottom-up approach represents a failure to fundamentally understand the relationship between the military and the governments for which they were attached.

How many times have you had to listen to someone argue that because their ancestor didn’t own any slaves the Confederacy was therefore not fighting to defend it or that because most United States soldiers never expressed abolitionist principles that therefore emancipation and ultimately the end of slavery had not emerged as a crucial wartime goal by 1863?

It’s maddening.

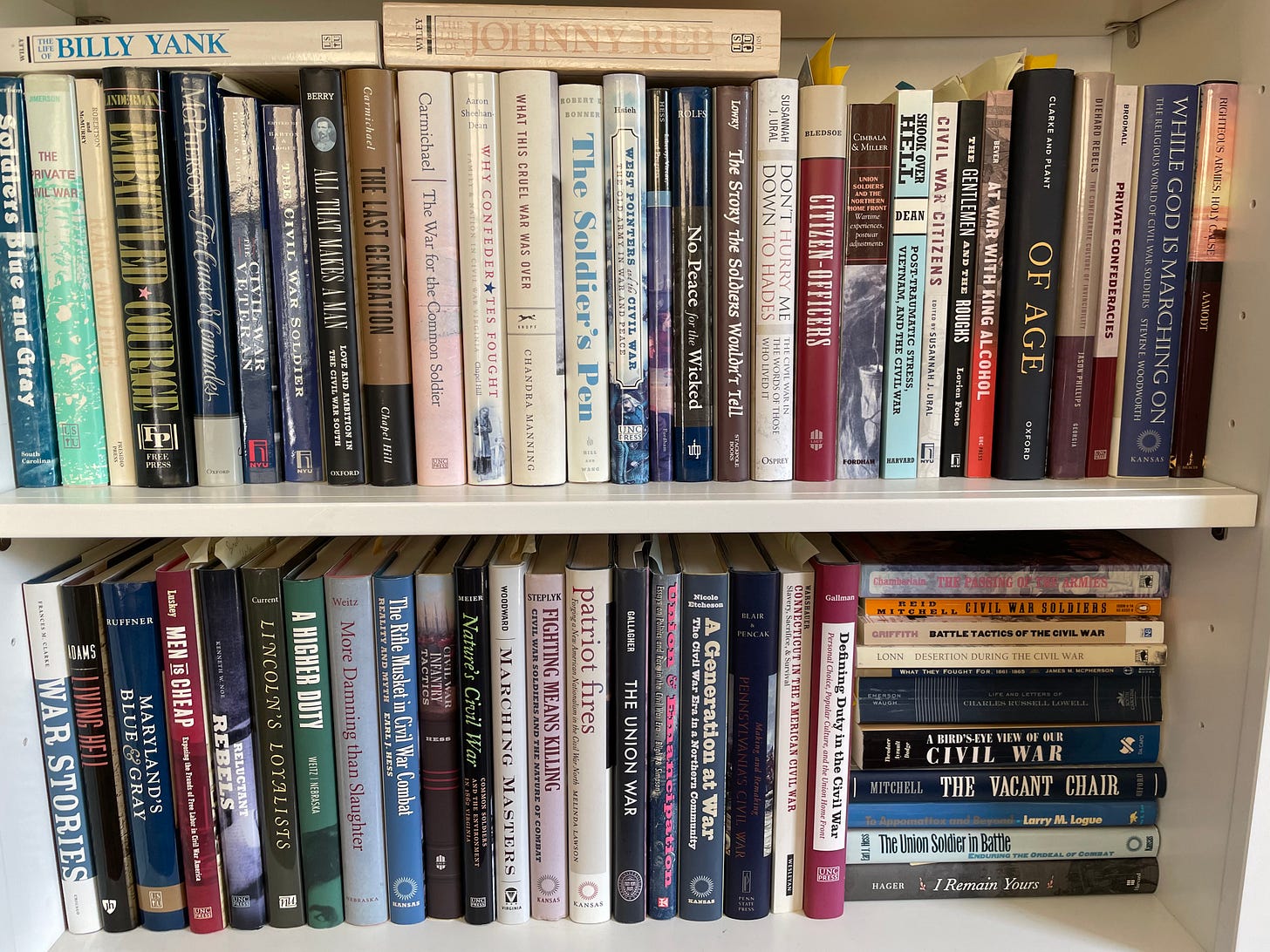

We have a deep body of scholarship on Civil War soldiers going all the way back to Bell Wiley’s probing studies of Johnny Reb and Billy Yank. The scholarship has become even more sophisticated in recent decades owing to the types of questions asked and the emergence of new evidence.

More than three million Americans fought in the Civil War. Their experiences and stories matter.

The political goals of both the Confederacy and the United States were both influenced by its respective civilian populations through the pressures that they exerted on their governments. Citizen soldiers on both sides, who retained a deep independent streak, also made their voices heard in various ways through volunteering, reenlisting, and deserting the ranks.

Many more were conscripted, beginning in the Confederacy beginning in April 1862, followed by the United States the following year.

The wartime goals of both nations were formulated and evolved in response to military affairs, but they were not dependent on the question of why men fought any more than they were during WWII and Vietnam.

Regardless of whether a Confederate soldier owned slaves, he was fighting for a government that expressed, over the course of the war, its commitment to slavery.

As I have suggested before, the question of slave ownership is a distraction from the more important question of whether these men understood the importance of enslaved labor to the military’s success. And if you acknowledge the thousands of enslaved men that were forced to accompany Confederate armies throughout the war, I don’t think there is any question that the rank and file acknowledged its importance.

The same holds true for the United States. Regardless of a soldier’s view of enslaved people and slavery, after 1863 he was fighting in any army that was tasked with carrying out the government’s policy as stated in the Emancipation Proclamation. Many would soon be fighting alongside some of the roughly 200,000 Black Americans who volunteered to fight by the middle of the war.

As historian Allen Guelzo puts it in his new book about Gettysburg: “The Army of the Potomac was not necessarily the slaves’ best friends, but it was definitely slavery’s worst enemy.”

Most Northern soldiers many not have initially been motivated by a desire to end slavery, but by the middle of the war many had come to acknowledge that destroying it would bring the war to a speedier close and their union intact.

But even with all that said, we must resist reducing Civil War soldiers to the question of slavery with the conversation beginning and ending around which side they fought for. Doing so reduces these men to caricatures, but more problematic is that we end up using them for our own purposes that almost always have little to do with historical understanding and everything to do with current politics and the culture wars.

Let’s study the lives of Civil War soldiers, but let’s not confuse their experiences with what we know was at stake in this war.

As I told my US and the World Wars class, "You know what you call someone who joined the NAZI Party not because they hated Jews, but because they wanted to make their friends happy, or for career advancement, or because their friends did? You call them NAZIS. No one f'ing cares WHY they did it." If you fight for an evil cause, you get painted by the same brush as the true believers. Saying you didn't REALLY mean it doesn't remove the stain.

I know. Subtle as a ton of bricks. But sometimes a little moral clarity is needed.

Have you read Anne Marshall's "Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State"? She talks about the effect of the Emancipation Proclamation on support for the Union in Kentucky as many hoped to both preserve the Union AND preserve slavery.

I also hate the "my great-great Grandpa didn't own slaves, so he didn't fight for slavery" BS. I am pretty sure that if you asked those enslaved at the time, they would not appreciate the distinction.